Around 1980, the FAA tried using adjacent approach control facilities to manage traffic through or within major metropolitan areas. The practice was dubbed tower enroute control (TEC), also called Tower to Tower. But these names are misleading because pilots on TEC routes never talk to tower controllers while enroute. Go figure.

(The difference between TEC routes and other canned routes is that TEC routes never touch center airspace.)

The Air Traffic Control Handbook defines TEC: “the control of IFR enroute traffic within delegated airspace between two or more adjacent approach control facilities. This service is designed to expedite traffic and reduce control and pilot communication requirements.” A good idea; let’s see if there’s any “there” there.

TEC Talk

The FAA created a series of routes through selected TRACONs based on existing airways. Intended to be low-altitude overflow resources, TEC routes reduced busy center workload because TEC routes never penetrate center airspace.

TECs seem built-to-order for piston-GA aircraft: at and below 10,000 feet to stay within TRACON airspace; not intended for turbojets and great for flights under two hours. TEC routes do not scale up very well because longer flights might require excessive coordination across multiple TRACONs, resulting in delays.

When a major metropolitan airport experiences significant delays affecting TEC routes, pilots can land at a satellite airport near the major primary airport via the same or nearly same TEC routing.

With the best of intentions, the FAA planned to expand the TEC program to include as many facilities as possible applying mostly to nonturbojet aircraft flying at and below 10,000 feet. It didn’t quite work out that way.

It’s all About Execution

Intrigued by the above, I ran to my Southeast A/FD, and found—nothing. Preferred routes were listed. I briefly thought that TEC routes were commingled with preferred routes. But no, the FAA would never mix apples and oranges like that; TEC routes should have their own pages.

I then scoured the rest of the A/FD volumes and learned that there are only two areas in the U.S. with TEC routes: the Northeast and Southern California. Hmmm, no mention of that in the AIM.

Just to be sure, I downloaded the raw Excel TEC file from the FAA web page and searched all the TEC routes. Sure ’nuff, they’re all in the northeastern U.S. or Southern California. This is atypical of the FAA. If they do something of this nature, they generally do it nationally to benefit the entire pilot community. Not this time. I wondered why not.

TEC routes are found in the A/FD in the so-called “back pages” or supplemental material that follows airport information. If you’re working solely from a digital A/FD, you may struggle to get to those pages. Reading the textual description that precedes the TEC route listing, I learned that not only are TEC routes limited to the Northeast and Southern California, the way you file them in one region differs from the way TECs are filed in the other. I began to curse our editor for assigning me this project.

The AIM says that no unique pilot requirements are needed to use the TEC program. True, but other sources suggest that while TEC routes are generally more direct and have less restrictive separation requirements, they can be complex to fly. Analyze a TEC route you are considering and be comfortable that you can fly it before filing it. TEC routes are only available on a workload-permitting basis from an approach-control facility. As always, what you file may not be what you get.

The TEC concept has been applied sporadically in some areas. The AIM says “A few facilities have historically allowed turbojets to proceed between certain city pairs, such as Milwaukee and Chicago, via tower enroute and these locations may continue this service.” Or not, apparently, since no TEC routes are listed there.

Finally, the AIM adds that “Normal flight plan filing procedures will ensure proper flight plan processing. Pilots should include the acronym ‘TEC’ in the remarks section of the flight plan when requesting tower enroute control.” This is not quite accurate when filing in Southern California as we’ll see.

You can get a TEC clearance from a nontower airport. Simply file and request your clearance on the ground as you normally do. Although generally ill-advised, it’s even possible to request a TEC-route clearance from ATC once airborne.

Filing in the Northeast

As the diagrams show, dense numbers of TECs exist along the eastern seaboard extending south from Buffalo, Elmira and Binghamton, New York. At the southern end, Roanoke’s radar approach control area (RAPCON) is adjacent to the RAPCON serving Piedmont Triad Airport in Greensboro, NC (GSO) as the note indicates. RAPCONs in Cleveland and Akron (CAK) are adjacent to Erie and Pittsburgh as well. The A/FD adds that the diagrams are intended to show general geographic areas and that the route descriptions are the primary reference. Most TECs are within radar coverage.

The Northeast A/FD encourages pilots to make use of TEC routes, which are also available from FSS. Other seemingly shorter airways may take you into center airspace which can cause delays. TEC routes are canned routes that avoid conflicts in arrival and departure corridors.

