Change is certainly a constant in aviation. Beyond aircraft technological advances, the rules that govern how air traffic control handles those aircraft are also frequently adjusted.

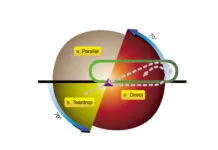

One area in particular that’s seen significant discussion and change in the past three years is opposite direction operations (ODO). The official Pilot/Controller Glossary defines ODO: “Aircraft are operating in opposite directions when: a. They are following the same track in reciprocal directions; or b. Their tracks are parallel and the aircraft are flying in reciprocal directions; or c. Their tracks intersect at an angle of more than 135 degrees.”

Simply put, planes converging more-or-less head on is an ODO. While this can happen in any phase of flight, the context we’re discussing is an aircraft landing or departing a runway contrary to the established flow of traffic.

Occasionally, situations occur that force the FAA to examine its procedures and modify them if needed. The bigger the, uh, “situation,” resulting changes are more likely and more dramatic. That’s precisely what happened with opposite direction ops.

The Good Old Days

Up until Summer 2012, running ODOs was fairly straightforward. It only required good judgment and awareness of the obvious risks. We are, after all, talking about airplanes running at each other from opposite ends of the same runway.

If a pilot requested an ODO departure, I’d examine the big picture. Was the active runway flush with arrivals and its hold short line packed with ready-to-go departures going in the “correct” direction? I may have told him, “Expect indefinite delay,” or just flat out, “Unable. Say intentions.”

However, if an ODO wouldn’t hurt our flow, I’d accommodate it all day.

Our early morning departures were one big ODO. If American wanted Runway 9, Fedex wanted 27, Jet Blue wanted 36, and United wanted 18, it was no problem. I’d tell the departure controller which aircraft was coming off which piece of concrete, clear one guy for takeoff, and the moment he was off the departure end, clear another aircraft in the reciprocal direction. Our tower crew called it “dial-a-runway.”

The same applied to late night arrivals, when all of our RON (Remain Over Night) airliners started flocking to the field. Approach just let us know which runway each wanted, we’d approve it, and Approach sequenced them appropriately, spaced so the preceding aircraft would be off the runway before the opposing one crossed the threshold.

Mixing and Matching

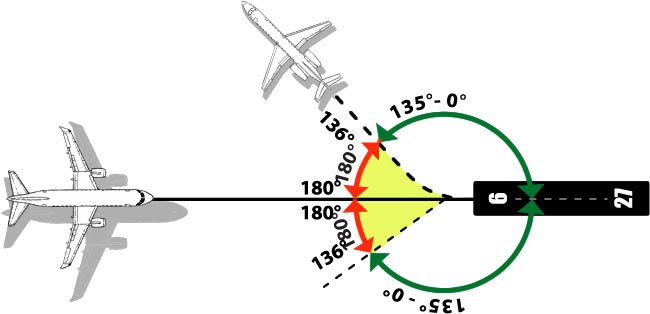

Just departures or just arrivals were fairly easy. Once we mixed opposite direction arrivals and departures, we had to be especially careful with separation requirements. We could, of course, apply visual separation, either from the tower watching both aircraft or if one pilot had the opposing aircraft in sight. Radar separation between IFR airplanes requires 1000 feet vertical separation or three miles laterally for radar approach controls. (Centers need five miles.)

Approach and tower controllers could also use course divergence instead of the 3-or-1000 rule. To apply this to ODO aircraft, both aircraft’s courses must differ by at least 135 degrees. (See the image on the next page.) It takes common sense and awareness of aircraft performance to apply all of these rules. Otherwise, bad things could happen.

Imagine a Boeing 737 at 150 knots on a five-mile final to Runway 27. A Cessna Citation X requests an ODO, to depart Runway 9. If I launch the Citation, by the time he’s lifting, the 737 would be inside three miles out and I’d have over a 300 knot head-on closure rate between two aircraft. I could force the Citation to turn tight to either 045 or 135—creating ODO course divergence—and apply tower-provided visual separation until I had that divergence. The worst case is that the 737 gets a go-around and a turn away from the departure.

