You got a visual approach on your arrival this morning. You even canceled IFR ten miles out, and enjoyed a pleasant VFR ride to the runway. Now the AWOS is reporting low ceilings and two miles of visibility, requiring an IFR departure clearance. You’re a damp mess as you preflight, thanks to the drizzle drifting out of the saturated low ceiling.

And it’s not even the weather that’s actually bothering you. Every other IFR airport you’ve used had a control tower. You knew what to do: your clearance came from clearance delivery, taxi guidance from ground control, and takeoff clearance from tower. Now at this nontowered airport, you’re on your own. You’ve reviewed the regs and talked to some other pilots but studying it and flying it are no more the same than sex education and sex.

Like all ATC procedures, the phraseology air traffic controllers use for nontowered fields is designed to keep traffic flowing safely and in an orderly fashion. It will be different than what you’re used to, but not necessarily more difficult. You grit your teeth and tell yourself it’s time to take off the training wheels. You fire up the engine, do your runup, run your checklists and start taxiing to the runway.

Requesting Release

Some nontowered airports have their own clearance delivery frequency that allows you to speak directly to the radar controller. Be aware that you’re just one of many frequencies that controller works. Aircraft in the air will have priority over aircraft sitting safely on the ground. Be patient if ATC is busy.

Other fields require you to contact flight service and have them call the radar facility themselves via one of their landlines. No matter how you to talk to ATC, you cannot depart on an IFR clearance until ATC gives you a release.

What is a release? It’s permission for you to enter a controller’s area of jurisdiction. When a tower controller clears you for takeoff, he’s giving you access to his runway. When a radar controller issues you a release from a non-towered field, he’s granting you permission to enter his airspace while IFR.

ATC is legally responsible for separating you—as an IFR flight—from traffic and obstacles with 1000 feet and either three miles or five miles of separation between each IFR aircraft, depending on whether the controlling facility is an approach control or en route center, respectively. If you depart at some random time, the controller cannot ensure that there won’t be other traffic in your way. Hence the need for a release.

Go to the Head of the Line

As you reach the runway, you call for your clearance. To avoid confusion, make sure to state you’re calling from the ground at a specific airport. “N3AB, on the ground at Chester County, requesting clearance to Danbury.” The controller issues your IFR clearance and a heading to fly when entering controlled airspace. You read it back.

“Read back correct, N3AB” he says. So far, it’s all routine. Now he adds some nontowered airport spice to it. “Advise when number one at the runway. Hold for release.”

First, why does he care if you’re “number one”? Non-towered airports pose a huge burning question: how long will it be before you’re ready for takeoff? Controllers base their decisions on certainties as mandated in FAA Order 7110.65, the ATC rulebook. Chapter 3’s first line is: “Provide airport traffic control service based only upon observed or known traffic and airport conditions.”

Radar controllers can’t look out a window to see your position. In this case, you’re ready to takeoff but you could have been calling from a handheld radio on an FBO couch, nursing a coffee while waiting for your passengers or cargo. To nail things down, controllers have to establish your actual readiness.

“N3AB is number one,” you report, “and holding for release.”

Now your readiness is a “known” factor to ATC. The controller can bet that when he lets you depart, you’ll be on his radar scope within a couple of minutes.

A Grip on the Situation

“Roger, you’re number one, N3AB,” the controller replies. “Hold for release. Traffic is a King Air on four mile final. Expect a five minute delay.”

You acknowledge it. “N3AB, holding for release.”

he King Air’s on four mile final. You could easily take off before he gets anywhere near the airport. Why is ATC making you hold on the ground? The controller is providing appropriate separation between IFR airplanes.