Northeast Route Descriptions

The TEC route descriptions are in four columns, listed in alphabetic order by origination approach control. Next, the route is specified, followed by the highest altitude allowed and the general destination including satellite airports if any.

Permitted satellites for larger destinations are listed at the beginning of the table. If you file from the Albany Approach Control area, the route to Bridgeport, CT is from the Albany VOR via V44 to DENNA. After DENNA you could land at KBDR in Bridgeport, KHVN in New Haven, KOXC in Oxford, CT or 3B9 in Chester, CT. Satellite airports also appear in the route listing. Baltimore lists four satellites to the south and 13 to the north.

The route listing may contain further restrictions in parentheses, such as single engine and /E, /F, /G only or -180 knots only to denote a speed restriction. These are self-explanatory.

If you read DIRECT in the route listing, it means that radar vectors will be used or no airway exists as between Philadelphia (KPHL) and New York’s KJFK: PNE PNE090 ARD126 V16 DIXIE (Direct). About 20 routes are simply DIRECT. Importantly, DIRECT implies that a SID or STAR may be your future.

Should a NAVAID or intersection identifier such as ALB CTR PVD appear with no airway either before or after, the routing is understood to be direct unless ATC instructs otherwise.

A route that begins with an airway such as V14 V428 from Albany to Elmira, NY indicates that the airway more or less overflies the airport or that you will be radar vectored. ATC may require you to descend from 10,000 feet in order to remain in approach control airspace. They will vector you if the highest altitude they can give you is below the MEA.

If more than one route is shown to the same destination, take your pick. All routes are bidirectional unless otherwise noted.

Since TECs only exist during a terminal facility’s normal operating hours, be sure there is no effective NOTAM stating that the facility will be closed during your planned flight time.

Where would an FAA publication be without notes? If a note number in parentheses appears in a route, it denotes something about the aircraft that can fly it and the maximum speed at which the route can be flown. For instance, a (1) denotes single-engine only. A (3) means propeller-driven aircraft at speeds under 250 knots. These notes are important and their implementation is utterly different from the SoCal TEC listing as we’ll see.

Unlike Coded Departure Routes, and unlike the TEC routes specified in California, there are no route identifier codes for TEC routes in the Northeast.

