This sim challenge is inspired by our good friends over at PilotEdge. PilotEdge provides live ATC services for flight simulation. You will be on your simulator, but a real human controller vectors you through virtual airspace with the correct phraseology and skill. There’s no pause button and no spawuming your aircraft on 10-mile final. You start cold and dark on the ramp and need to use the radios to get a clearance, permission to taxi, and so on. It adds a significant element of realism and authenticity to your simulated flight.

PilotEdge has its own set of IFR challenges for pilots. IFR challenge number 10 (a.k.a. “I-10”) is the one most failed—and that’s what you’ll fly today. Get your circling hat on because there’s not a straight-in minimum to be had. Not that you can’t land straight-in … if you play it right. (That’s a hint.)

Flying Down the I-10

Interstate 10 starts in Los Angeles, but you’ll start this I-10 a bit further west at Santa Barbara Municipal (KSBA). Put down your retro wheatgrass espresso-infused smoothie and set the weather for a light southerly wind and ceilings of a reasonable overcast at 1300 feet MSL.

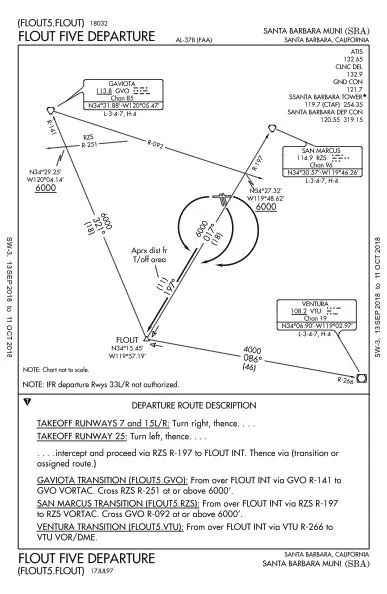

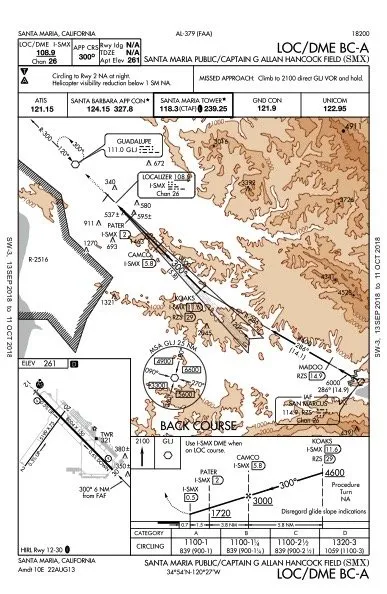

Start cold-and-dark on the ramp to get your head in the game. Then taxi out for the Flout Five departure with the San Marcus (RZS) transition. RZS is the IAF for the LOC/DME BC-A approach into Santa Maria (KSMX), your first stop on this two-leg ordeal. Fly the approach with whatever tools your sim offers, and you chose to employ. Most sims have DME, but many aircraft no longer do. Consider using the sim GPS in lieu of DME for a more real-world experience. Fly the approach to a touch-and-go, or at least try.

After attempting to smack the runway at KSMX, fly the published missed to the Guadalupe VOR (GLI). Once you get there, take at least one spin in the hold while you negotiate a clearance to the San Luis Obispo airport (KSBP). Take as many additional turns in the hold as you need to climb. After reaching 6000, depart the hold heading 360 to join V27 northwestbound toward San Louis Obispo.

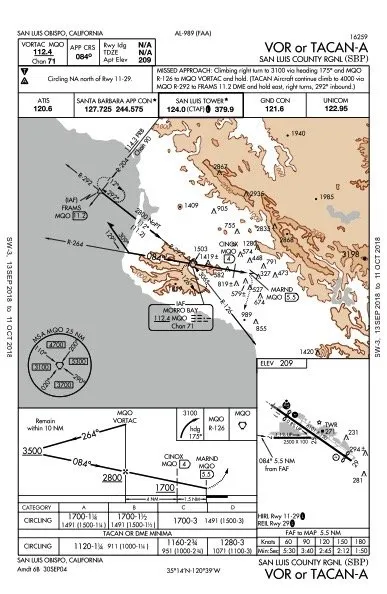

Assume it’s a slow day for ATC, and as you cross FABEG you hear, “… cleared VOR Alpha approach San Luis Obispo.” No, you’re not getting any vectors. So, you have to fly the full approach with the procedure turn and land at KSBP. It should go without saying that you can’t break any rules along the way, just like in real life. If your attempt to get down and land doesn’t quite work out the first time, fly the published missed back to the VOR and try it again … and again, if necessary. Practice makes perfect.

Taxi to parking and shut down before enjoying the view of the mountainside poking up into the cloud deck.

