We often think of autumn as the end of summer, but it’s much more than that. Autumn starts on the equinox and ends at the winter solstice, so meteorologically the northern hemisphere is already hurtling headlong into the cool season, with fall ending at the time of minimum insolation. Fall would be a bitterly cold season if not for so much summer heat that was stored in the surrounding ocean waters.

The most immediate change that meteorologists and pilots see in the weather pattern is an increase in the tropospheric flow across the United States and southern Canada at all levels. This starts in earnest in September and continues through October. Temperatures decrease rapidly in the polar regions as fall progresses, dramatically strengthening temperature contrasts between high latitudes and the tropics. This enhances the jet stream pattern and surface patterns alike. So across the board we see an increase in clear air and mechanical turbulence everywhere.

It’s safe to say that IFR readers aren’t content just flying the local pattern on weekends—”accomplished” pilots get maximum utility from their craft. With unfamiliar geography and a change of seasons, it’s a good time to look at what you can expect across the U.S. After all, this column provides less advice than perspective and insight from the mind of a forecaster. From the big picture, you can better anticipate what’s going on when an accurate forecast isn’t available.

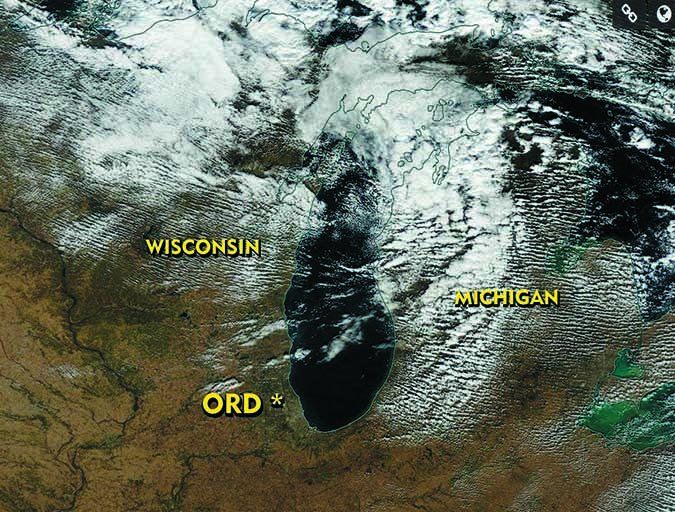

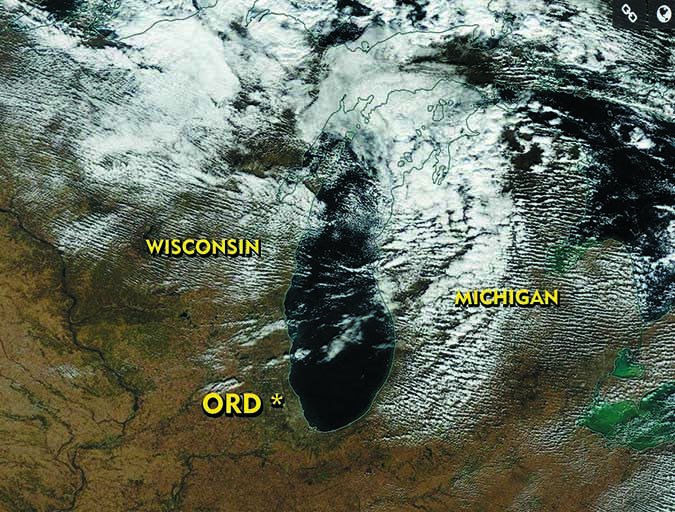

Great Lakes Region

The North American Great Lakes represent the largest group of freshwater lakes on Earth, spanning 94,000 square miles. So it comes as no surprise that they have a tremendous effect on the weather you encounter. In the autumn months, they represent a vast storehouse of heat and moisture, and this is a major weather maker whenever fresh cold air outbreaks roll through the region. With the onset of winter, the temperatures finally cool enough to where fresh cold air outbreaks are not as much of a factor.

When the water is still warm, heat and moisture transfer into the air lying above. This has little effect in summer, but when frigid polar air blows in from the northwest, the cold air mass destabilizes. (Think “cold over hot;” see Chapter 6 of the FAA’s Aviation Weather.) The lowest layers of the atmosphere become very warm, humid, and buoyant, and the result is clouds and precipitation.

In benign situations, “lake effect” clouds develop, consisting of stratus over the waters and shores, and stratocumulus up to 50-100 nm inland. In more unstable situations, the clouds will produce drizzle, light rain, even snow flurries, or snow showers. The favored locations for this bad weather are on the southern, southeastern, and eastern shorelines of each lake, particularly in November and December. In unusual cold air outbreaks with northeast or east winds, the southwest and western shores can be affected, bringing surprise IFR to places like Chicago, Milwaukee, and Duluth.

