While many of the regulations that govern our actions are clear, there are a large number that may seem vague or even leave room for unintended interpretations. For these reasons, it is possible to seek official and binding interpretations from FAA’s legal department, either through a direct request or possibly more onerous encounters with the regulations.

Recently the FAA posted legal interpretations and Chief Counsel’s opinions on their web site. You can find them by searching “FAA legal interpretations.”

Sections 91.167, Fuel Requirements; 91.175, Takeoff and Landing; and 91.185 on communications failures generated the most correspondence, making them worth a closer look. The interpretations can also offer some insight into how the FAA attorneys think.

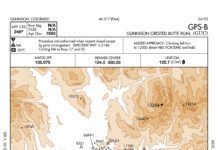

91.167: Fuel Requirements

A retired Air Force colonel asked if 91.167 requires a pilot to have sufficient fuel to attempt an approach at the destination airport, fly to the alternate and have 45 minutes of fuel remaining once there. He sought to clarify whether fuel for an approach and miss is required at the destination because 91.167 says only that the aircraft must have enough fuel “to complete the flight to the first airport of intended landing.”

The rule says nothing about “attempting” an approach or landing. The FAA counsel held that a pilot who fuels the aircraft “with only enough fuel to ‘attempt an approach’ would fall short of the regulatory requirement. The pilot must consider fuel needed for an approach and it is presumed that the pilot will land at the destination if able. Obviously the plane will not land at both airports, but the missed approach fuel used in attempting to land at the destination equals, for the purposes of this rule, fuel to land the airplane.”

The FAA further reasoned that marginal weather can change rapidly. A pilot might start an approach at the destination with adequate weather, but if the weather changes, a missed approach can be required, followed by diversion to the alternate.

A pilot experiencing fuel exhaustion prior to reaching either airport or who declares an emergency for an expedited landing due to low fuel could be found to have operated the aircraft in a careless or reckless manner and be violated under 91.13. Smart pilots would land short for fuel and avoid 91.13 altogether.

Another pilot’s inquiry revealed another way to violate 91.13. Section 91.103(a) requires a PIC to become familiar with “all information concerning that flight.” Though no specific mention regarding fuel is made, “Failure to correctly interpret or translate [such information] into the correct amount of fuel required for flying time can constitute careless operation of an aircraft and therefore be a violation of 91.13.” This particular interpretation stemmed from a case where the “pilot did not determine the fuel on board prior to departure despite knowing of potential air traffic delays along his route.”

One question asked what rate of fuel consumption to use when calculating the 45-minute reserve requirement. The FAA restated 91.167(a)(3): fuel consumption should be calculated at normal cruise speed.

Then the FAA went further. “The operator’s data must be accurate and verifiable no matter the rate of fuel consumption the operator uses.” On a recent IFR cross-country, we used 31 gallons over 4.1 hours of Hobbs time, equaling 7.5 gph but the book said it would use 7.4. Actual calculations trump book numbers, and it’s wise to track fuel consumption in any aircraft you fly regularly. Hard numbers help you comply with the regs because you can prove empirically that the numbers are accurate.

A pilot asked when it would be legal to continue to the destination when it is no longer possible to reach the alternate and land within 45 minutes.

Perhaps demonstrating restraint, the FAA replied that the pilot is always responsible, citing 91.3 and 91.103. The right and legal move is to land short of destination and refuel. Otherwise, if the pilot attempts a landing and wastes fuel that could be used toward going to the alternate, that’s illegal, too.

If a pilot gets into the 45-minute fuel reserve, must they declare an emergency? No. The FAA’s guidance is to declare a fuel emergency when in the pilot’s judgment it is necessary to proceed directly to the airport at which (s)he intends to land.

If you advise ATC of “minimum fuel,” have you violated 91.167? Again, no. The FAA defines “minimum fuel” to mean that “an aircraft’s fuel supply has reached a state where, upon reaching the destination, it can accept little or no delay. This is not an emergency situation but merely indicates an emergency situation is possible should any undue delay occur.”