In reality, I’d avoid all that crazy risk, let the 737 land, and then clear the Citation to go. We’re trained to keep sufficient space between ODO arrivals and departures, not to create conflicts. Not to say we don’t run things tight on occasion, but those should be highly mitigated risks taking into account aircraft speed, distance, types and maneuverability. For instance, swap the aforementioned jets for a pair of 100-knot Piper Cherokees, and it would’ve worked great, since they’re slower, more nimble aircraft.

Nevertheless, no amount of instruction, talent or experience can overcome human fallibility or the law of averages. Controllers make mistakes every single day. Saying “right” turn instead of “left.” “Traffic, nine o’clock” instead of “three o’clock.” Most are instantly caught and corrected and never get noticed off-frequency. However, when a mistake balloons into a huge mess involving multiple airliners and hundreds of passengers, it’s going to get some attention.

Chain Reaction

July 31, 2012: Reagan National Airport in Washington D.C. lies just south of the prohibited areas surrounding the U.S. Capitol Building and the White House. Visual approaches to its longest runway—Runway 1/19—are tightly controlled and follow the Potomac River. Northbound arrivals to Runway 1 follow the Mount Vernon Visual Runway 1 chart, and southbound landers track the River Visual Runway 19.

Thunderstorms were building south of the airport. The northerly Mount Vernon arrivals were having trouble getting into Runway 1. A supervisor at Potomac Approach called the tower supervisor to ask if they could change to Runway 19.

The tower supervisor was occupied, so another staffer answered. The approach supervisor asked if they could “flush them all into 19.” The tower staffer told Approach, “Go ahead and run them in quickly.” The approach supervisor hung up and coordinated a runway change with his radar controllers.

Unfortunately, the tower staffer misheard Approach’s request. She thought he was asking for tighter spacing between arrivals to Runway 1. She had no idea that Approach was swinging the arrivals around to Runway 19, right in the face of the departures. With her, the first link in the communication chain broke.

From Bad to Worse

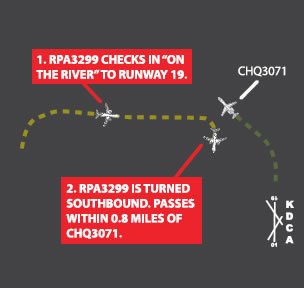

In the middle of this situation was the unsuspecting tower controller. Unaware that anything had changed, she cleared two aircraft for takeoff on runway 1: a Chautauqua Airlines Embraer 135 (CHQ3071), followed by a Republic Airlines Embraer 170 (RPA3467). Both were assigned standard northwesterly routes that would turn them away from prohibited airspace.

As CHQ started its climb, Tower got a nasty shock. A second Republic Embraer 170—RPA3329—checked in “on the river,” eastbound on the River Visual to Runway 19, converging with the climbing, northwest-bound CHQ aircraft. Tower directed RPA3299 to turn southbound, heading 180. The two aircraft missed one another by only 0.8 nautical miles and 800 feet, well below the three miles and 1000 feet required. That was an operational error, “a deal” in ATC shorthand.

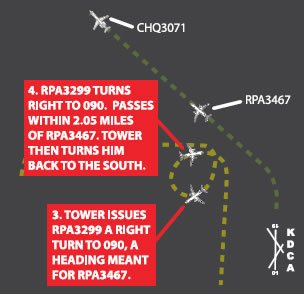

Things escalated. RPA3467 had also departed on a north-northwest heading. He was almost abeam the still southbound RPA3299, and his route would put it well behind the other Embraer 170.

At approach, the supervisor saw what was happening and called Tower again. This time, the actual supervisor picked up. “Hey,” Approach asked him, “what are you guys doing launching north? Yeah, remember?” The surprised tower sup—who didn’t, in fact, remember because he hadn’t been part of the original conversation—dropped the phone and ran to the tower controller.

He instructed Tower to issue a right turn to 090. He intended that for the departing RPA3467, who was still northbound, possibly to bend him further away. Unfortunately, inexplicably, Tower issued them to the now southbound arriving RPA3299. The NTSB report states: “He [the supervisor] did not immediately recognize that the local [Tower] controller had misunderstood his direction because both aircraft were Republic Airlines flights, he heard her instruct a Republic flight to turn, and he was uncertain about the flight numbers of each aircraft.”

