Some time ago we published a letter from a pilot who complained that ATC regularly vectored her toward mountains that rise over 4000 feet just 11 miles southwest of KAVL in Asheville, NC. Her single-engine airplane would wind up level with the ridgetops. Requests for a safer southerly route around the mountains were always denied. Upon request, ATC would vector her on course once they realized she was flirting with cumulogranite.

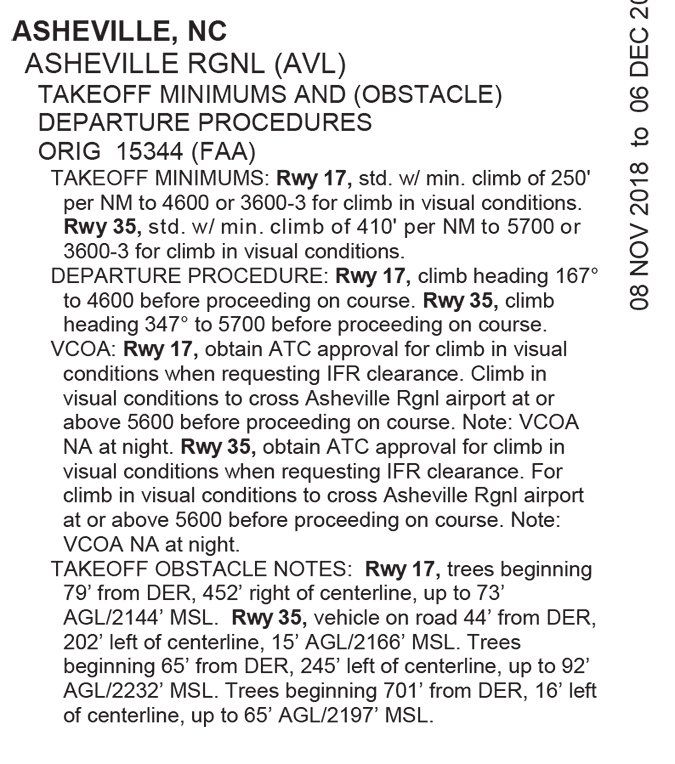

Then she discovered two Obstacle Departure Procedures (ODPs) at Asheville, one per runway end. She wrote us saying “these were not emphasized during my training.” She is not alone in not having learned much about departures.

Teaching all the various types of departure procedures (DPs) is a very difficult part of a complete IFR curriculum, because the needed tools are not readily available. SIDs cannot be flown without ATC permission, and typically only exist out of larger airports where a student might not wish to go. Students quickly forget about ODPs buried in the approach book. Older GPS navigators often lack memory space for SIDs and STARs, as do some desktop emulators/trainers.

The instructor’s best tools are classroom instruction and articles like this. I’ll focus on departure procedures designed primarily for obstacle avoidance. SIDs, on the other hand, are designed not only to avoid obstacles, but add a lot of ATC convenience.

The Radar Departure

You might think you outsmarted ATC by writing “No SIDs” in the Remarks section. Instead they assign you a radar departure. Gotcha! What’s a radar departure?

Frequently employed in congested areas, you can expect navigational guidance by radar vector. If you will be vectored immediately after takeoff, you’ll be given the initial heading to fly as part of your takeoff clearance. This covers you and ATC in case radio contact is lost during departure.

There is nothing special about beginning a radar departure. Contact Departure Control when instructed by Tower with the standard: your aircraft number, your current and target altitude, and any other restrictions (speed, crossing, etc.). This allows ATC to verify your Mode C altitude readout. If you’re on an assigned heading, mention that, too.

ATC will identify you and issue “Radar Contact.” Being in radar contact does almost nothing for you. ATC isn’t responsible for your terrain and obstacle clearance until that first vector, which also makes them responsible for coordinating your flight with other controllers, such as Tower with Departure. ATC will take you by the hand and give you headings, altitudes, and possibly restrictions to move you out of the dense terminal airspace into the en-route portion of your flight. Contrary to usual practice, do not expect to be given a purpose for a vector since its intent is obvious.

