The trusty digital timer is a fixture in IFR training. You learned to time your turns, your flight segments, holds and approaches. You learned to keep an eye on your arrival times, lest you run late and need to inform ATC.

Lately, though, the practice of timing approaches and related operations has largely gone by the wayside with the use of GPS navigators. With your flight plan laid out and the ETA for each upcoming fix displayed nicely on your screen, few pilots bother to separately use a timer. And, let’s face it: Timer use for navigation is solely a backup if you’ve got GPS and a moving map.

Backups, however, are important. Ask anybody who ever lost GPS (or the satellites) in the muck. It happens. Besides, why else would you have two radios? So, mundane or not, we should keep the habit of timing both enroute and on approach, especially when using a localizer or a VOR in instrument conditions. This has the added advantage of keeping us engaged rather than simply being a systems monitor. Plus, there are other needs for keeping an accurate timer that you should still be meeting.

Timing Basics

Recall that a clock is required equipment. Most of us use whatever is on the panel or maybe get a general-purpose digital timer like those reviewed in “It’s Just a Timer” in the December 2014 issue of IFR.

You should track your enroute segment times, comparing them with your flight plan. Why? For one thing, it’ll be an early warning for unforecast winds—which are an early warning of unforecast weather. It’ll also keep you monitoring your fuel, lest you suddenly find yourself with 19 minutes of fuel for 20 minutes of flight, especially for a diversion.

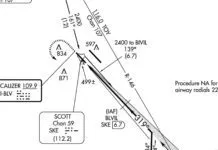

Before GPS, timing was essential for monitoring our position during the segments of an instrument approach. For example, take the VOR Runway 13 approach at Marshall County, Illinois (C75)—a traditional approach with the standard procedure turn. Assume you don’t have DME and you’re coming from the east to the initial approach fix, the Bradford VOR. You’ll cross the navaid, fly the 313-degree radial and run the timer for one minute, which is the default for no-wind condtions.

Since there’s always wind, we’ll adjust accordingly. If you’re thinking you’ve got a 30-knot tailwind while flying 120 KIAS, 25 to 30 seconds will be enough before the course reversal. (Remember, you’re not going for an exact distance here. You just need enough distance to complete your procedure turn and get lined up on final before the FAF while remaining within the protected airspace.)

Start your procedure turn and time your outbound leg for a minute, adjusting for wind. Fly the procedure turn inbound and intercept the final course. Here, you don’t need to time as you’re just waiting to intercept, but it doesn’t hurt if you do. (In fact, our editor always times the inbound leg because it’s one more check to make sure he doesn’t fly through final—or at least recognize when he has.) Make your way to VAVAR, the final approach fix. Many of us were trained to remember the “Three Ts” at the FAF: Time, Throttle, Talk. Start the timer, throttle back to descend, report your position.

Here’s the fun part. The timing table shows that at 120 knots, your time to fly the 5.2 nm from the FAF to the missed approach point is 2:36. Of course, it uses groundspeed, so we account for the wind. With a 20-knot headwind, plan about 3:05. When the time is up, land or miss, depending on what you (don’t) see.

If you miss and head to the Bradford VOR to hold, you’ll need to—you guessed it—time your entry since it’s not a direct entry. This hold has a parallel entry, so use the one-minute standard adjusted for wind to fly outbound on the parallel, then turn left back to the fix.

In the holding pattern, adjust your outbound time for a one-minute inbound leg. These are non-precision operations, but you still should get as close as possible to the desired times. As with estimating wind speed and direction, hitting this stuff on the mark takes practice.

Do I Have To?

So what if you do have a DME, which eliminates the need for timing, plus a portable GPS of some kind for, uh, “situational awareness”? Using our VOR 13 example, which allows for DME to mark our position, it’s perfectly acceptable to use distance instead of time in these cases. But why not use the timer for all approaches? It adds consistency, so we’re less likely to forget to time when we’re required to. Do the three Ts every time on final and you’ll never forget. It’s a lot like doing a GUMPS check on every flight, even when you’re in a fixed-gear airplane that day.

To sweeten the deal, think of timing as your backup should something go awry. You’ll want some idea of how long you’ve been flying the final leg if you look over and realize your DME receiver died and you’d really like to have a shot at landing before the unseen airport slides behind you.

It would be no fun to miss without knowing for sure how far beyond the MAP you’ve gone. If you’ve made a habit of flying your approaches on course at the proper airspeeds every time and get really good at correcting that time for wind, you’ll know your timer gives you an idea of where you are. If you figured you had two and a half minutes to see the airport and something breaks down at two minutes, you can be pretty sure you haven’t reached the MAP yet. If you didn’t realize you lost your navaid and three minutes have gone by, it’s time to take defensive action (pun fully intended).

This also applies to approaches without a final fix, such as VOR approaches that use a navaid on the airport. (Reminder: When the fix is on the field, your outbound time prior to course reveral is two minutes.) Once you’re established inbound, do the 3Ts. With your situational awareness powers, you already know how many miles you are from the MAP, right?

Perhaps you’re thinking you can fly RNAV approaches with far more precision, plus plenty of redundancy, so why bother? Again, it’s the easiest, cheapest insurance policy. You never know when you won’t get that RNAV approach, just like you never know when a satellite signal will decide to knock off for the night. So when you’re assigned a localizer approach because there is nothing else, you’ll want to be comfortable with timing.

Everything Else

With navigation and situational awareness uses out of the way, you should be timing other things. Most of these are good practice and you can’t substitute the GPS since that system, capable as it is, doesn’t quite yet know everything about your operations.

If you get an “expect further clearance…” or “expect 8000 in 2 minutes” from ATC, you can use a timer to remind you. Fuel-tank switching generally follows a time-based model, or you may want to be reminded to do a regular systems check; timers are your answer. Just remember what each one is timing.

On a descent that you want to make as gradual as possible because you’ve got a lot of distance to cover or you want to avoid rapid engine cooling, timing can supplement your power and speed settings. Engine cooling guidelines generally suggest one to two inches of power reduction maximum per minute. Better time that minute.

Ground operations can benefit as well. In the dead of winter, it doesn’t hurt to time an engine warmup along with watching the temperatures to ensure you’re not rushing through things. And cooling down for a minimum time after landing, particularly for turbochargers, is a good habit, with a three-minute delay at or near idle power being a typical guideline. You’d be surprised how long that can be if you’re not timing it.

Timers aren’t fancy equipment, but they do a lot to help us keep an eye on things. Better yet, they can save us mental bandwidth should a flight suddenly become more complicated. They’re still around and won’t go away soon. Just remember to push “Start.”

Elaine Kauh, is a CFII who flies and writes in eastern Wisconsin. She proudly shows off her 2004 West Bend 4-in-1 timer whenever she can.