91.175: Takeoff and Landing

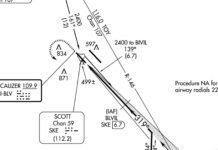

A letter from the Airline Pilots Association asked if executing a full approach under IFR in a non-radar environment was necessary. The FAA responded that 91.175(a) calls for a standard approach under Part 97. Absent radar, an approach must begin at a published IAF. Flying the full approach is the only way to ensure safe descent gradients, communication and obstruction clearance. This is why you can’t fly yourself to an Intermediate or Final Approach Fix without radar.

ALPA further asked if flying a DME arc initial approach segment could be substituted for a published IAF along any portion of the arc. FAA said no, adding that if a feeder route to an IAF is part of the published procedure, it is considered a mandatory part of the approach.

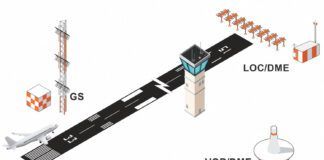

An intelligent questioner asked whether the visual approach slope indicator referenced in 91.175(c)(3)(vi) is limited to VASI systems or whether it includes PAPI, tri-color or pulsating VASIs, or alignment of elements. The FAA answered that the term VASI now refers not just to a specific system but to all the above. For you airline types, this also holds regarding 121.651.

A Colorado writer complained that the Aspen tower would routinely offer the Lindz 3 departure procedure and takeoff clearances when the weather was below SID-specified minimums. The FAA found no fault with the tower because they simply separate traffic; the pilot is responsible for complying with weather requirements for operation of aircraft. This subtle distinction is worth remembering. In fact, on a recent flight our editor was cleared for a visual approach after sighting the preceding aircraft, but he didn’t yet have sufficient cloud clearance and had to decline the visual approach clearance. Moral: the pilot is solely responsible to meet weather minimums.

A Darwinesque pilot asked if they could accept an ATC clearance for a SID or ODP with a nonstandard climb gradient knowing the aircraft couldn’t meet the specified climb gradient if an engine fails on takeoff.

The interpretation includes all operators via the AIM regardless of the part under which the flight is conducted. Paragraph 5-2-8(b)(2) says that “Development of contingency procedures, required to cover the case of an engine failure or other emergency in flight that may occur after liftoff, is the responsibility of the operator.” The AIM is not regulatory, but it is authoritative and has the de facto effect of law.

A pilot from Virginia asked whether a pilot may operate an aircraft below a published DH/DA or MDA if the pilot has the runway in sight but the runway visual range or RVR is reported at less than the published RVR for the approach.

The FAA attorney said, “One of the conditions [of 91.175] is that the ‘flight visibility is not less than the visibility prescribed in the standard instrument approach being used.’ Another condition is that one of the visual references in the runway environment listed in the rule must be visible to the pilot under 91.175(c)(3)(i)-(x).”

“Controlling visibility is not ground visibility, as reflected by the RVR values, but rather flight visibility as measured from the cockpit of the aircraft.” In this case, the pilot has the runway in sight. “Accordingly, the pilot may continue the approach below the authorized DA/DH or MDA because the pilot has determined the flight visibility and the runway, one of the enumerated references in 91.175(c)(3) is in sight. The pilot must maintain this flight visibility from descent below MDA or DA/DH until touchdown.”

A follow-up letter from the same writer asked for yet another interpretation of 91.175(c). Here he asked whether a pilot can descend below 100 feet above the touchdown zone elevation and land during an instrument approach if the flight visibility is less than that prescribed in the approach being used.

The FAA answered that a pilot conducting an instrument approach may not operate an aircraft below DA, DH or MDA unless three requirements are met.

First, the aircraft must be “continuously in a position from which a descent or landing on the intended runway can be made at a normal rate of descent using normal maneuvers, per 91.175(c)(1).” Second, “the flight visibility [may not be] less than the visibility prescribed in the approach being used” per 91.175(c)(2). Third, “certain visual references in the runway environment must be ‘distinctly visible and identifiable to the pilot’ per 91.175(c)(3) (i)-(x).”