Promptly comply with headings and altitudes as assigned. This is busy airspace where even an undue delay of a few seconds can cause issues. But do not devolve into an automaton. As PIC, keep your situational awareness, know where you are and where you’re being sent, and question any heading or altitude if you believe it’s incorrect or would cause you to violate a regulation. Advise ATC immediately and let them revise your clearance.

Wiht each call from ATC, you’ll get a handoff to another controller, different or more instructions and/or restrictions, or, finally, a clearance to join your planned route. That clearance could take the form of a vector to intercept a leg you’d planned, or could simply be a clearance direct to an upcoming fix on your route. In either case, comply with the instruction knowing that you’re likely done with the radar departure.

A radar departure is a time when you want to be at peak situational awareness. If radar contact is lost, expect to supply position reports so ATC can track you.

Before takeoff, be ready to navigate as dictated by your clearance with nav receivers and GPS set and checked. As ATC vectors you, let your instruments help you maintain SA relative to your cleared route.

Nontower Airport Departures

A radar departure can be issued from a nontowered airport or when the tower is closed. One way is to depart VFR and request your clearance once airborne. Occasionally you can reach FSS or ATC on the ground. Some airports have licensed UNICOM operators who can contact ATC and relay your clearance. Another way is to call FSS or the IFR Clearance Delivery hotline at (888) 766-8267. Your airport might have a remote communications outlet that patches your VHF radio into the telephone network to FSS.

RCO information is listed on airport charts and instrument approach charts with other communications frequencies. Signs are often on an airport to give you frequency and usage instructions. Best of all, some airports have a clearance delivery frequency on the field, noted in the Chart Supplement under Communications.

If you call, expect a void time: “Clearance void if not off by 1030.” You can depart within that period and fly the issued clearance. If you do not depart, inform ATC within 30 minutes of your void time or your reserved IFR space will be released for other traffic.

Lacking specific departure instructions, proceed on course as discussed below. Sometimes departure instructions will be issued as, “Upon entering controlled airspace, fly heading 280, climb and maintain 4000,” to get you started. This bit of legalese is because ATC has no authority or responsibility outside controlled airspace.

You might be given a radar departure if the airport lacks a DP or ODP or you have requested “No SIDs.” Airports without an approach do not have DPs. It could be that you cannot comply with a DP, perhaps due to a steeper climb gradient than you can manage, or to an altitude beyond your reach. Maybe there is no DP suitable for your desired route.

Even if you were never introduced to radar departures, they are surely the easiest departure a pilot could request or be assigned.

Visual Climb Over Airport

If the weather is VMC, an IFR aircraft can fly a climbing spiral over the airport to a specified “climb-to” altitude from which the instrument portion of the flight can begin. A VCOA is designed when obstacles more than 3 SM from an airport require a climb gradient greater than 200 feet per NM (FPNM).

VCOAs are published in Section L, the Take-Off Minimums and (Obstacle) Procedures section of the AIS (FAA) approach booklet. Before departure, notify ATC before executing the VCOA or they will wonder what you’re doing. As always, you must have a clearance before entering IMC.

Refreshing the ODP

All DPs provide obstacle clearance if the aircraft crosses the end of the runway at least 35 feet AGL, climbs to 400 feet above airport elevation before turning, and climbs at least 200 FPNM unless a higher climb gradient is specified. Every ODP is designed to use the most efficient path to the en-route structure or to help you climb to an altitude where you can proceed in any direction. With but one ODP per runway, it becomes the default IFR departure procedure instead of a SID or alternate route concocted by ATC.

An ODP may be flown without ATC clearance unless necessary to maintain aircraft separation. Often towers and TRACONs are unaware of ODPs because they need not be filed in a flight plan and are flown at the pilot’s discretion.

Even so, if the ODP is textual, enter something like “will depart KXYZ airport Runway 3 via textual ODP” in your instrument flight plan’s remarks section or simply mention your intent when reading back your clearance. A graphic ODP may be filed in the remarks section using the computer code in the procedure’s title, e.g., HKY3.HKY for the HICKORY THREE DEPARTURE (OBSTACLE). This helps controllers understand your intentions. Regardless of how you do it, assure that ATC knows you’re on the ODP to prevent surprises.

