We’re preparing for our flight from Santa Fe, N.M. and there’s been news of an unusually cold late spring storm moving through Colorado. On May 11, of all things, winter storm warnings are already up for Wyoming and much of Colorado. Our bumbling friend Dave called ahead and unfortunately most of the resorts like Aspen and Telluride had already closed for the season (“What a waste,” he complained.) but we found that Arapahoe Basin is still open. So our quest is to get to Denver.

Matt will be at the controls today. As usual, being the resident meteorologist of the group, it’s up to me to keep us out of any nasty weather—a task I complain about to my friends, but secretly enjoy as it stretches my knowledge into practical application. This should prove to be an interesting trip.

Fresh Powder Skiing in May?

Unfortunately we got a late start since we didn’t want to leave Santa Fe without picking up some souvenirs and getting one last meal of huevos rancheros with both red and green chili.

It’s 9:30 a.m. and we’re all set. Pulling up the TAFs, it’s pretty obvious that flying into Denver is not going to happen today. Denver’s Rocky Mountain Metropolitan Airport (Jefferson County) is calling for 400 overcast, one mile in snow, north winds, with a temporary group of half mile in freezing fog. It’s May and Denver is digging out of a snowstorm?

“Yeah, I’m not going to be putting my IFR skills to that big a test just for a chance at some spring skiing,” Matt says. “Why are we even flying to Colorado for a snowstorm? What’s the point?”

“Skiing Colorado in mid-May,” Dave says. “There’s fresh powder on a 70-inch base. We fly there and hole up in a motel for the night. They’ll have the roads plowed by morning, and the sun will burn off what’s left. It will be a piece of cake. Great skiing and we can head into Denver for some wings and beer. That reminds me, we’ve got to pick up sunscreen. The UV will be brutal out on the slopes this time of year.”

Dave’s always a wellspring of crackpot ideas, but with him there’s no shortage of adventure. I’m reminded of an old saying often misattributed to Mark Twain: “Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails.” I wonder who said that. Abraham Lincoln? Churchill? Bill Gates? Well, I read it on the Internet, so probably all of them. This excursion sounds like fun.

I took another look at the weather. “Well, we’re getting in at 1900Z. The problem is that all of northern Colorado is a mess of high wind and IMC with some snow. If we stay 100 miles south of Denver in Pueblo, they’ve got good VFR. Even there, the wind is blowing 30 knots but it’s right down a runway.”

Matt ponders the information. “I’m not enthused about 30 knots, but seeing as there’s no crosswind and it’s VMC, we’ll go ahead and take it.”

“Pueblo’s a longer drive, but I guess I can live with it,” Dave says.

“Easy to say when you’re not driving. Well, I’ll get our weather briefing. Let’s get going.”

Takeoff: In the Sun

They head out to the plane, load up our bags, and Matt starts the walkaround. Given the weather pattern that’s in play today and the conditions we expect to encounter, I decide it’s a good idea to hang back in the FBO for a bit to dig a bit deeper into what’s ahead of us.

Matt knows he’s facing deteriorating conditions, but I don’t think he quite understands what’s up. “Where’s our weatherman?” He asks.

Ever helpful, Dave quickly responds. “He’s inside. Something about having a closer look at the weather before we launch.”

“Oh,” Matt says flatly, now beginning to look a bit concerned.

It’s a gorgeous morning with a few bands of clouds, light winds, and 61 degrees. We pile into the Mooney and start the checklists. As we taxi to the runway, Dave, sensing Matt’s concern, comments about the nice weather. We taxi into position, open the throttles, and head into the New Mexico sky, climbing slowly to our cruise altitude of 11,000 feet. It’s a nice ride and looks good ahead, for now. Matt visibly relaxes a bit.

