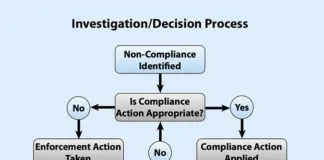

Before I was an air traffic controller, I dabbled with computer programming. Both fields involve complex problems that are often broken down to simple if/then statements: if condition A is true, you do X. If condition A is false, you do Y. Thousands of these tiny statements may be the bricks of a massive application or website’s structure.

Each flight is also a complex collection of factors, including the winds, traffic, and weather you’ll encounter, all impacting yours and ATC’s decisions going forward. The black-and-white rules of ATC allow controllers to navigate these fluid situations through a series of simple, often yes-or-no questions.

Let’s review how that conditional approach is especially apparent when ATC is handling the visual side of operations, including visual approaches and visual separation.

Laying It Out

FAA Order 7110.65—the ATC manual—in section 7−4−2, Vectors for Visual Approach, says: “A vector for a visual approach may be initiated if the reported ceiling at the airport of intended landing is at least 500 feet above the MVA/MIA and the visibility is 3 miles or greater.” Is the airport reporting a ceiling less than 500 feet above the minimum vectoring altitude? We must vector you for an instrument approach instead of the visual.

Now, if you happen to catch sight of the airport while being vectored for that instrument approach—and the field is VFR of course—we can still clear you for a visual approach. That happens all the time. Imagine the ceiling is 1800 feet and the MVA is 1500 feet. That’s only 300 feet above the MVA. I must vector you for the ILS. However, if on that vector I descend you to the ILS’s FAF altitude of 1500 and you spot the airport as you pop below the 1800 foot overcast, I can clear you for the visual.

What about airports without weather reporting, such as many non-towered airports? It says, “There must be reasonable assurance (e.g. area weather reports, PIREPs, etc.) that descent and flight to the airport can be made visually, and the pilot must be informed that weather information is not available.” In fact, an attached note passes the responsibility to the pilots: “At airports where weather information is not available, a pilot request for a visual approach indicates that descent and flight to the airport can be made visually and clear of clouds.”

To clear an aircraft for a visual approach, per 7110.65 7-4-3 the pilot must report, “The airport or the runway in sight at airports with operating control towers,” or “The airport in sight at airports without a control tower.” The aircraft must also meet one of the following criteria: 1) Be number one in the sequence. 2) Report a preceding aircraft in sight and be instructed to follow it. 3) If they’re following someone but can’t spot them, must ensure that radar separation is maintained between them until visual separation is achieved.

The requirements aren’t that complex or numerous, but they are clear: the pilot must get the airport, runway, or preceding airplane in sight. What happens when weather leaves things a bit… hazy?

A Definite Maybe

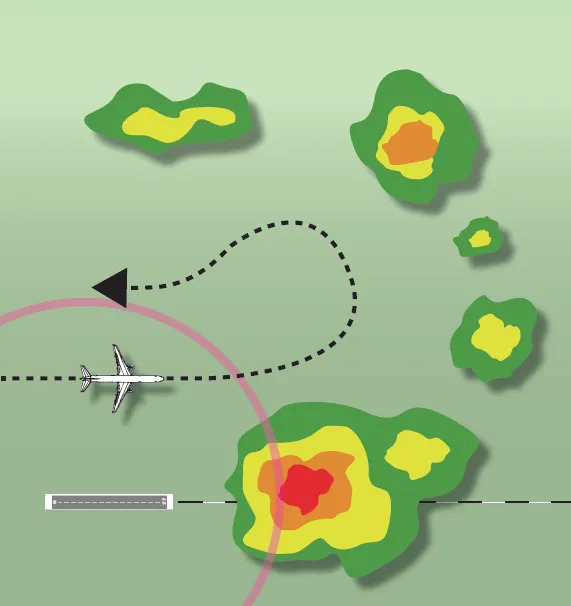

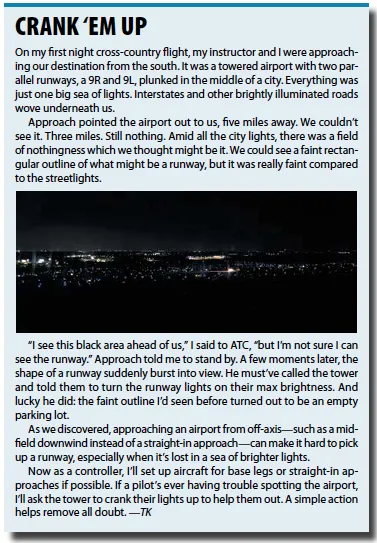

I was vectoring an Airbus for a visual approach into our airport. The airport ceiling was well above the MVA, but there was a thunderstorm blowing up on the final, starting at about a six-mile final, extending outbound from there.

