The only reason for VORs is for airways and instrument approaches. With GPS navigation taking over, it’s difficult to cost-justify ground-based navigation sources like VORs, many of which are nearing the end of their lives. T and Q routes are popping up, reducing the need for VOR-based airways, and many of us would prefer to fly a GPS-based approach than all the other types. Face it: GPS is in; VORs are out.

A few years ago, the FAA wanted to axe half the VORs, but users have collectively pushed back. The current plan is to trim the 967 existing VORs by 300, in three phases of 100 each by 2025.

But, it’s a chicken-or-the-egg thing. They can’t get rid of the VORs until they get rid of the airways and the approaches. GPS-direct navigation is common already. So, eliminating airways should be reasonably simple. That leaves approaches as the limitation and the short-term solution. So, for now, the FAA’s focus is on eliminating ground-based approaches.

Getting Started

This can be tricky. For example, the FAA was forced to rebuild the BDR VOR in Bedford, Connecticut after Hurricane Sandy destroyed it—even though they originally wanted to remove it from service—because 14 approaches depended on it. No, an orderly plan of redesign and reduction of airways and approaches must precede removal of VORs.

The FAA hired the impartial Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) to help them develop a methodology that would effectively identify ground-based approaches (GBAs) that could be scrapped. The FSF was contracted to “develop a process to identify and ultimately cancel underutilized or redundant instrument approach procedures.”

The FSF delivered its study in early 2011. They analyzed data from questionnaires sent to major stakeholders across the aviation spectrum, including AOPA, three airline organizations, the National Business Aircraft Association and the U.S. Air Force. The FSF then developed criteria that the FAA applied. In April 2015, the hammer fell when the FAA published its list of 736 approaches it wanted to end. To see the list of those approaches initially on the block, search the web for the Excel file “Underutilized or Redundant IAPs the FAA Proposes to Cancel.”

Cancellation Criteria

The plan is to decommission under utilized or redundant ground-based approaches, which are expensive to maintain, and replace them with less-expensive satellite-based approaches.

In determining “underutilized” approaches, the FAA relied on ATC statistics about how often a given approach was flown. These statistics later proved flawed because most ATC facilities only count those flown under IFR and not practice VFR approaches. As a result, many heavily-used practice approaches are on the chopping block even though they remain useful for proficiency.

Legacy approaches considered low hanging fruit include NDBs (Surely, you’re not surprised.), those employing VOR/DME-based area navigation (as provided by the once-popular King KNS-80), and redundant or underused VOR approaches. The FAA and FSF also discussed reducing the over 10,000 approaches with circling-only minimums at locations where operational impact would be small.

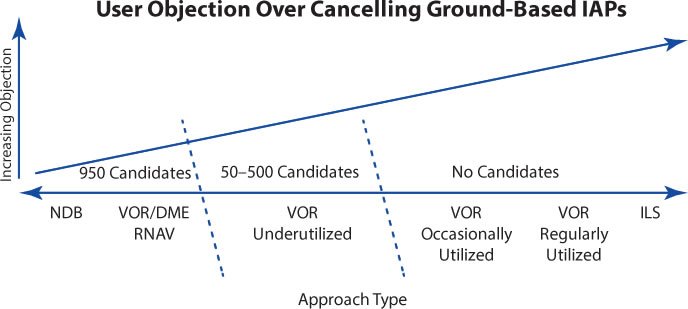

As the graphic shows, there is significant industry pushback when the prospect of reducing VOR approaches on any scale is raised, even to the 736 carefully screened for lack of use and redundancy. The pushback factor rises dramatically when VOR approaches used regularly are considered for deletion.

Another barrier to decommissioning GBAs and VORs is that non-WAAS GPS-navigator-equipped aircraft must have an alternative means of navigation available. That’s a subtle way of saying they need VORs. Speaking of alternates, recall that the requirement for an approach to serve as a filed alternate is that the aircraft must have equipment to fly the approaches, in this case GBAs at the alternates, too. In an effort to keep most of the people happy most of the time, it became obvious that the FAA could only cut so deep.

While NDBs remain in common use throughout most of the world, they’re becoming extinct in the U.S. Consequently, none of the responding organizations expressed any real opposition to eliminating all but a small number of NDB approaches to be used for training.

Phase Them Out

The FSF recommended a two-phase approach toward decommissioning. The first phase targets NDB and VOR/DME RNAV approaches. Only 701 NDB and six VOR/DME RNAV approaches remain. These reductions will barely be felt, given the nearly 17,000 ground-based approaches on the books today. Even here, the FSF attached a caveat that there should be alternative approaches, either GPS or ground-based, with lower minimums to the same runway ends.

Selecting underused VOR approaches to cancel gets a bit trickier. The FSF recommended giving airports with only one VOR or ILS ground-based approach a pass. If an airport has but one approach, the FSF is wisely choosing to leave it in place. Similarly, VOR approaches would remain if the airport needs them for backup as part of the MON.

After this first-pass winnowing, approaches should be considered for cancellation if the VOR that serves them is scheduled for decommissioning within three years. Plus, airports rich in approaches, such as those having two or more VOR approaches with existing GPS approaches, are likely to see their redundant VOR approaches on the kill list. Richer airports with multiple ILS, VOR and GPS approaches are sure to lose some of the less-used approaches.

My own airport falls in this last category. We have three GPS approaches, an ILS and a rarely-used VOR approach. Few would notice and fewer would care if the VOR approach disappeared. Indeed, it is listed as one of the approaches scheduled for decommissioning—the FAA’s methodology seems to be working.