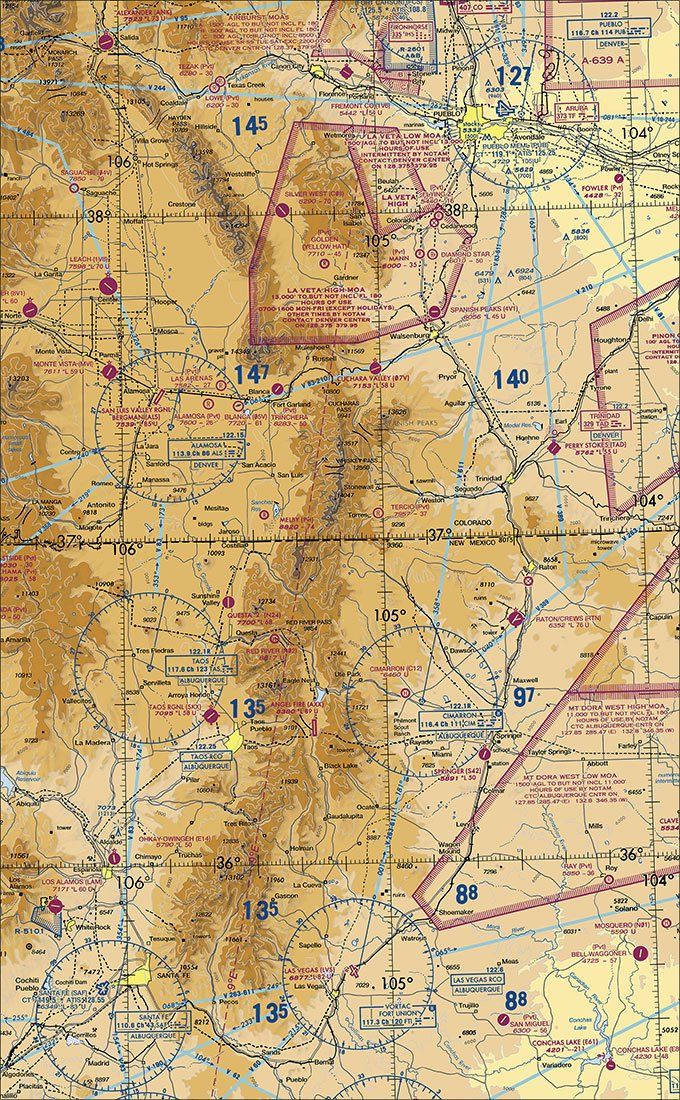

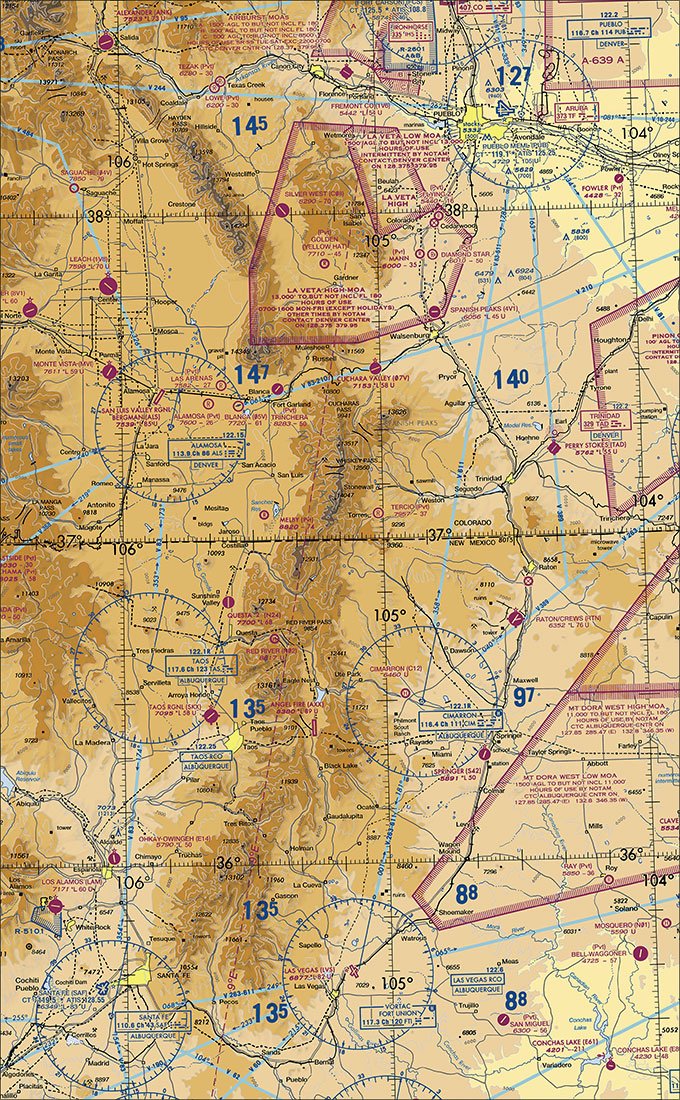

Instead of heading north where there’s weather and MEAs over 14,000 feet, we first head southeast to pick up V60, which will take us to the Fort Union VORTAC, near Las Vegas, N.M. This will keep us over flat terrain the whole way in case we have a problem with the engine. We’ll continue on V611 to the Cimarron VOR, near Raton, then Pueblo.