ODPs are textual by nature, but some are intricate enough to justify a graphical chart. Such charts include the word “(OBSTACLE)” in the title as above. All RNAV ODPs are issued graphically. ODPs, along with the VCOAs, are also found in Section L of TPP approach chart booklets under the heading Takeoff Minimums (Obstacle) Departure Procedures. Procedures are listed alphabetically by city and state. Look for a very cryptic note if a graphic chart is in the main body of the booklet. At Hickory Regional (KHKY) it simply says, “DEPARTURE PROCEDURE: Use HICKORY DEPARTURE.” The Index (Section K) notes it as, “DPS … HICKORY THREE (OBSTACLE) … [page] 385.”

When possible, pilots are strongly encouraged to file and fly a DP at night, during marginal visual meteorological conditions, and of course in IMC.

No ODP?

You landed at an unfamiliar nontowered airport. The weather is 400 overcast in two miles’ visibility. There is no way to know if an obstacle lies near you on departure. Has the FAA abandoned you to your fate?

Not at all. When building an instrument approach, FAA procedure designers (known colloquially as “TERPSters”) appraise the need for a formal DP, either a SID or an ODP. If a departing aircraft can turn in any direction within the Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS) defined assessment area while remaining clear of obstacles, then it passes the diverse departure (as in “depart in any direction you like”) test and obviates the need for an ODP.

Operationally, lacking a DP and no note stating that a diverse departure is not authorized, you can safely depart by maintaining runway heading (mind the drift), climbing with a 200 FPNM gradient or better to 400 feet above runway elevation. Continuing your climb, turn in the shortest direction to your first filed point and you are on your way. Once vectored off an ODP or a SID, as onto an airway, you can consider the DP canceled.

It’s awkward that diverse departures are allowed by the absence of a note; the FAA is telling you something without actually telling you. At one time the FAA considered adding a note on the approach chart to indicate that a diverse departure was an option, but it never happened. Go figure.

Back to Asheville

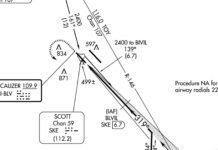

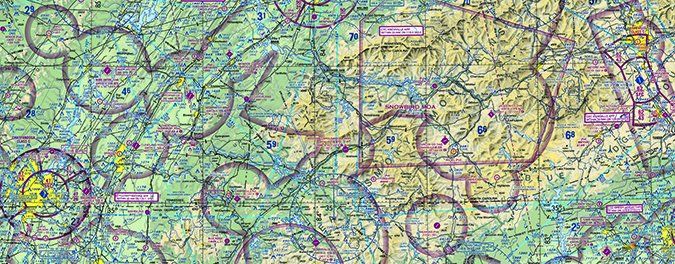

Our pilot’s destination was KCHA in Chattanooga, TN. A typical route is KAVL-HRS-GQO-KCHA. The first leg of the flight is shown (green) toward the Harris VOR (HRS). The direct route (red) quickly enters higher terrain.

KAVL has three departure types. She could fly the Asheville Five Departure with the Harris transition provided her airplane can manage the higher-than-normal gradients, especially departing Runway 35.

Her second option would be to fly an ODP. Departing Runway 17, it specifies flying straight-out to 4600 feet before proceeding on course. Departing Runway 35, it’s straight-out to 5700 feet before turning. No wonder she’s happy.

Third, she could fly the VCOA for either runway to 5600 feet before proceeding on course. This option is a little less desirable than the alternatives because time and fuel are spent going nowhere but up, VMC is required and the VCOA is not authorized at night. Oh, and it might conflict with other plans ATC has.

Departure Planning Roundup

Contemplating your departure, consider the terrain and obstructions near the airport. Our intrepid pilot got her ODP, but it requires her to fly over a “remote, wooded wilderness without any hope of survival if I lost power.” Can you clear obstacles visually? If not, a DP is in order. Regardless, research whether an ODP or SID is available for the departure airport. If not, find another way to depart safely.

Some years ago, we recounted the tragic case of a pilot who departed a Vermont airport to the south. Had he followed the DP he would have turned right. Instead he turned left directly into a mountain. ‘Nuff said.

Fred Simonds, CFII, is allergic to cumulogranite. He lives in Florida where there is none. Instead they have lots of tall towers. See his web page at www.fredonflying.com.