Filing in Southern California

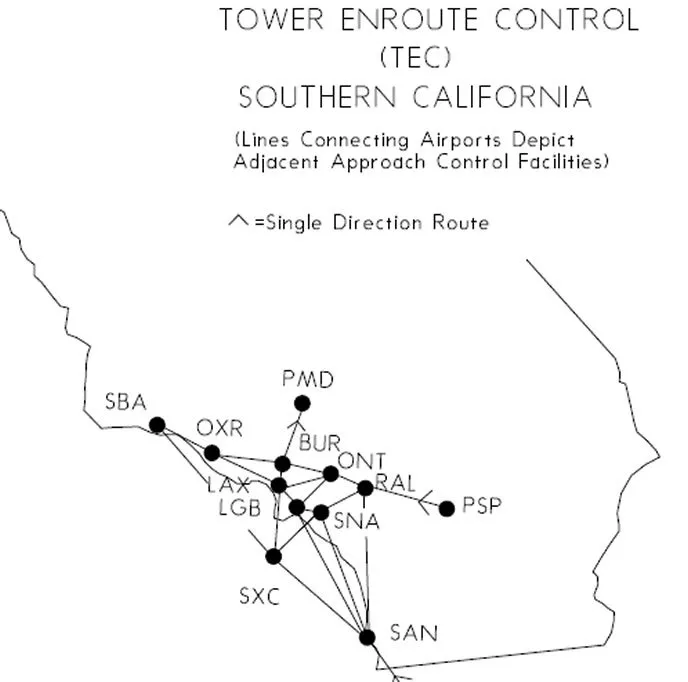

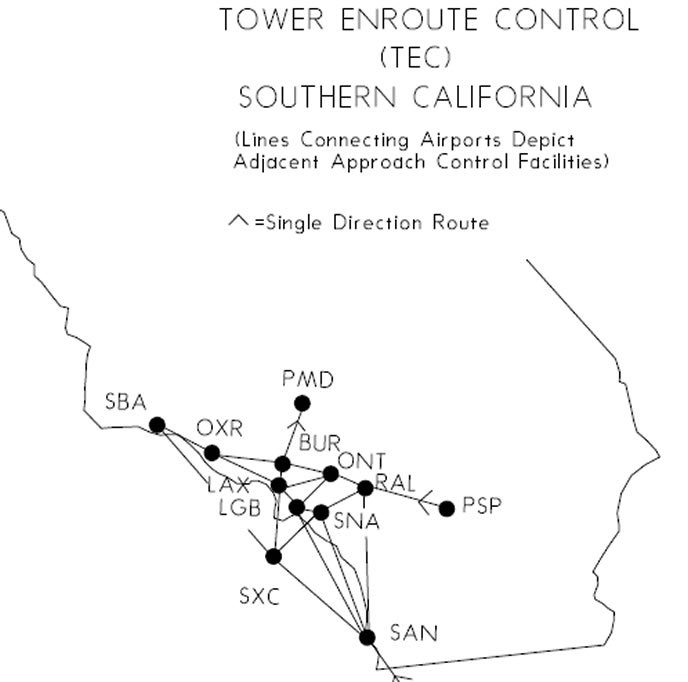

As the map shows, TEC routes are heavily concentrated along the Pacific coast from Tijuana to Palmdale and Palm Springs to the east. To no one’s surprise, the center of gravity is about in the middle around KLAX. Some routes are unidirectional as indicated by the arrows.

The SoCal TEC list format is quite different from that found in the Northeast. The From-To format in the first column is quite clear in that if you depart any of the San Diego airports, you can get to KHHR via the SANN7 (or SANN8) route(s) that can even specify an approach: OCN V23 SLI SLI340R WELLZ HHR RY25 LOC. Northeastern TECs are nameless and do not include approaches.

As for altitudes, you’ll see letters preceding the altitude in thousands. J means jet; M denotes turboprops or special aircraft that cruise at or above 190 knots; P is for non-jets with the same cruise speed and Q is for most of us: non-jets with cruise speeds of 189 knots or less. These equipment codes and definitions are completely different from those used in the Northeast.

When filing, you can enter just the coded route identifier as your route. Be sure you file the route allowed for your type of aircraft. This is important because there may be more than one route to your destination, distinguished by aircraft type. Expect the coded route identifier to be your ATC clearance instead of getting the full-route description. Enter the altitude that corresponds to your aircraft type. Towers are required to advise departing aircraft to expect the altitude indicated in the TEC five minutes after departure unless otherwise specified.

It’s important to get the altitude right. The altitude associated with each TEC route is selected in order to assure IFR separation for arrival and departure routes as well as overflights to, from and over all airports in the Southern California area.

Accommodating Airport Ops

Los Angeles International Airport (KLAX) and four other airports (KONT, KSAN, KTOA and KSNA) have two options due to winds that affect the traffic flows and runways in use. It may be necessary for you to know which set of airport operations are in use, meaning which way the wind is blowing, at these airports if you read a route containing the notation, say, LAXE or SANE.

To indicate the operation in effect, a direction (N, S, E, W) is added after the airport identifier:

W is for west indicating normal conditions, denoted as (LAXW). E is for east, such as (SANE) and N for north such as (SNAN), both indicating other than normal operation. If no letter follows the airport, you can use that route regardless of which way the wind is blowing and which runways are in use.

Other destinations to which you might fly could have different arrivals due to LAX landing east; they have the notation (LAXE). Torrance Airport is also unique because the airport is shared between Los Angeles and the Coast area of Southern California TRACON; for Runway 11 departures use Coast area routings and for Runway 29 departures use Los Angeles area routings.

Delay Notifications Under TEC

When tower enroute control service is being provided, the approach control facility whose area contains the destination airport is required to issue total delay information as soon as possible once the aircraft enters its approach control area. Whenever possible, the delay information must be issued by the first terminal controller to communicate with the aircraft.

Unless a pilot requests delay information, the delay notification can be omitted when total delay information is available to pilots via ATIS.

Final Thoughts

It’s puzzling as to why the FAA implemented TECs in only two areas of the country and did so quite differently. The 30+ Class B mega-airports are surrounded by multiple reliever airports that would make ideal TEC satellites. Perhaps it’s that there must be sufficient overlapping Approach Controls in order to make TEC feasible for up to two-hour flights. We might never know.

Fred Simonds is an active CFII in Florida. See his web page at www.fredonflying.com. He was sad when he found no TEC routes close to home.