In his scenario, the pilot was using the approach lights as a runway-environment reference and asked if the pilot could continue to descend if the flight visibility fell below the published value. By that measure, the second condition would not be met, and if the approach lights fell out of sight as the aircraft flew over them, neither would the third.

91.185 Communications Failure

Several writers picked up on a huge hole in 91.185: It makes no reference to STARs, only approaches. FAA lawyers could not answer STAR-related questions because there is no rule to reference and there are no STARs as far as 91.185 is concerned. The only guidance the FAA could offer was to “commence descent in accordance with either one of the two paragraphs as appropriate.”

For example, one pilot asked, “In cruise flight, your communications fail. Can you begin descent on an arrival containing crossing restrictions?”

The FAA can only answer using 91.185(c): If the cruising altitude is the highest of the MEA, the last assigned or last expected altitude, then that’s what you use for that route segment, “notwithstanding that the intended arrival may contain mandatory crossing restrictions.” The nugget in this response is that 91.185 supersedes any crossing restriction(s), which is tantamount to saying STARs are meaningless in lost communications.

Of course, when you experience radio failure could change the answer. If your radios go up in smoke after you’ve been told to descend via the arrival, you’ve already received what constitutes real and expected altitude assignments with which you should comply, although this is our interpretation and doesn’t come from the FAA.

Another pilot posed a question he could have answered himself: Flight 123 receives a pre-departure clearance: “November 123 cleared to KXYZ airport as filed, climb and maintain five thousand, expect one-zero thousand 10 minutes after departure…”

After departure and receiving clearance to ten thousand feet, the flight loses radio communication in IMC and continues under 91.185. Nearing the destination, the pilot notices that (s)he is 25 minutes earlier than their planned ETA.

The writer contends that 91.185 permits the pilot to “begin an instrument approach into the destination airport and land regardless of the early arrival because the airport was given as a clearance limit in the initial ATC clearance.”

The FAA disagreed. Citing 91.185(c)(3), “When the clearance limit is not a fix from which an approach begins, and given no EFC time, the pilot would proceed to the destination airport and upon arrival over it, proceed to a fix from which an approach begins. The pilot would then commence descent and approach as close as possible to the ETA. Should the pilot arrive over the approach fix earlier than the ETA, the pilot would need to hold at the approach fix until such time and commence descent and approach as close as possible to the ETA.”

Another pilot asks for clarification as to whether the holding fix and clearance limit are the same place. The FAA answered, “Not necessarily. The AIM defines a clearance limit as the fix, point or location to which an aircraft is cleared when issued an ATC clearance. If ATC clears a pilot to the airport, the airport becomes the clearance limit. Therefore, a clearance limit, by definition, can be any fix, including a holding fix, but is not necessarily one.”

This writer also asked if 91.185(c) applies if no holding instructions have been given. The FAA answered “Yes. There is nothing to indicate that 91.185(c) would not apply if no holding instructions have been issued.” The section defines holding at a clearance limit fix where an approach begins and also one where an approach does not begin.

In a telling question, the writer thirdly asked how an aircraft without GPS would comply with holding as above. The FAA counsel replied that the flight should be planned using navigation equipment aboard, available ground-based navaids, and that “ATC will not place the pilot on a route using navaids unavailable to the aircraft.” They failed to note, however, that ATC largely presumes that most aircraft have GPS, even if filed /A.

Last, an off-the-wall question: Does ATC want pilots to postpone their descents when NORDO? The answer is plain as day in 91.185(c)(3)(i)(ii). Begin descent at either EFC time if one has been given or ETA if one has not.

Section 61.57 deals with recent flight experience. The FAA legal team offers definitive answers to that perennial question, “Who’s PIC?” We’ll get to that next time.

Fred Simonds, an active CFII in Florida, tries valiantly to comply with all 700 regulations. See his web page at www.fredonflying.com.