Although there’s clear blue sky with a few bands of altocumulus, the sky to the north looks like a sea of towering cumulus. In spite of this, the ride is mostly just light to moderate chop. As Matt levels at cruise altitude, I look down and see endless, flat rangeland extending toward the southern horizon.

Cruise: Looking Worse

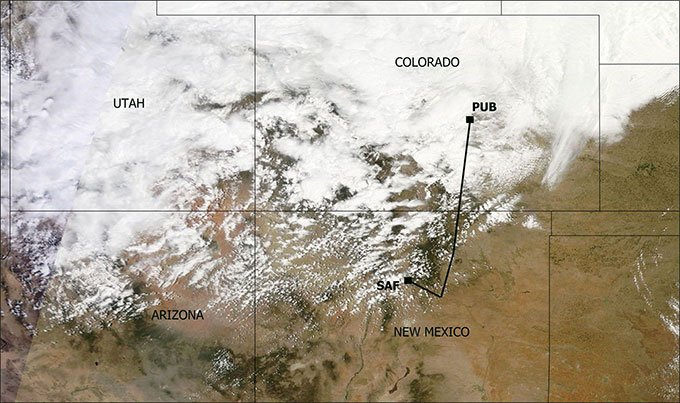

After a short while, we turn northward, gradually pointing the nose toward Pueblo with the mountains on our left. We’re starting to see vigorous towering cumulus clouds rising off all the mountain ranges and forming prolific streamers of glaciated cloud, just like what was shown on the satellite image. There’s also a 40-knot crosswind from the left.

About 45 minutes later as we cross the border into Colorado, we’re in the soup, with the view ahead a featureless gray framed by hypnotic trails of snow. Looking down, though, the ground is clearly visible and I can see a few ranches and hills. We’re not in a cloud, just a snow shower.

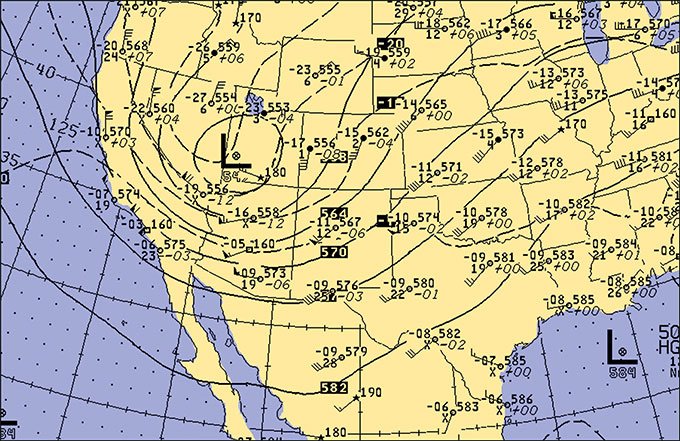

So what’s causing all this weather? First, the wind chart shows a cold-core upper-level low moving across Colorado. These are rather common and tend to trail several hundred miles behind well-developed surface frontal systems.

The frontal system and surface low today is centered in western Kansas, where it’s producing some severe weather. Cold-core lows, as the name suggests, are associated with very cold air aloft: in this case, -10 degrees C at 10,000 feet over the Great Basin region. This, in contrast with the mild temperatures at the surface, produces a very unstable temperature profile, even way out west.

One other characteristic of cold-core lows is the winds throughout the middle and upper troposphere tend to “wrap” around it instead of flow uniformly from west to east as seen in the winds chart. As a result, the mean winds along our route of flight are from southwest to northeast instead of west to east, and the flow tends to be parallel to the mountain ranges rather than perpendicular. This helps limit the extent and intensity of turbulence.

The towering cumulus is abundant, and there would be strong thunderstorms here if not for the fact that moisture is sparse in this Pacific air spreading into Colorado.

