GPS touches many more systems than most pilots realize. How would a GPS-swaddled pilot do if that one bit of information was denied to every system on the aircraft?

It’s all Chet’s fault. The whole thing had started over beers, with Brian regaling us with details of his latest foray down south in his Cirrus.

“The airliners were diverting around embedded cells and holds were getting issued all the way up Florida coast. But I was heading into Exec and offered a heading to ATC to get me through a gap. Man, you could see the airliners on the traffic page stacked up, but I just slipped down the ILS and was elbow deep in stone crab by 6:30.”

Chet sits on the left of a kerosene-burner by day, but prefers his off days when his Champ lifts off from the pasture behind the barn. Brian’s dig at airlines and his techno-geek-fest would rub Chet the wrong way in both directions.

“That airplane is a house of cards,” Chet grumbles, taking another sip. “You’d be a lost lamb without GPS.”

“Would not.” Brian’s comeback skills are stuck at about fifth grade. “The plane has two GPSs, anyway. Plus two VORs for backup. And I’ve got the iPad.”

“Really?” Chet is smirking now. It’s like watching a cat inching up on a mouse from behind. “Want to put that to the test?” Brian ponders. Chet smiles. The cat’s paw drops firmly on the mouse’s tail.

Black Box Hijinks

A week later, sitting cozy in the right seat of Brian’s Cirrus, Chet is still wearing that smile. Chet laid out for us: Depart Biddeford, Maine, for Mount Washington Regional in New Hampshire. About 70 miles direct on this clear-and-a-million day. But we are to launch VFR and pretend it’s IFR in hard IMC with Chet playing ATC.

I don’t trust smiling airline captains. “What, exactly, are you planning, Chet?”

“It’s safe. I’ve tested it extensively and adjusted the range so it only affects a 30-foot bubble around this airplane.”

Brian looks uneasy. “Is it legal?”

“The less you know, the less you have to lie about on the stand.”

“Isn’t there another way?”

Chet sighs. “I could yank that pretty headliner and pull both GPS antennas. And take that infernal iPad away.”

Brian looks up at his headliner, and then launches for a west departure.

We’re leveling off at 6500 when the messages cascade over the MFD and twin Garmin GPSs: “No GPS Position, Dead Reckoning—Use other navigation, TAWS failure, Traffic failure, Stormscope failure,” and my personal favorite,

“Searching the Sky.” The iPad is a bit more reserved, simply showing “No fix,” and making the little airplane symbol vanish from the map. Whatever Chet had up his sleeve, it killed every GPS receiver on the airplane.

Brian plays the card he would in the real world with a call to Chet’s mock ATC:

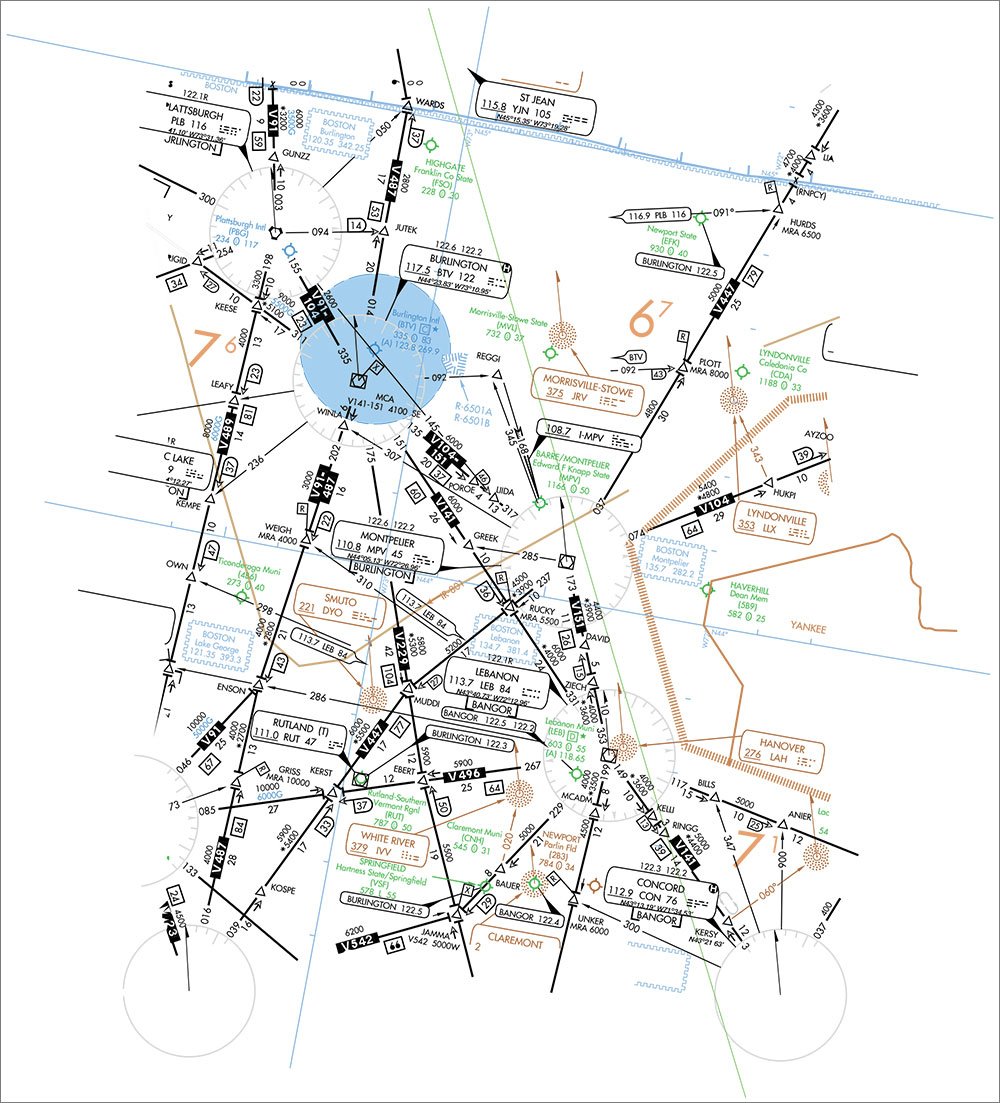

“Portland Approach, Cirrus Five Four Three Charlie Delta. We lost all GPS navigation. We’re declaring an emergency and want vectors for Portland.” But Chet has this covered, calling back as ATC that everybody is having issues, there is a national-security event brewing and we are to join V322 and continue for Mt. Washington until further notice.

Fine, we signed on for this. Brian asks if it’s OK to keep using the autopilot. Chet seems vaguely disgusted: “If you must.” And so it begins.

Rusty? Not the Half Of It

Airway. Right. Brian goes to tune the VOR frequency, but not from the nearest VOR page of the GPS because it doesn’t know where we are anymore. He tries the iPad, but he was on a different screen and now the little Location button won’t center the map. Where’s V322? Where are we?

Brian tosses the iPad back over the seat at me and tells me to hunt somewhere near our route. Chet nods, but hands me a second pair of foggles as I unstrap and slide forward to better see what’s going on up front. I find V322, ask Chet to be my hands, and enter 114.4 for the Manchester VOR.

Meanwhile, I remind Brian how to manually dial a course of 037 on the PFD. “I never use this knob,” he complains. By the time he gets it, we’ve overshot the airway. We flop like a fish on the dock overcorrecting for the winds aloft, which are also absent from the PFD.

“Uh, there’s a bend in the airway,” I say. No GPS means no DME. We need the crossing radial for a turn at WYLIE.

Chet snickers. “Yup, and this Cirrus has only one CDI. But it can be done.” Chet may be a bit of an aviation Luddite at heart, but he used to be a Cirrus-certified instructor and knows the avionics well. The bastard.

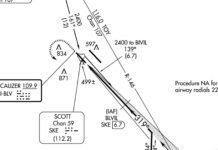

Brian figures it out, pulling up a bearing pointer RMI-style for the Berlin VOR. Just read the tail of the needle to see that we’re on the 170 radial. Ah, crap. It took us so long we’ve missed the turn. Brian gets us back on the airway and starts to brief for Mt. Washington. It has three approaches: Two RNAV, which are right out, and one LOC/NDB. The Cirrus uses GPS in lieu of ADF. We can’t fly a single approach at Mt. Washington.

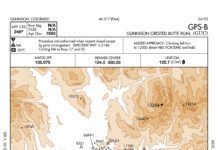

Chet’s having a ball, and now steps in as faux ATC with a descent and holding instructions at Berlin. We try the “vector us outta here” ploy again, but he’s sticking to the story that it’s a national emergency and all pilots are requested to land as soon as possible. OK, fine. Of the three approaches at Berlin, N.H., we can fly one: The VOR-B.

“How far are we from Berlin?” Brian asks. Damned if I know and Chet has us too low to get any other VORs in these hills. Even in my pre-GPS days, I still had DME. I had no idea how much I’d miss it. We still have a map on the MFD, but it’s no longer moving and there’s no reassuring airplane symbol anywhere to be seen.