More Route Detail

Of course, the exact clearance you’ll get if you’re using PilotEdge will vary with conditions and traffic at the time you’re flying, but in general you can count on the routing as shown on the facing page. Let’s walk through what those charts show.

You’ll depart Santa Barbara on the Flout Five Departure, San Marcus transition. Approaching San Marcus you’ll get cleared for the approach. (RZS as an IAF isn’t shown on the charts to the right to reduce clutter and connect the charts.)

After your miss from Santa Maria (KSMX) and hold at GJI, you’ll head north to intercept V27 a bit before FABEG. (Airway V27 isn’t accurate on these depicted charts—we had to take some liberties to show it all on one page.)

At FABEG you get your clearance for the approach to San Luis (KSBP). See how that works out for you. After you land, we can debrief using the questions below. See our shot at the answers to this scenario on the next page.

Enhanced Simulation

PilotEdge is a subscription-based service that connects flight simulators to the PilotEdge voice and data network. Information about aircraft type, position, altitude, attitude and heading is sent to PilotEdge’s servers from each simulator connected to the service. It is then relayed to other connected simulators “flying” nearby. Information from the connected simulators is also sent to PilotEdge Air Traffic Controllers on displays identical to those used in ATC facilities. Controllers issue instructions to pilots “flying” in their sector just as they would in the real world.

Flight simulators have long had the capability to create “multiplayer sessions” and allow pilots to see each other in a virtual sky. PilotEdge has added controllers to these peer-to-peer server-based sessions to create an environment closely resembling real-world flight.

PilotEdge ATC services are available only within the Seattle, Oakland, Los Angeles, Salt Lake City and Albuquerque ARTCCs. A detailed coverage map is available on their web site.

PilotEdge supports IFR and VFR operations, including flight following. They also support operations on the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) at non-towered airports. Their voice system is designed to mirror real-world VHF operations. This means that if you launch your IFR flight from some non-towered airports you might need to pick up your clearance after you are airborne. And are able to reach the clearance-delivery facility.

PilotEdge guarantees ATC presence during the network’s published hours of operation. Their controllers are not volunteers but paid employees. PilotEdge also advertises adherence to a rigorous Quality Assurance program to assure ATC quality.

To use PilotEdge you need compatible flight simulation software—generally Microsoft Flight Sim, Prepar3d, or X-Plane; details are on their website—a broadband internet connection and a headset. Of course you need to subscribe to their service and install their client software on your simulator.

IFR Magazine has no connection to PilotEdge. We just think it improves your flight simulation experience and want to let you know.

Questioning Yourself

1. What route and altitude would you file for the leg KSBA to KSMX? How would you file if you wanted the Flout 5 departure with the San Marcos transition? What if you didn’t want any published departure routings?

2. When did you turn to intercept the course outbound to Flout?

3. How did you reverse course at FLOUT?

4. When did you start turning outbound to R-286 at San Marcos?

5. If ATC told you to “hold at KOAKS as published,” how would you hold?

6. Did you make it down to the runway at KSMX? Did you hold that localizer to a dot deflection or less?

7. How did you determine the MAP for the BC approach?

8. How high did you climb on the missed approach from KSMX?

9. When did you leave 6000 on V27 for your approach into KSBP?

10. How did you fly the procedure turn after crossing MQO?

11. How could you fly this approach with GPS?

12. Did you make it to MDA in time?

13. Which way did you land?

14. If you flew the published miss at KSBP, how high were you when you started the second attempt for the approach?

Like some of you, Jeff Van West didn’t quite get this one right on his first try. He persisted though, eventually got it, and now wants share it so you can “enjoy” it too.

DEBRIEFING POINTS

1. First, check for a Tower Enroute Control (TEC) route. This is often overlooked for flights that never leave TRACON airspace. A TEC route would contain both the route and altitudes. You might find a “canned” routing between these airports for piston traffic at a set altitude. The route has a code you can file as your route rather than entering all the fixes. The FAA website iswww.fly.faa.gov/rmt/coded_departure_routes.jsp. As it turns out, there is none for this route, so you’d file “FLOUT5.RZS” as RZS is an IAF for your destination. You could put “No SID” in your remarks, but you’d quite possibly get the equivalent of the Flout 5 as detailed instructions anyway. Better file at or above 6000 feet, since that’s the minimum.

2. Departures are predicated on crossing the departure end of the runway above 35 feet AGL and maintaining runway heading to 400 AGL. If the airport is nontowered, you’d start your turn above 413 feet MSL. In the real world (or PilotEdge), you’d maintain runway heading until turned by ATC.

