Winter hazards in some areas don’t peak until around Valentine’s Day, and could last a couple more months before ceilings, winds, and cold start letting up. So, those accustomed to the season take more care planning their trips, accepting more risk of cancelling them. And when a flight does depart, that preparation surely gets put to the test.

Yeah, It’s Cold

Flying from southern Ohio to Selinsgrove, Pennsylvania, in February wasn’t your first choice for a 300-mile cross country, but family obligations required an early-afternoon departure for the two-hour flight. That gets you to KSEG well before sunset, but the northeast headwinds added some extra time pressure. Plus, winds are gusting up to 35 knots at the surface.

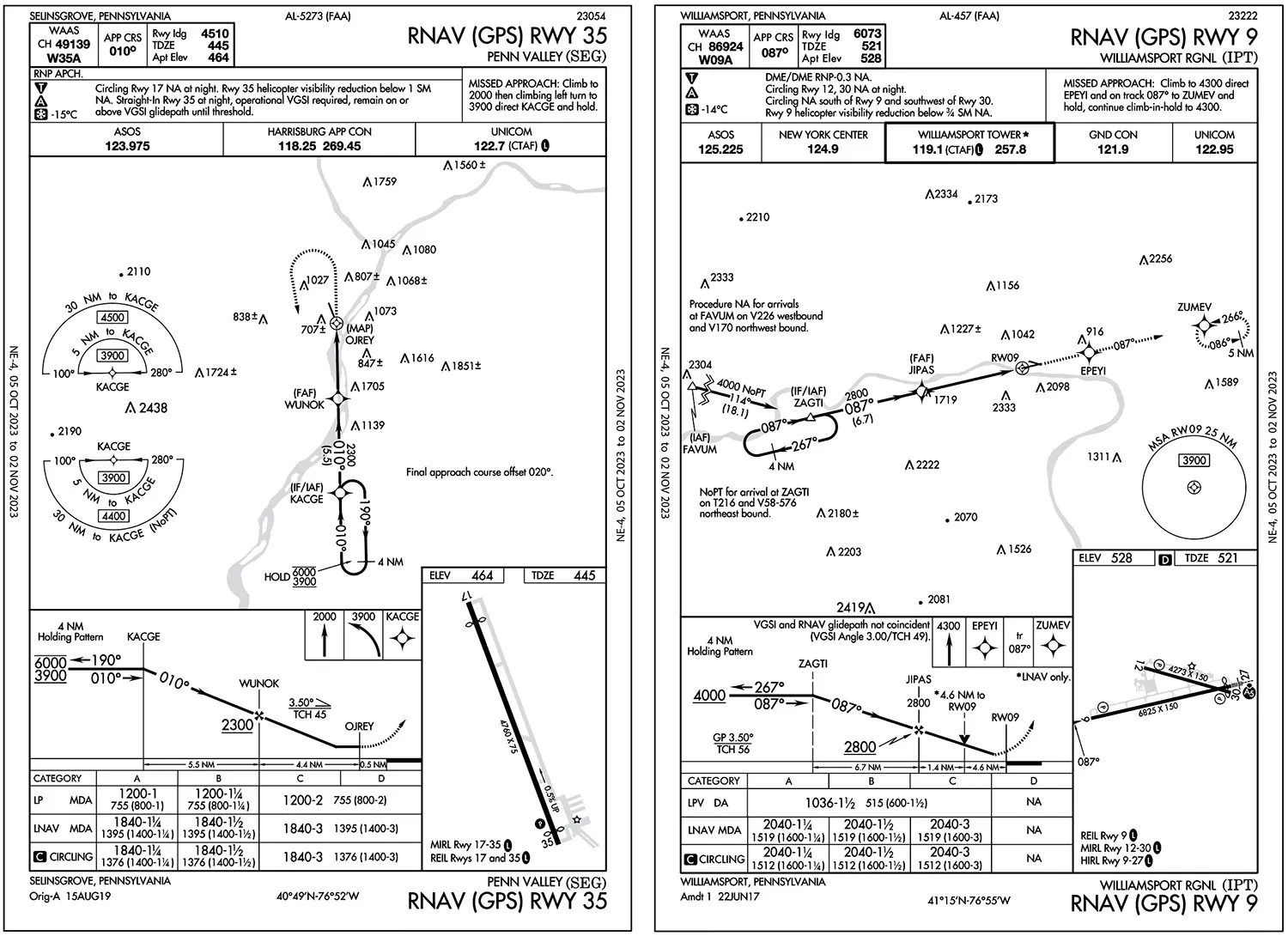

The RNAV 35 at KSEG is just within your limits so long as winds don’t swing further east. If they do, there’s an alternate with an RNAV 9 approach at Williamsport, where the latest winds were northeast at 25 knots. Someone can fetch you there in about an hour. Both destination and alternate, then, have LNAV minimums for your 10-year-old IFR panel. You’ve been happy with the equipment, sticking to flights when ceilings are at least 1200 feet.