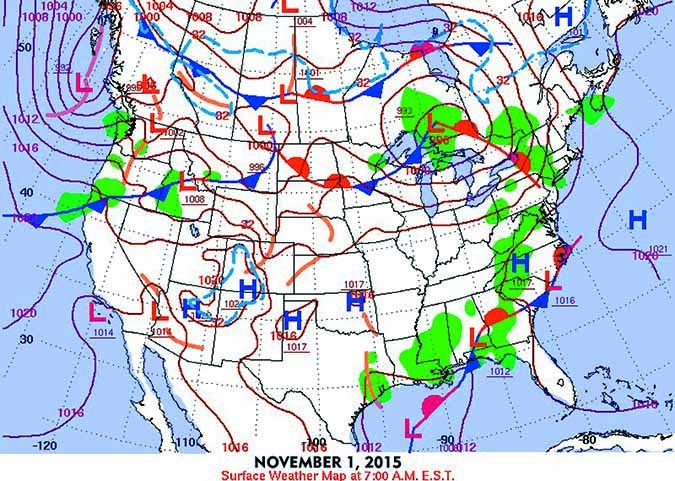

Otherwise, the region is mostly dominated by increasingly frequent passage of cold fronts as late September and October wear on. Flying for the most part will be good with brief windows of bad weather if you’re south of the surface low track, but if you’re ahead of it or to the north, be prepared for the worst and pay close attention to your alternates.

NASA

West Coast

Stratus and fog tends to cover much of the North Pacific Ocean just off the coast of California. This forms within a “marine layer,” which is capped under warm, subsiding air. Pilots operating from airports in San Diego all the way up the coast to Crescent City and northward into Oregon are well acquainted with the marine layer sloshing back and forth day to night during the summer.

As fall progresses, the heat low covering southwest deserts begins weakening. This causes the flow from the cool ocean regions toward Arizona and Nevada to subside. Thus, the marine layer and low clouds makes less headway on shore, and we see more good flying weather across California. September is a perfect month for flying there.

But with the first rains of fall, fog problems soon begin affecting interior regions, including the San Joaquin Valley, and can be compounded over irrigated farmland around Stockton and Fresno. The probability of fog increases as fall wears on, reaching a peak during mid-winter. During the worst of it, days can pass before the weather clears.

At the start of summer, hurricane season is in full effect in the tropical regions, including south of Baja California. Occasionally some of these hurricanes and tropical storms can reach as far north as San Diego and Los Angeles. This is most likely in August, but a risk still persists into September and early October. Some systems can also move inland into the Mojave Desert and Arizona desert regions, producing mostly elevated showers and a bumpy ride.

As cool air builds across the Great Basin, it produces dry easterly winds that blow across the coastal range. When these are strong, they produce the famous Santa Ana winds. The peak for Santa Ana wind events is in late October and November. Low level turbulence and wind shear are the main hazards.

Great Basin & Southwest

The Great Basin of northern Nevada and adjacent parts of other states is one of the first regions of the United States to transition into a true cool-season pattern. This is because of the dry air and lack of proximity to warm ocean waters. Cool nights are the rule. By October 10, nightly lows are normally below freezing in places like Elko and Winnemucca.

This results in the gradual development of a semi-permanent high pressure area. This is felt strongest at places like Las Vegas, where northerly winds become dominant starting in October. These Great Basin winds sometimes strengthen and filter southwestward into California, producing the Santa Ana winds felt there later in the fall.

In Arizona, the monsoon thunderstorm season that peaks in early August rapidly comes to an end, yielding excellent flying weather by October. It’s only in November that winter storms become a concern, initially affecting mostly Utah and northern Arizona and producing only brief periods of showery weather in Phoenix down into Tucson.

Pacific Northwest

As autumn rolls in, Pacific storm systems south of the Aleutian Islands become active and organized frontal systems move onto the British Columbia coast with increasing regularity. Some systems will progress down onto the Washington and Oregon coasts later in the season. The predictable result is a lot of rain and widespread IMC. Stronger systems can produce major wind events. Some folks still remember the October 12, 1962 storm that brought hurricane-force winds to the coastal region. These high winds rarely get very far inland.

Nighttime fog is a major problem, occurring at any location where there’s strong radiational cooling and ground moisture. October is the most favored month for fog problems around Seattle and Portland. When you see high pressure on the surface map covering Seattle or producing light northerly flow, that’s a good sign for fog. This fog normally breaks up by late morning.

NOAA

Great Plains

Early fall brings some of the best flying weather to the central U.S., thanks to stagnant patterns and weak upper-level winds. In fact, in Texas and Oklahoma early fall is sort of an extension of summer. The Gulf of Mexico is still a major source of moisture, though, so severe weather days occasionally visit in October and November, and even in December in Texas.