Interviewed airspace users had some thoughtful evaluation criteria to add. Some suggested not eliminating too many approaches per reduction cycle. If a VOR approach serves the same runway end as an ILS, eliminate the VOR (as they’re doing at my airport). Many respondents encouraged eliminating circling minimums if there are GPS approaches to all runway ends, and provided there are multiple GBAs available.

In my area, a nearby airport has two GPS approaches to each runway end plus a VOR/DME approach with circling minimums only. This approach is not on the deletion list because it serves non-GPS-equipped aircraft. This is rather ephemeral reasoning because more and more GA aircraft are likely to have a GPS navigator compared to a DME. In this case, both GPS approaches have lower minimums as an added benefit to using them.

A few respondents offered some broad, well-reasoned criteria to use when choosing which approaches to decommission: Offer fewer approaches at good-weather airports as in the southwest; don’t eliminate the approach with the lowest minimums at an airport and don’t eliminate any approach that increases the need to circle. This last suggestion is particularly compelling because statistically, the circling approach is the most dangerous maneuver in all of IFR.

Let’s Think Positive

Having shown the stick, the FSF then suggested looking at the carrot. The aviation community generally supports the FAA’s efforts to use more GPS approaches and non-precision GBAs less. Note the proviso. The ILS remains the gold standard of approaches with vertical guidance. Vertical guidance is a proven safety component. Between 1984 and 2007, three-quarters of airline accidents occurred when vertical guidance was not available or not used. Statistics show that precision approaches are much safer for GA than NPAs of any type.

In the last five years, the FAA deleted 57 Category I ILS approaches, taking the number of them from 1339 to 1282. During the same period, the number of LPVs has risen sharply from 2329 to 3554, adding 1225 of these precision approaches. These approaches serve 1732 airports, and quite encouragingly, 989 of these airports have no ILS. Without the economies of an LPV over an ILS, precision approaches with low minimums would be denied to the nearly 1000 communities those airports serve. FAA policy is not to install any more ILSes; using LPVs instead. The numbers show they’re doing just that. There are also nearly 1149 more LNAV/VNAV approaches, now totaling 3429.

GPS approaches are favored for their quality and their increasing numbers. AOPA reports that over 70 percent of its members employ GPS. One of the key FSF recommendations was that the FAA focus on “RNAV [GPS] everywhere.” They encouraged the FAA to publish a policy stating that ATC operations in the U.S. are primarily GPS-based and are the normal method of operating.

As a practical matter, this is already happening; ATC seems to assume that every aircraft has GPS. ATC is required to offer approaches with the lowest minimums, and as we covered previously (see “Nextgen Update” in July 2015), that’s more likely than ever since GPS approaches with vertical guidance outnumber ILSes by over five to one. This constitutes a significant paradigm shift for many of us. To this end, the FSF recommended that a GPS procedure be published at every airport, essentially competing with existing ground-based procedures. The minimums would have to be competitive, and if lower, might “make the sale.”

In this spirit, FSF also suggested that GPS overlay procedures, those that say “VOR or GPS” in the title should be eliminated in favor of a GPS-only approach with at least the same and preferably lower minimums.

Airways

The FSF advocated eliminating Victor and Jet airways of which 663 and 274 exist respectively. Although filing direct to destination seldom works, the route you get will largely be direct between fixes. The FAA has normalized non-airway routing; for most of us flying via airways has become the exception. The objective is to get us to think of airways as being used only when needed for other reasons. Of course, for this to truly work, GPS routings can’t be any longer than their airway equivalents and should usually be shorter.

Few GA pilots know much about T-Routes, GPS-based equivalents to Victor airways (below 18,000 feet), even though most navigators that understand airways understand these GPS airways. One big reason is that the mere 101 of them don’t give us enough exposure, making them less likely to be useful.

In the flight levels, Q-routes (GPS-based high-altitude airways) suffer the same malady: only 133 exist compared to 274 Jet routes. The plan is to greatly expand T- and Q-Routes in the congested areas of the northeast and in the LAX-SFO corridor.

One of the more perceptive yet controversial recommendations by the FSF involves the ADS-B mandate. Many of you know that a WAAS receiver is essentially required in order to satisfy stringent ADS-B positional-accuracy specifications. Some installations use a WAAS receiver buried in dedicated ADS-B Out hardware to meet this requirement.

However, the FAA doesn’t require that the same receiver be used for navigation. This can put us in the awkward situation of not being able to fly as accurately as we are tracked. The FSF recommended that the FAA require that such WAAS receivers, also be used for navigation. This would require hooking up the receiver to a display of some type that could get expensive. The benefit is that you get double-duty from the ADS-B Out gear you purchased.

Instrument students should know that the current Practical Test standards will be replaced by scenario-based Airman Certification Standards. (See “Good-Bye PTS; Hello ACS” in the February 2015 issue.) Similarly, the instrument knowledge tests need to de-emphasize VOR airway navigation because it is headed toward obsolescence.

Running the Numbers

In September, 2010 there were about 10,000 GPS approaches; today there are about 4000 more. By contrast, the number of ground-based approaches has decreased slightly by about 340 to about 6,500. Clearly, GBAs are giving way to RNAV approaches, although not on the original schedule the FAA anticipated. (See the figure on this page.)

The original notion was that the number of GBAs would approximately equal the number of GPS approaches at about this time. This is somewhat pessimistic. At this writing the FAA maintains 14,371 GPS approaches and about half that many GBAs.

However slightly, the trend is downward for GBAs. Eliminating 736 ground-based approaches is a modest but real 11 percent decrease. This number will surely decrease in the short term as users push back to retain useful—by their measure—approaches. The safe bet, though, is on the longer term decommissioning of most non-precision GBAs and even some ILSes.

Fred Simonds is an active CFII in Florida. He’s happy to fly any approach even if it means circling. See his web page at www.fredonflying.com