You’ve had lots of wind and crosswind experience this year, but nothing exceeding 30 knots. Will another five make a difference today? Well, that’s what alternates are for. Williamsport also has much better ceilings at 2000 feet, compared to Selinsgrove at 1500. You quickly bookmarked the RNAV approach charts with plans to review them in flight so you can spend the time before departure ensuring there’s no big weather change coming, and no icing reports enroute. With forecasts for scattered layers between 1000 and 5000 feet, you need escape routes in case you encounter unexpected ice.

At cruise above the turbulence, the RNAV 35 chart shows a typical hold-in-lieu of procedure turn (HILPT) at the IAF, which you don’t expect to use given your inbound course. The approach has Category A LNAV minimums of 1840-1¼. And the displaced threshold reducing landing length to 4510 feet isn’t an issue, but worth noting for a gusty approach requiring extra airspeed and runway and, in your judgment, partial rather than full landing flaps.

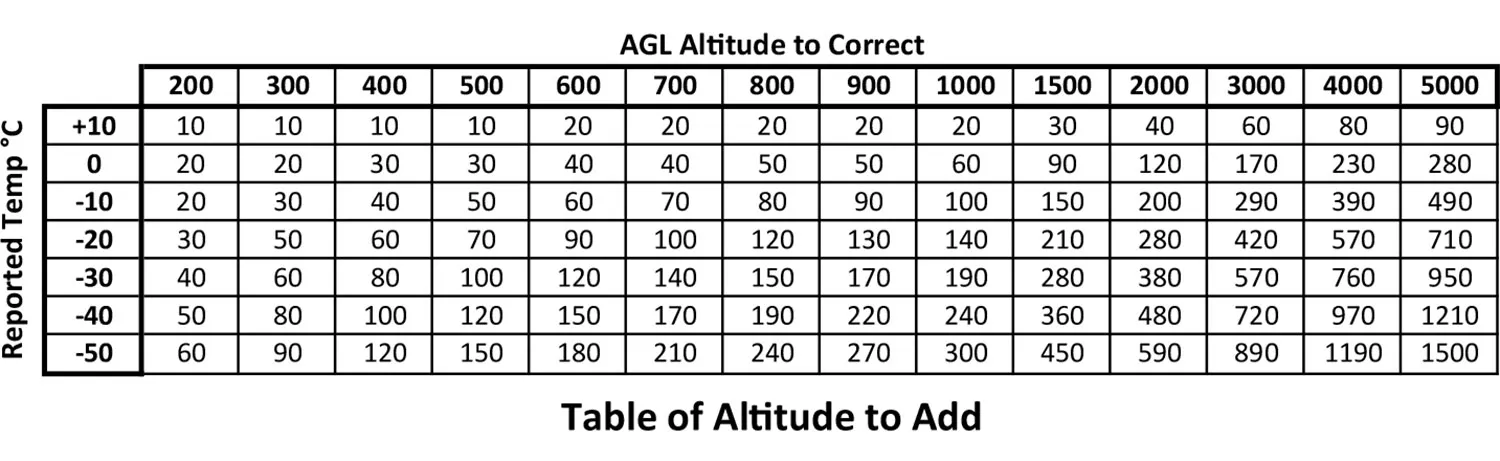

There’s also the snowflake symbol in the notes box for -15 degrees C. This is easily accomplished in a nice warm hangar with good Wi-Fi and a calculator, but not so easy if you’ve never done it and you’re trying to find this thing called a Cold Temperature Error Table and its instructions. And you might not need to correct the entire procedure; there’s a table for that too. But where?