The needle is getting twitchy, so we’re close. Chet throws us a bone and clears us over the VOR at 4400 feet and for the approach. Brian crosses and turns outbound. About 30 seconds later (we think), he remembers to start a timer. At least some belt-and-suspenders Garmin engineer included a timer function on the Cirrus’ transponder. What are the winds? Ah ha! We still have datalink weather, but to no avail. It’s tied to the GPS flight plan via the trip page, which says, “GPS not reporting active leg,” and nothing else. There are pretty METAR flags saying the system knows what the winds are, but this MFD has no way to pan over and check. I point this out to Brian. Chet is giggling so much I think he’s going to wet himself.

Brian catches the timer not long after crossing the VOR inbound and notices that there’s a course change. We dive and drive, struggling back to the correct final-approach radial and taking a wild guess at a groundspeed for the timing. We’re blind in a valley at the mercy of TERPs and Chet.

“Can I lift these foggles now?”

“Nope.” Chet’s not done with us. “Go missed. Assume you can’t get a word in edgewise on the frequency and that Portland is closed for reasons of national security. While you’re in the hold, figure out if there’s any other approach around here you can fly.”

We hold, only screwing up once when I tell Brian the holding radial is 300 when it’s really 030. Then we start looking for airports. Freyburg? No. Lewiston? No. Augusta, Maine, has nine approaches and we can fly exactly one without GPS; two if we can get alternate missed-approach instructions for the ILS, as it requires an ADF. We do all this while Brian dutifully mumbles his Five Ts with each turn of the hold. “The difference with VOR flying is you actually have to think,” he says.

Chet suggests Laconia, N.H. We accept, and he clears us back down V322.

