Excitement is in the air as you plan the last big requirement for your instrument rating—the “long cross-country.” After that, the only task left will be your three-hour prep. Oh, and the check ride.

Choose the Trip

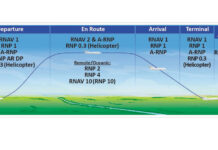

Regarding the long X-C, §61.65(d) says, among other things, that you need to accomplish a flight of 250 NM with three different kinds of instrument approaches. You discuss various options with your instructor starting at your home airport, Aurora State (KUAO) in Oregon. Having done most of your instrument training in the Willamette Valley south of Aurora, your instructor suggests, “Hey, how ‘bout we head north for a change.”

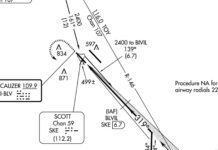

Olympia Regional (KOLM) in Washington State, looks like a good place to stop, rest, and refuel with its two excellent FBOs. How about flying past Olympia and doing an RNAV (GPS) approach at Sanderson Field (KSHN), Shelton, Washington first? Fly the Sanderson approach to the east (Runway 5), the full missed approach procedure, once around the hold at CARRO so you have time to brief for the next approach, then backtrack southbound to Olympia via the VOR-A approach. After that, it’s a straight shot back to Aurora where the LOC-17 will finish the approach requirement.

You notice a problem. “Maestro, it looks like the route KUAO KSHN KOLM KUAO is only 243 NM round trip, according to ForeFlight—not quite enough for the 250 NM requirement.”

“No problem. Add the IAF on the inbound course for Sanderson Field (ULESS), then add the missed approach holding fix (CARRO), and recalculate.”

“Cool,” you reply. “The full route (KUAO ULESS KSHN CARRO KOLM KUAO) now clocks in at 267 NM.”

Fly the Trip

The late morning METAR for Aurora includes BKN020 BKN026 OVC034. Climbing off Runway 35 on the NEWBERG TWO (RNAV) departure, you don the hood after reaching 700 MSL and completing the turn toward UBG (Newberg VORTAC). Pretty soon, you are in and out of clouds on your way up to your assigned altitude of 8000 feet. In fact, by the time you climb through 4000 your instructor says, “You might as well take off the hood and enjoy some ‘actual.’ It’s solid white up here!”

Fast forward to the RNAV (GPS) RWY 5 approach at Sanderson Field where you hide under the hood again thanks to the VFR weather (10SM FEW047 OVC060 15/09). You breeze through the approach from ULESS. At the missed approach point (RW05), you shoot the missed back up into the clouds eastbound to the hold at CARRO.

You request the VOR-A into Olympia and are cleared direct HABOR which is both the IAF and FAF for this approach. Olympia is reporting 10SM FEW034 OVC060 16/08, so you should be just fine with the 880 MSL (672 above airport elevation) circling MDA. Approximately five miles from HABOR, you are instructed to maintain 3000 until HABOR, and cleared for the VOR-A approach into Olympia.

Need a PT?

Sounds simple enough, doesn’t it? HABOR, and cleared. But wait. There’s a HILPT (hold-in-lieu of a procedure turn) at HABOR. Should you proceed straight in on the approach or do you need to fly a turn in the HILPT first?

Good question. How good is your memory on this topic? If you’re not sure, do you have time to look it up? Clearly not, so you query the controller.

He replies: “I have issued the approach clearance that I am able to issue based on your intercept angle.”

Ummm … not helpful. No time to argue or ask for clarification because by now, you are just a few seconds from crossing HABOR.

Your instructor is as dumbfounded as you, but you are quick enough to reply something like, “In that case, we will continue straight in unless you advise otherwise.”

Brilliant answer! Our transmission will be on tape and at least shares any possible blame with the controller. However, you are still nervous as to whether you are doing the proper thing by skipping the HILPT. Fortunately, you are handed off to Olympia tower and land without incident. No Brasher warning (“I’ve got a phone number for you to call…”), no contact from FAA afterwards.

Replay and Research

Now that the incident is in the rear-view mirror, you have time to replay the situation in your mind and accomplish two things: File a NASA ASRS (Aviation Safety Reporting System) report “just in case,” and do some research.

In the AIM, you find section 5-4-6 Approach Clearance, paragraph e, sentence 4: “If proceeding to an IAF with a published course reversal (procedure turn or hold-in-lieu of PT pattern), except when cleared for a straight in approach by ATC, the pilot must [emphasis added] execute the procedure turn/hold-in-lieu of PT, and complete the approach.”

So yes, the AIM says you were required to fly the hold since you were cleared for the approach, but not straight in.

However, from §91.175(j) Limitation on procedure turns: “In the case of a radar vector to a final approach course or fix, a timed approach from a holding fix, or an approach for which the procedure specifies ‘No PT,’ no pilot may make a procedure turn [emphasis added] unless cleared to do so by ATC.” (Nevermind that this directly conflicts with the AIM reference above.)

Were you on a radar vector to the fix? If so, you may not fly the procedure turn. If you were not on a radar vector, then you were required to do the procedure turn.

This hinges on the question as to whether “direct HABOR” is a radar vector. You go back to the AIM for guidance (Pilot/Controller Glossary):

RADAR VECTORING [ICAO]—Provision of navigational guidance to aircraft in the form of specific headings, based on the use of radar.

“Specific headings,” it says. You were not given a specific heading. You were given a specific course (direct HABOR). You get to choose the heading that takes you directly from your then-present position to HABOR.

So, it appears you were not specifically on a radar vector, so you were required to spend time and fuel running around the HILPT racetrack. Good thing you stated your intentions clearly. And good thing you had an instructor with you to take the heat in case you were wrong (tough job, but someone’s gotta do it).

Other Options

Let’s conceive of some other tactics you might have used after the controller failed to answer your question about whether to the fly the HILPT at HABOR:

1. Use the “E” word. You would need to state the nature of the emergency, such as getting low on fuel and concerned that you might end up below minimums if you have to fly the racetrack. (“Two souls on board, 55 minutes of fuel.”) Or, confusion based on the controller’s unhelpful response forcing you to take matters into your own hands. Heck, bio needs; you’re going to burst if you don’t get down now.

2. Cancel IFR: If weather conditions permit, quickly cancel and then continue straight in.

3. Request straight in: This is basically a different question from the one you actually asked. Instead of asking if the controller expects you to fly the hold, ask for a straight in approach. (If he declines, at least you know to fly the HILPT. Or be ready with number 1. or 2.—and ask for a number to call.)

While this might sound like an edge case, flying is full of confusing points like this and it’s critical that you and the controller be on the same page.

You guessed right. Philip Mandel was the instructor in this story. He is grateful for students who cut him some slack when unexpected or confusing events happen during flight. Clearly, everybody learns from events like this.