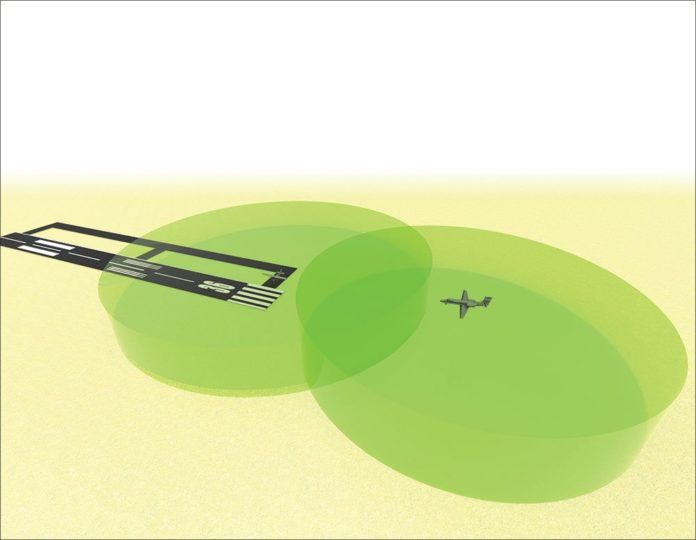

Remember that three mile or five mile separation I talked about before? When you’re released, that separation restriction becomes a bubble around your airplane. Since your airplane happens to be located on an airport, that bubble encompasses the field too. No other IFR traffic can enter or leave until you—plus your mighty bubble—depart the airport’s vicinity.

On a towered field, ATC can run IFR flights closer than three miles because tower controllers can look out the window and visually separate planes. Radar controllers don’t have that luxury for nontowered fields and need that radar separation.

If you’re released immediately, you’d depart on the mile-long runway. As the King Air hits a half mile final, you tag up on the radar scope a half mile upwind. That’s only two miles of separation, and therefore an ATC operational error.

The problem is more obvious with departures. If ATC releases two IFR departures off the same airport, the second guy could be snapping at the tail of the first. The controller has not ensured three miles of separation and, once again, faces an operational error.

This is why “hold for release” exists. It lets you know that ATC is unable to provide appropriate separation for you just yet. It may seem like an inconvenience at times, but the skies would be far more dangerous without it.

Of course, as AIM 5-2-6(a)(2) points out, there are also other reasons you might be held: “ATC may issue ‘hold for release’ instructions in a clearance to delay an aircraft’s departure for traffic management reasons (i.e., weather, traffic volume, etc.).” The overarching reasons—as with all ATC operations—are order and safety.

Into the Void

The King Air lands and courteously cancels IFR as he turns off the runway. The controller acknowledges the cancellation, eliminating the King Air’s own “bubble.”

Now it’s your turn. “N3AB, Approach, you are released. Clearance void if not off by 1210. If not off by 1210, advise me no later than 1215 of intentions. Time 1205.”

Great. You’re released, but it came with a lot of unfamiliar restrictions.

Think of the clearance “Void If Not Off By” time, or VIFNO, as Cinderella’s midnight. In 5-2-6 the AIM says, “A pilot may receive a clearance, when operating from an airport without a control tower, which contains a provision for the clearance to be void if not airborne by a specific time.”

“If not off by 1210, advise me no later than 1215 of intentions.” Again, AIM 5-2-6: “A pilot who does not depart prior to the clearance void time must advise ATC as soon as possible of their intentions. ATC will normally advise the pilot of the time allotted to notify ATC that the aircraft did not depart prior to the clearance void time. This time cannot exceed 30 minutes.”

What happens if you don’t check in? “Failure of an aircraft to contact ATC within 30 minutes after the clearance void time will result in the aircraft being considered overdue and search and rescue procedures initiated.” That’s right. You’re considered a possible downed aircraft and the authorities get called.

Please don’t go there.

Why have a void time at all? The first note attached to AIM 5-2-6 merely reinforces what we discussed in holding for release: “Other IFR traffic for the airport where the clearance is issued is suspended until the aircraft has contacted ATC or until 30 minutes after the clearance void time or 30 minutes after the clearance release time if no clearance void time is issued.”