However the main story affecting the Great Plains is loss of heating in the Canadian polar regions, which strengthens polar high pressure areas. These begin rolling southward across the Great Plains in September, bringing much cooler air and generally MVFR/VFR conditions and bumpy rides. The Dakotas are affected by strong cold-air outbreaks as early as August, while in Texas and Oklahoma they are normally not seen until mid-October. Sometimes the systems will come across Colorado and New Mexico from the Pacific. These are almost always wetter with a high chance of accompanying thunderstorms.

The track of surface lows is important. As a general rule, they tell you a lot about what kind of flying weather will occur. If you’re south of the surface low, you’ll mostly see a brief window of shower or thunderstorm activity, with VFR conditions and gusty winds quickly following. But if you’re north of the surface low, you’re much more likely to have low ceilings and visibility, lasting about 12 to 24 hours.

The Great Plains slope upward and to the west, which means that any easterly component to the surface winds favors upslope flow. This produces adiabatic lift, and favors clouds, fog, and even light precipitation if the air-mass humidity is high enough. This is why polar outbreaks into the Great Lakes region must be watched, as this often puts the Great Plains under an easterly flow and socks in places like Tulsa and Wichita.

Along the Rockies in Wyoming and Colorado, the increasing upper-level flow brings a risk of downslope winds and mountain waves. This is mostly a problem during the winter and spring, but these events do take place with increasing frequency in the fall. Watch for this whenever there is a strong westerly flow at the surface along the Rockies, particularly along and just behind a Pacific cold front.

Southeast

In the southeastern states, the reduction of solar heating brings a gradual respite from the frequent afternoon thunderstorms that accompany the summer months. September and October bring some excellent flying conditions. Atlanta and New Orleans normally see their driest weeks of the year in mid and late October, respectively. However as we get into November, strong frontal systems make their way into the area with increasing regularity. This brings two factors into play.

First, the southeast United States is largely influenced by the rich moisture from the Gulf of Mexico, which is still quite warm from its early September peak water temperature. Although July is the stormiest month for the Southeast with April bringing most of the severe weather and tornadoes, there’s a distinct secondary maxima that occurs in November, caused by the contrast between these warm, moist Gulf waters and cold polar air. Extended areas of organized thunderstorms are common and tend to follow these Pacific and Canadian fronts as they progress eastward. In these storms, you can expect tornadoes and hail.

After fronts have passed and cool, stagnant high pressure is now overlying the East Coast, the rich Gulf moisture riding over stagnant cool air will yield many days of cloudy weather. These ceilings are often low enough in the morning for IMC and lift to marginal VMC and even decent VMC in the afternoon. They cycle repeats as the ceilings lower again at night.

Hurricane season peaks around September 10, so autumn starts out with a distinct risk of tropical storm and hurricane action along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. This gradually tapers down through the months of October and November. If your flight plans will take you southeast, it’s smart to bookmark the National Hurricane Center website at www.nhc.noaa.gov and keep tabs on what’s going on.

Northeast

The northeast United States is mostly affected by the increasing tempo of weather systems coming from the western United States and Canada, and the coastal regions are at the mercy of hurricane season, as storms recurve northward and transition to a “baroclinic” system. Eastern parts of North Carolina, up to Long Island and southeast New England are frequently grazed by these systems as they move northeast into the Atlantic. These systems are easy to avoid with a little early planning.

Fortunately the “superstorms” that commonly affect the Washington, New York, and Boston area are rather uncommon in the fall because they require a strong, southern storm track plus lots of frigid polar air pouring in from Canada over the Gulf Stream waters.

The majority of frontal systems in the fall cross the Great Lakes and move into Quebec or New England, placing the northeast under the southern edge of the storm track. As a result, flying conditions tend to be pretty good, deteriorating only along the frontal zones. With enough moisture, however, these fronts can sometimes produce large lines of storms and showers.

Overall

A lot of good flying weather can be found during the transition from summer to winter weather patterns. Nonetheless, each region of the country still has its weather hazards that deserve caution and advanced planning. Understanding the general patterns can help you anticipate some of the hazards that are present in autumn.

As we discussed, each region offers its own challenges where the flying weather in one situation might be good to excellent, while a slight change can mean low clouds and poor visibility in rain. This gives us good reason to study the individual regional patterns. Of course, throughout the country as temperatures fall, ice becomes an increasing possibility to add into your mix of preflight planning.

Be safe out there, and keep an eye on the weather. It’s a season of much change.

Tim Vasquez is a professional meteorologist living in Palestine, Texas. See his web page at Weathergraphics.com.