3. There’s no official guidance on something like this as far as we know, which leaves you to make the 180-degree course reversal as you see fit. We’d probably just fly a teardrop with a tailwind on the outbound as much as practical. So that’d be a right turn to about 227 degrees before a left turn to 047 to intercept R-197 inbound to RZS (a course of 017).

4. It probably depended on how you were navigating. With traditional VORs, you’d wait until full needle reversal and then turn left. With the south wind, that’s a long swing off course. Kinda sketchy considering the terrain in that direction. GPS leads turns. It’s a gray area, regulations wise, but we’d lead that turn no matter how we were navigating.

5. You’d do it in a state of shock, because no one holds en route these days. But if ATC asked, you’d have to reference the en-route chart to find the published hold. No one bothered to add it to the approach chart. It’s standard right turns, but on what inbound course? You’d think 286, the course to KOAKS. However, the hold looks aligned more northerly, but not quite the 307 of V27. Answer: You hold 300 inbound, which is the localizer back course. Jepp enroute charts are kind enough to add that notation to the hold itself.

6. Back course approaches are reciprocals of localizer approaches, which almost always align with a runway. When a BC approach offers only circling minimums that’s a clue there’s an issue preventing the straight-in mins. It might be lights or markings, but more likely it’s a steep descent to MDA. You have 5.2 miles to drop 1900 feet, or 358 feet per mile. Using 300 feet per mile for three degrees, that’s about a not-too-excessive 3.6-degree descent to reach MDA at the MAP. With that south wind, it’ll feel steeper. The localizer beam width is set so approach to the other runway is about 700 feet wide at that threshold. That means the backcourse has a much narrower beam. The longer the runway, the narrower (seemingly more sensitive) the localizer is.

7. DME is in the title, and this is why. There’s no published timing so you better have DME reading from the localizer or a GPS distance from I-SMX. The MAP is 0.5 NM from I-SMX, which is 0.2 from the runway. Note: there are BC approaches where the MAP is a distance from the antenna after you cross it. Watch out for those.

8. Did that get you? It got us the first time we flew it. Given the proximity of mountains and how high you start this approach, 2100 MSL comes up really fast on a busy missed. Note to self: Always brief that level-off altitude on the missed. This is no airspace to be busting an altitude.

9. An approach clearance without a crossing restriction gives you pilot’s discretion from your current altitude down to the MEA for the remainder of your route, including the airway. Once you have the clearance for the approach, you can leave 6000 for the MEA of 4000 on V27. You’d have to cross the VOR at or above 4000, but then could descend to 3500 until inbound and 2800 until crossing the VOR again for final approach.

10. The right answer is, “Any damn way I wanted to.” It’s just a procedure turn barb with no fix shown. You could cross the VOR and pull a fast 80-degree right turn followed by a 260-degree left while simultaneously losing 1200 feet (4000-2800). With a south wind and a full mug of bravado, that might work.

11. It’s legal to substitute GPS for primary guidance on VOR approaches now. Ideally, you’d have the approach in the database, but you could also use OBS mode or GPS direct to the VOR on a course of 084. Be sure you see distance to the VOR waypoint because you’ll need it for the MAP—counting up—of 5.5 NM.

12. This approach looks like an easy descent of about 1700 feet in 5.5 miles, or about 309 feet per mile—very close to a normal three-degree slope. But you can’t descend past 1700 MSL until 1.5 miles before the MAP. That makes the last bit 387 feet per mile, or about 3.9 degrees. That’s steep—especially if you’re not supposed to cross the field and circle on the north side of Runways 11-29.

13. Building on that answer above, you’re technically circling to land, and with a south wind, your best bet is Runway 11—which is a hellava left turn from the MAP if circling north of Runway 11 is NA. Yet here’s the catch: The FAA has made it clear you must fly the correct pattern position when circling to land, and Runway 11 is left traffic. So … can you land Runway 11 at all? We’d argue you could if Tower told you to enter left downwind for Runway 11. If the field was uncontrolled you’d have to ensure you run over the FAA inspector on your way to the ramp—just to be safe.

14. Between 3100 and 3500? It’s a bit of a TERPS anomaly that the hold on R-126 is at 3100, but the course reversal on R-264 is 3500 outbound and 2800 inbound. Real world, we’d probably just fly 3100 outbound and keep it in tight unless ATC demanded otherwise.

Item number 11 referencing use of GPS on a VOR approach, your answer is either not complete or is factually incorrect. The AIM states that GPS can be used BUT the underlying VOR must be monitored for lateral guidance from the FAF to the MAP. So, you’re tracking the GPS and you’re dead on but the VOR CDI shows divergence. What now Kimosabe?

#6. You said It might be lights or markings. I don’t believe lights are required except at night.

Also when deciding whether the final approach is too steep it is 400 fnm from the FAF altitude to the threshold crossing height. but I can’t find it in TERPS or AIM