It Gets Better

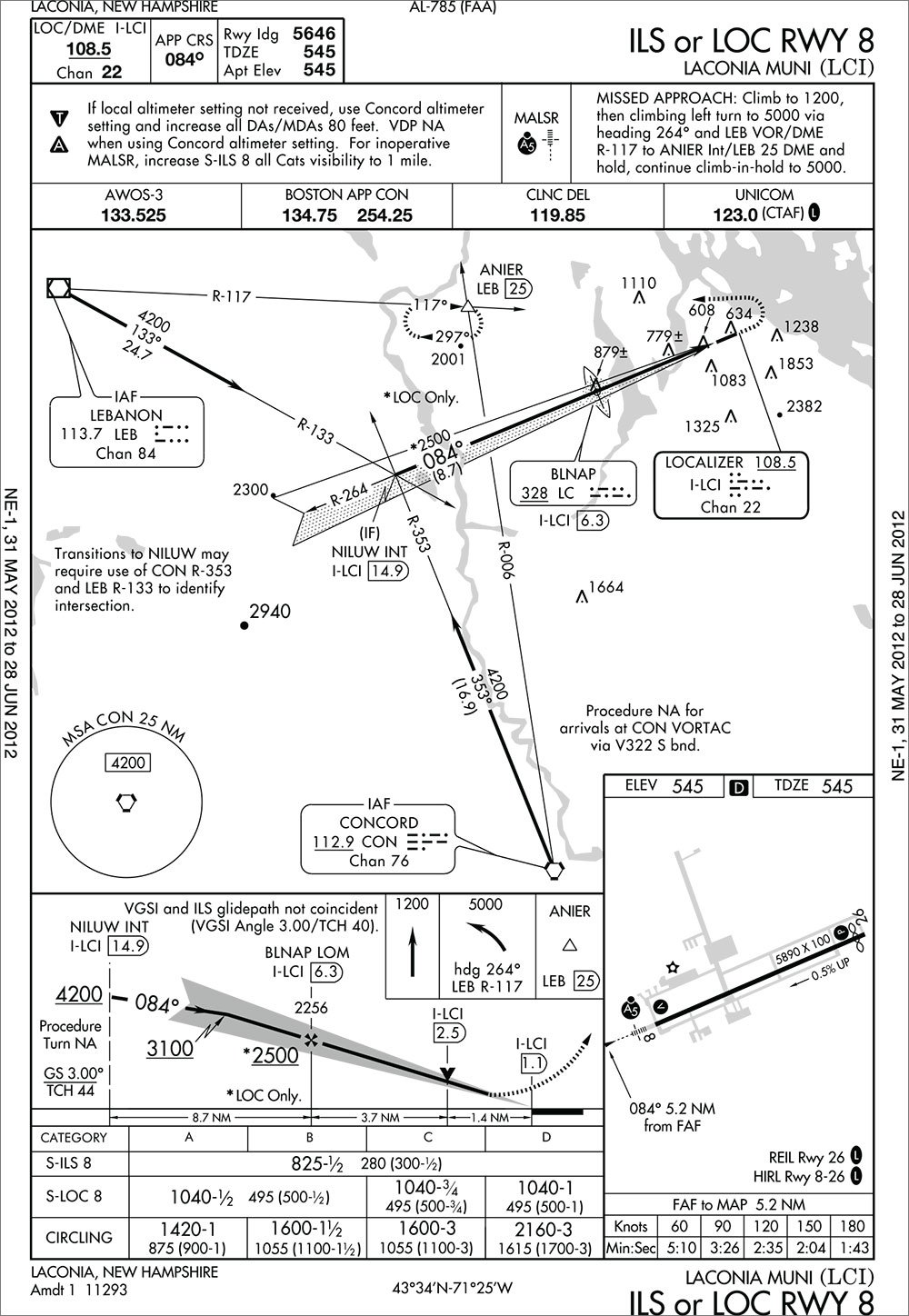

This time, the airway work isn’t so bad, and we have an RMI giving bearings to the Kenebunk VOR, so we pretty much know our position. Chet clears us over the Concord VOR and back for the ILS Runway 8 at Laconia. Brian briefs the chart and points out that the approach is NA for arrivals southbound over Concord. I can hear the grin in his voice.

Chet grumbles and mutters something about ATC allowing it under the circumstances while he stares out the window, presumably scanning for traffic. Ha! Score one for our team. A moment later Chet reminds Brian to switch tanks. The warning message for a tank switch Brian was used to got buried in all the system-failure messages he’d been ignoring for over an hour. Score one more for Chet.

Brian rallies, nails the turn over the VOR and swings around for the approach, flying the RMI needle cocked 15-degrees off our heading, which yields a perfect track up R-353. But the picture on the HSI doesn’t make sense. I point it out and Brian says he doesn’t care, he’s got secondary displays for left-right on the PFD, he can use those.

“Yeah, but why does it say LOC BC?”

Brian realizes that when he didn’t bother loading an approach, even an ILS, from the Garmin navigator, the course needle didn’t auto slew to 084. It’s still on 257 from our trip down V322. The HSI is facing the wrong way and our smart system thinks we’re flying a back course, reversing the sensing for us automatically.

“That might have been confusing,” Chet chuckles. But he’s happy again. Our CRM must be getting the better of his airline half.

Brian nails the ILS, even with the nearly right-angle intercept, and Chet tells him to look up at mins. Brian pours on the coals for the missed. Chet says he’s happy to stop now, but Brian’s on a roll. It’s an oddball missed with a climb and then a climbing turn to an intersection. He catches the Concord radial first and meets the Lebanon VOR radial moments later. He pulles off his foggles and tosses them in Chet’s lap. “First round’s on you, Captain,” he gloats.

Chet raises his hands in acquiescence.

Lessons Learned

Back at the brewpub, all Chet will say as to how he did it was, “It’s amazing what you can buy online from China.”

The biggest surprises were how much we missed DME and times to the next fixes. Next up was not having a top-down view on the map and no weather information. The lack of winds and groundspeed on the approach generated more discomfort than I would have guessed. Had I thought about it, so would the lack of terrain warning and traffic. But I’m pretty sure Chet was looking for the hills and other aircraft between laughing fits.

But most surprising of all was the twin realization that we have 10 out of a dozen eggs in a GPS basket that is clearly easy to disrupt—and that those two remaining eggs were still enough to safely nail a full-procedure ILS.

But then again, Brian and I started in the lonely hell of two VHF radios and black lines on white paper to traverse the milky skies. I wonder aloud whether a pilot raised on glass would fair as well as Brian. How about down the

NextGen line when even more is based on GPS?

Chet shakes his head and orders another round for us all.

What gets lost with GPS

Every advanced cockpit is different, so the exact fallout of complete GPS loss will vary. It’s still impressive how many things besides “direct-to” might get knocked out when there’s no GPS position. You might be surprised how dependent you’ve become on some of them:

Proxy ADF

Proxy DME

Time to fixes

Track- and flight-path markers

Groundspeed

Winds aloft

Traffic alerting

TAWS

Moving maps

Synthetic vision

Stormscope

Autopilot tracking and intercepts

Nearest airports, VORs, etc.

Vertical navigation

HSI autoslew

Automatic frequency switching

Turn anticipation and hold entries

Access to datalink weather

Automatic waypoint data

Automatic approach charts

In addition, many AHRS (digital gyro) systems use GPS position as part of their attitude solution. We know of no certified system that would fail without GPS, but attitude accuracy and response speed could be impaired on some. Some uncertified systems might fail altogether. —Jeff Van West

No actual GPSs were harmed in the making of this article, and Ollie won’t tell the FCC that Chet lives just outside of Burlington, Vt.