It took the entire half-hour before descent to dig these up from the endless files saved on your EFB. Selinsgrove is -20° C now, and the approach requires correction at -15. That’s cold enough to risk terrain proximity—hence the snowflake. Now, quickly brief the approach altitudes: 3900 for initial, 2300 feet to the final, LNAV MDA 1840 feet (about 1400 feet AGL). Corrections apply to the final segment at Selinsgrove and the alternate, so you add 196 feet to 1840 feet and round to a comfy 2100-foot MDA.

Surprise Hold

But there’s the “by the way” planview note: “Final approach course offset 20˚.” For the offset approach course, you’ll need to think about this in case something won’t work. You see that it’s far more than the usual five to seven degrees for many straight-ins. The inbound course is 010 degrees to Runway 35.

A quick check of the official data shows that the runway magnetic course is indeed 350 degrees, for the stated difference of 20 degrees from final. And winds between 1000 and 3000 feet are even stronger—40 knots from the right on final; this’ll have you pointing the aircraft even more off the runway centerline, maybe up to 30 degrees or so.

This still didn’t nudge you into diverting. But upon clearance for the approach and heading to KACGE, the winds and associated turbulence were worse than expected. But focusing on the offset kept you too busy to think of the what-ifs.

While you were only one dot off to the west of course, getting back on with the headwind/crosswind took until OJREY, the 0.5-mile final. With the large drift-correction angle and just seconds to swing the nose to align with the runway, you were still 50 feet above the (corrected) MDA crossing the displaced threshold, and now the 4500-foot landing length suddenly looked too tight.

The subsequent go-around was fine, but since you were busy managing winds and bumps, you didn’t notify ATC until back at KACGE for the hold. The massive crab-angle—now to the left—required both hands. If you hadn’t flown a hold in such a gale before, this would have been a problem staying on course for sure, but you had been in a similar situation in the spring. Yeah, it was a while ago, but you remember it clearly. A sympathetic controller, meanwhile, kept an eye on you while waiting for a reply on the radio. After all, nobody else was waiting to get into (or out of) Selinsgrove. You request a few minutes to decide what to do.

No Seconds

The hold at KACGE required two other adjustments: Powering down and slowing down; your groundspeed in the tailwind and subsequent turns would surely result in a wind-blown slide an extra mile outside the hold unless you reduced speed and anticipated an aggressive crab angle (still at standard-rate turns, of course). This means accepting a big undershoot in the parallel entry along with a southeast crab angle. It’ll be awkward, but better to err within the hold than outside as you turn left back to the fix. Finally, after getting the workload under control, you check the winds, which are now 030 degrees at 32 knots. Williamsport it is.

At least fuel isn’t going to fray more nerves. Since you’d topped off, there’s enough fuel on board for the two-hour flight, two approaches at Selinsgrove, and a couple approaches at Williamsport before tapping into an hour reserve (exceeding §91.167). So instead of fretting about fuel or weather, you can stay focused on flying in the tough winds, this time landing from the RNAV 9 at KIPT with a mere 30-degree crosswind that had eased at Williamsport to 24 knots. With a course of 328 degrees (not including an additional crab angle to the northeast) from the hold at KACGE to ZAGTI, and an inbound course of 87 degrees, you get nice easy vectors to position southwest of ZAGTI.

There’s another cold-temperature adjustment for -14° C, which you calculated on the way. As the lowest scattered layer is now 1900 feet, it was fine to round up everything—the field elevation (500 feet) and DA correction (280 feet) while using the -20° C temperature line to avoid the task of interpolating in moderate turbulence.

This wasn’t the best day to fly, but given the unexpected mission, the high-ceiling, ice-free conditions did keep you from attempting to take on multiple hazards during an approach to minimums. And the crosswind landings would’ve been aborted for sure were it not for your recent experience. It was one of a few things you were able to fall back on when conditions did push you to personal limits.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin, where every degree below freezing raises minimums for IFR flight, including the number of extra coats and mittens required on board.