Once again, controllers like absolutes. We also like to keep traffic moving. While a release opens the departure window, it can’t stay open indefinitely. The void time, or—as the last line of the note says—the 30 minute mark if no void time was given, provides a finite closing point around which we can base other traffic flow decisions. If you’re not getting out in a timely fashion, we shouldn’t have to delay other pilots.

Don’t fudge the void time either, as AIM 5-2-6’s second note warns: “Pilots who depart at or after their clearance void time are not afforded IFR separation and may be in violation of 14 CFR Section 91.173 which requires that pilots receive an appropriate ATC clearance before operating IFR in controlled airspace.”

Since your “appropriate ATC clearance” expires at the void time, you could face a pilot deviation. Plus, since you’re no longer “afforded IFR separation” by ATC, you could cause a traffic conflict, or worse.

The last thing the controller says—”Time 1205.”—is a time check to make sure your clock is synchronized with his and everybody’s on the same page.

Leaving Uncertainty Behind

Considering you’re at the runway and ready to go, you won’t be missing your void time.

“Roger, N3AB is released,” you reply. “Clearance void if not off by 1210. If not off by then, I’ll advise my intentions no later than 1215.”

With that, you change to the local advisory frequency—this is a nontowered airport, after all—and announce to anyone listening that you’re taking off. A couple minutes later, you’re punching through the overcast. The warm afternoon sun starts drying out your drizzle-dampened clothes. You change to the assigned departure frequency and check in with the controller as you turn towards the heading assigned during your clearance.

“N3AB, Approach. Ident.” You do so. It’s the same controller you just spoke to on the ground. “Radar contact. Altimeter 29.87. Climb and maintain 7000. Proceed on course.” And that’s that. You’re on your way.

Flying IFR in and out of nontowered fields isn’t overly complicated. It just requires more patience and teamwork between ATC and pilots. Separation options are simply more limited without a control tower crew keeping eyes on the traffic.

You, as the pilot, have the added responsibilities of making a finite release window and being timely about communicating with ATC. And remember that it’s not just controllers depending on you. It’s also your fellow pilots who are waiting to use the airport you’re vacating.

Extreme Opposites

What would it be like to fly from an uncontrolled field to one of the big airports like Dallas-Fort Worth, Atlanta or Los Angeles?

When flying to Class Bravo airports, you’ll often run into traffic management programs. Large airports have a large volume of traffic, so the ATC System Command Center wants to make sure all of those airplanes don’t arrive there at once. To alleviate congestion, they implement two different flow programs for those facilities: Expect Departure Clearance Time (EDCT) and Call for Release (CFR).

Both methods end up with the same result: you are not allowed to depart until a specific time window. It’s a way of slotting you into the flow of other traffic arriving at those airports. Where the programs differ is in how that time is determined.

EDCTs are computer-generated based on your proposed time. You can check if you have an EDCT at http://www.fly.faa.gov/edct. Otherwise, when you receive your clearance, the controller should have it available attached to your flight plan. If you are assigned an EDCT, ATC can release you between five minutes before and five minutes after the time. For example, if your EDCT is 1215Z, the departure window is between 1210Z and 1220Z.

Call for release, on the other hand, requires manual coordination between your controller and traffic management unit (TMU) personnel in the overlying en route center. When you get your clearance, the controller should be aware of any CFR programs for your destination. If there is one, he’ll ask you at what time you’ll be ready to take off. He’ll then call TMU and they’ll issue you a release window based on the time you gave, typically between two to five minutes in length.

Whether you’re working with an EDCT or CFR window, all we controllers ask is that you be ready to go when the time comes. Not meeting those windows can result in significant delays for you. If you are unable to make it, advise us as soon as possible so we can coordinate a new window for you. —TK.

Tarrance Kramer doesn’t discriminate between airports. Towered, nontowered, if it’s got a runway, he’ll work with it.