The end result was that RPA3299 swung right, a 270-degree turn all the way around to heading 090, and wound up on a converging course with the northwest-bound departing RPA3467. The radar track showed the two Republic airplanes got within 2.05NM and 800 feet of each other—another deal.

One Bad Nail, Many Hammers

Other ODO incidents had occurred here and there, but this one lit off the firestorm. The media got wind of the events and painted a histrionic picture of an already-ugly situation. The talking heads on TV demanded that the FAA “do something.” Secretary of Transportation Ray Lahood promised, “We will get to the bottom of this, and we will take all appropriate action to prevent similar miscommunication in the future.”

A week after the incident, the FAA indeed took action—big time. Pending new procedures, it suspended opposite direction operations at all Part 139 airports (the ones that handle the majority of commercial airline traffic). The only exceptions were emergencies and official FAA flight inspections.

For me and many other controllers around the country, this was incredibly frustrating. A facility across the country had fouled up, but we all had to pay for it. By “we,” I mean both controllers and pilots.

ATC exists to provide services to the flying public. Now those services had been curtailed. Gone was the morning “dial-a-runway.” Gone was a chance for time-critical air-ambulance flights to shave a few minutes off their flights. Gone was the freedom of choice when fast-moving weather barreled in and pilots wanted to take off from whichever runway would keep them out of the storms.

As we always do in ATC, we found workarounds. The main designator for the runway in use is our ATIS broadcast. If I had an air ambulance requesting opposite direction, and nothing else going on, I’d quickly record a new ATIS declaring the formerly “opposite” runway as the active, coordinate this with Approach, and clear the Medevac for takeoff. Once he was airborne, I’d re-record the ATIS with the original runway.

All that took some work, but if someone needed it and I had the time, why not perform the service? We get paid to sort these things out, but even that was just a band-aid fix.

The New Rules Stipulated

The wholesale ban didn’t last, thankfully. Affected ATC facilities could resume ODO as soon as they developed new internal procedures that met three key requirements. First up? Traffic calls. When running two opposing aircraft to the same runway, we’re now required to tell them about each other. It was obviously good practice to do so before, but now it’s required. Surprises aren’t always welcome, especially the “head-on” kind.

Second, arrivals require designated cutoff points. Before the changes, ATC simply used judgment to ensure spacing. Picture the ODO example I used early on (one guy departing 9, another on a five-mile final to 27), and that both aircraft were IFR Piper Cherokees. Gauging their speed and distance, I could launch the 9 departure on a 045 or 135 heading with plenty of room before the 27 arrival became a factor.

The new regs replace that freedom with hard cutoff points. For an arrival-departure scenario, if an arrival is inside a certain distance to the airport, we can’t clear an opposite-direction takeoff. Our airport uses 10 miles for turbine aircraft and seven miles for piston airplanes/helicopters. In the Piper scenario, with the arrival only five miles out, I’d have to hold the departure.

There are different cutoffs for arrival-arrival conflicts. If two arrivals are inbound to opposite ends of the same runway, the second one can’t get closer than seven miles before the first one crosses the threshold. This allows room if the first aircraft goes around.

The final major change involves coordination procedures, which was really the failure point in the Reagan National situation. It wasn’t like Tower was purposely running both Republic flights to opposing ends of the same runway and botched the spacing. It was basic miscommunication. The new rules require extreme clarity: “All coordination must be on a recorded line, state ‘opposite direction,’ and include call sign, type, and arrival or departure runway.”

The specifics of these procedures are developed on a per-airport basis, and each airport is subject to the guidance of the FAA district under which it operates. That means you’ll encounter different procedures at different airports. Some cutoffs points are 15 miles away. Some are five. Some only allow VFR opposite direction. Some still prohibit all ODO—even VFR pattern traffic and the FAA’s own Flight Inspections—except for emergencies.

These new regs clearly attacked the situation “head on” and mandated increased clarity and safety, while sacrificing a good deal of flexibility. I certainly miss how creative we could be with our traffic flow. Will the FAA ever allow us to return to the old “dial-a-runway” days? Who knows? In the meantime, controllers and pilots just have to play by the current rules. If you’re requesting an ODO yourself, you might be waiting longer than you hoped to get what used to be easy.

Tarrance Kramer works his traffic right ways, sideways, and opposite ways, somewhere in the Midwest.