I’d already described the weather to the A320’s crew and told them my plan was to run them in on a tight right base for Runway 27. I vectored them on the right downwind, then aimed them at a five-mile final, descending to 1500 feet. In the turn, I called the airport, “Two o’clock, seven miles.”

A moment passed. “Uh…” The pilot paused, then said, “I think we have it in sight.” The confidence in his voice was, shall we say, lacking.

While life is full of gray areas, there’s no room for them here. As a floppy-eared green Jedi once said, “Do or do not. There is no try.” This is a binary situation. You either have the field in sight or you don’t. An “I think…” doesn’t meet ATC’s requirements.

I’m aware there are many factors working against the crew—convective weather, a tight base, and perhaps lack of familiarity with the airport surroundings. Clearly, this is not an ideal situation. However, I still needed a definite yay or nay. I gently said, “Verify you have the airport in sight? Airport now two o’clock six miles.”

A pause, then the pilot said, “Oh, we’ve got it in sight now.” Excellent. A little nudge, and the requirements were met. I cleared them for the visual approach and switched them to tower.

Know Your Limits

What if he didn’t get it in sight? It’s critical to have a Plan B. This would play out with the next aircraft: a Boeing 757.

The 757 was about 30 miles behind the A320. I told him about the thunderstorm and explained what I’d done with the previous arrival. He was willing to give it a shot, so I gave him a similar vector for the right downwind.

However, by the time the 757 was abeam the airport on the right downwind, the weather was worse. The heavy precipitation had encroached on a four-mile final. A lighter aircraft might have been able to sneak in, but not the big ol’ Boeing.

It wasn’t looking good from where I was sitting, but the final say was with the flight crew. What ATC’s radar shows can differ from the picture out the window. I told them, “Heavy precipitation now extending to a four-mile final. Say intentions?”

While all this was going on, areas of moderate and heavy precipitation had been flaring up to the north and east of the 757, about 10 miles away, and there was the storm southeast of him. He was essentially boxed in from three sides. If he couldn’t get in on the visual, the only way out was the way he had come.

“It’s not going to work,” he said definitively, “Not enough room for us.” I already had my alternative plan ready to go. “No problem,” I said. “Climb and maintain 5000 and turn left—left turn all the way around—heading 270.” This would rack him around in the box made by the precipitation and exit him safely out to the west.

While the storm had created a questionable situation, the crew was decisive and knew their limits, and I had an “out” on deck. I told him to expect holding west of the airport. About 15 minutes later, after a few turns in a hold, the storm shifted the airport’s winds enough that that he was able to land on Runway 9.

If I Can, I Will

With the 757, there was nothing that could save that initial attempt. However, if there’s a viable option that can improve chances of success, we’re all ears. The emphasis is on viable.

I was vectoring a Citation for a visual approach to a satellite airport. Scattered clouds were reported at 2500. I descended him to 2000 and advised him of the airport position.

Here’s where I mention that there are limits to what a radar controller can “see.” Our radars don’t depict cloud coverage, only precipitation and particulates. Rain? Snow? Hail? Thick smoke? Those appear on our scope. Clouds and fog do not. All we have on hand are METAR/SPECI weather observations and pilot reports.

Now, I received one of the latter: “We’re right in a layer. Can we get lower?” My minimum vectoring altitude there was 1500 feet there, so I descended him to that. Again, I called the airport. “Uh,” he said, “we’re kind of in-and-out of the bottoms. Any lower?”

Like the 757 crew knowing their limits, I had to know mine. He was already at the MVA. One thing controllers are taught in training: a pilot might try to talk them into allowing a situation that puts the unwitting pilot himself in danger. Sure, if he was in the bottoms, all he’d need was a couple hundred feet lower. Unfortunately, that was a couple hundred feet I didn’t have.