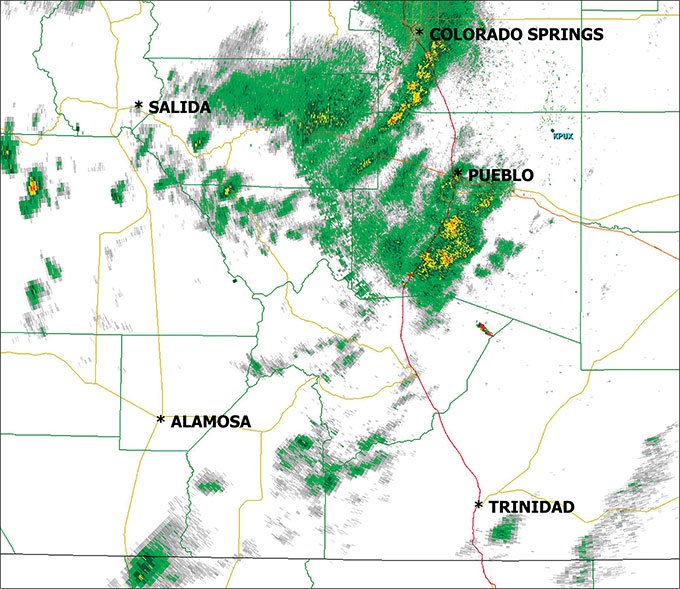

Instead we have shallow, elevated showers that can be seen on the radar image. The bases are several thousand feet above the ground, and the tops are rarely higher than 20-25,000 feet.

Though the showers are capable of producing localized areas of clear icing through a shallow layer, these are easily avoided and the heavier cells are normally small enough to be dodged. Rime ice is more common from these showers. The main hazard is low-level wind shear, since entrainment of dry air into the downdrafts helps accelerate them toward the ground.

One of the other elements thrown into the mix today is a Canadian polar front surging southward through eastern Colorado. This front is driven by a strong high pressure area in Canada.

Although windy conditions at Pueblo, Denver, and Colorado Springs are often suggestive of chinook windstorms, the northerly wind direction paints an entirely different picture. Winds are strong due to the sheer density of the cold air to the north, reinforced by cold pools generated by the elevated showers as they move over the cold air mass. This helps the cold front and the cold air mass surge southward even more quickly.

The Canadian polar air in this type of situation is normally rather shallow, rarely deeper than a few thousand feet. However it can be a prolific source of low-level wind shear and mechanical turbulence within the lowest thousand feet of the atmosphere.

While there are rarely problems late on an approach, aircraft departing in these types of shallow air masses may abruptly lose 20-30 knots of airspeed a minute or two after takeoff, within the transition zone where the strong northerly headwind changes into a strong tailwind. So flattening the climb rate a bit and picking up a little extra airspeed can help provide a little insurance.

Landing: No Sun For Us

Approaching Pueblo we’re in the muck. There have been lots of breaks between the showers with intervals of good visibility, but the snow is relentless and we’re getting moderate chop. We dial in the ASOS for Pueblo. There’s good visibility but winds are gusting to 30 knots right down a runway.

Matt brings us in for the approach on Runway 35. We make a surprisingly smooth touchdown, though a momentary gust keeps us floating for a few tense seconds. We roll out, and taxi over to the FBO where we carefully tie down the airplane.

And, it’s a good thing we were careful with the tiedowns. As we settle in our hotel, hearing the trees thrashing outside and with a gloomy overcast settling in, I pull up the METARs on my smartphone and see Pueblo has 360 degrees at 31 gusting to 43 knots. This is well above what the TAF had anticipated.

Even in 2014, with mesoscale forecast models having seemingly reached a state of perfection, and with top meteorologists working in the National Weather Service offices, the forecasts still often have surprises. The winds were 13 knots stronger than forecast and the front got here two hours early.

Looking all across the region, winds have increased to 30 or 35 knots at most stations. If we had waited another two hours, Pueblo would have been beyond Matt’s capability in the Mooney and we would have been sweating it to our alternate in La Junta, with 30 knot winds not right down the runway. Days like this are a wake-up call to pad in an extra margin of safety.

Dave knocks on the door. “Hey, I just found this flyer. Heard of the Weisbrod Aircraft Museum?” He hands me the flyer and I take a look. A B-29, an A-5 Vigilante, a B-47, an F4D Skyray… Yeah, we’ll have to check this one out. I grab the rental car keys and we go and get Matt. On a day like this I’m hoping most of the good stuff is indoors and there’s coffee or hot chocolate somewhere. Then I realize it’s 45 degrees outside. Maybe I’m not cut out for the slopes.

Tim Vasquez is a professional meteorologist in Norman, Oklahoma. See his website at www.weathergraphics.com.