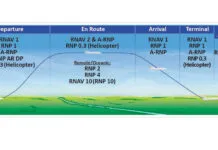

“Unable,” I replied. “You’re already at my minimum vectoring altitude. Expect vectors for the RNAV approach.” He landed via that approach. His pilot reports of course demonstrated that the ceiling was not 500 feet above the MVA. All subsequent arrivals received RNAV approaches.

Forget the Fish Finder

Forget the Fish Finder

Visual separation is another area where there’s no room for vagaries. ATC must typically maintain at least three miles laterally or 1000 feet vertical of radar separation between IFR aircraft. However, if one aircraft can get another aircraft in sight, we can get them to separate or follow each other visually instead and forgo those radar separation minimums.

Per 7110.65 7-2-1, ATC can enact pilot-applied visual separation when, “The pilot sees another aircraft and is instructed to maintain visual separation from the aircraft as follows: (1) Tell the pilot about the other aircraft. Include position, direction, type, and, unless it is obvious, the other aircraft’s intention. (2) Obtain acknowledgment from the pilot that the other aircraft is in sight. (3) Instruct the pilot to maintain visual separation from that aircraft.”

This is useful when we want to get airplanes to follow each other on a visual approach sequence. Section 7-4-3 of the 7110.65 says an aircraft can be cleared for a visual approach if “it is to follow a preceding aircraft and the pilot reports the preceding aircraft in sight and is instructed to follow it to the same runway.”

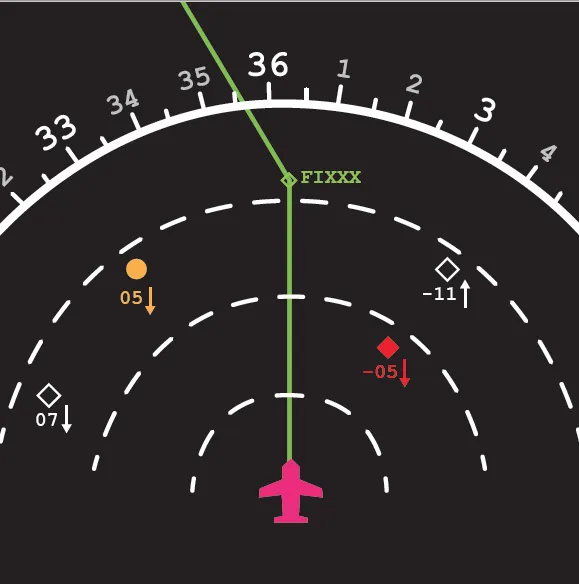

Note the words “in sight.” Modern aircraft often have traffic information displays showing the position of aircraft in their vicinity. I’ll often call traffic to an aircraft, and they’ll have the guy in sight already because they already spotted him coming on their own display. Those systems absolutely provide excellent situational awareness and can get the pilot scanning in the right place. However, for ATC’s purposes, we need pilots to see the traffic out the window with their eyes.

The other day, I was vectoring a King Air to follow a Boeing 737 for a visual approach. I called the traffic to the King Air, “Eleven o’clock, five miles, 737, descending out of 2000.” The King Air replied, “We’ve got him on the box.” Okay, that’s great… but it doesn’t help me out at all per my requirements.

Again: I need eyeballs on the actual airplane, not on a target on a screen. An appropriate response would’ve been, “Searching for traffic.” I called the traffic again. The pilot came back, “I think we’ve got him crossing over the interstate.” Here we have another “I think…” situation.

As with ATC’s standards for reporting an airport in sight, the pilot either has the traffic in sight or doesn’t. Until the pilot is 100% certain, we cannot act on the information. So, I called the traffic again, throwing in a bit of detail. “Traffic to follow, 10 o’clock, four miles, 737 descending out of 1700. Delta Airlines colors. Verify traffic in sight.”

“Oh, yeah, we got him in sight now.” That was the definitive response I needed. I responded, “Follow that traffic. Caution wake turbulence. Cleared visual approach….”

Clearances like these must be built on a solid foundation. Just like you can’t build a castle on quicksand, you can’t build a clearance on uncertainty.

Tarrance Kramer appreciates black-and-white answers while working traffic in the Midwest.