These pages often contain encouragement to pilots not to become so completely reliant on GPS that its loss constitutes no less than an emergency. GPS, both panel-mount and portable, can fail for external and internal reasons. Read about these GPS-failure events culled from ASRS reports. We hope this article will lead you to get some practice using terrestrial nav.

Jammed Up

An ATP ferry pilot was repositioning a series of aircraft between Flying Cloud and South St. Paul Municipal airports near Minneapolis. He experienced momentary—but total—GPS outages on every flight over one area.

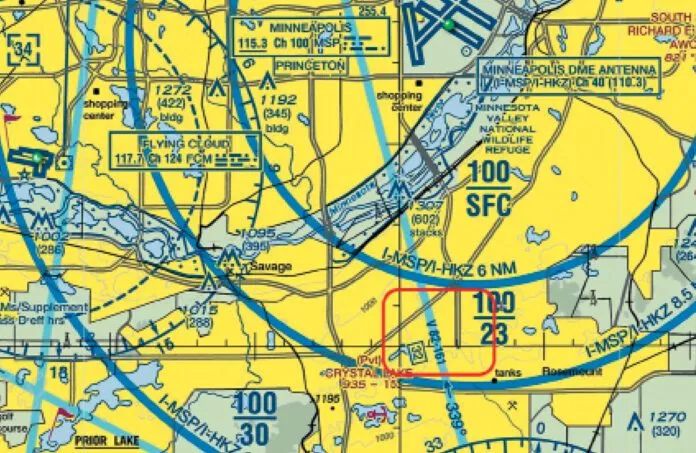

Circumnavigating south of MSP’s Class B airspace below the Class B shelf at 2000 feet, the outages occurred in the area depicted in red, below. All units affected were Garmin GTN 730s but one, a GNS 530. This unit didn’t lose signal but showed an error message briefly.

There might have been an illegal jammer in the area. It would be wise to ask ATC if anyone else was having trouble and report the outage. Submit a report at www.faa.gov/air_traffic/nas/gps_reports.

Intentional Jamming

Reaching about 1000 feet on its initial climb from Albuquerque airport, the Cessna Skylane’s GTN fell into dead reckoning mode, making terrain awareness unavailable. When the pilot checked in with ABQ Center, they replied there was active GPS jamming at White Sands Missile Range within R-5107B.

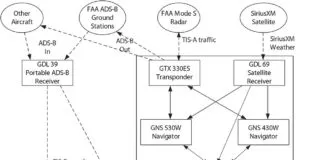

Advising that he couldn’t maintain terrain clearance, ATC issued him an IFR flight plan. His portable Garmin 695 had about half its usual signal, but he could navigate. Unfamiliar with the area and perhaps with different avionics, he said he could have had a controlled flight into terrain accident.

A pilot was en route in the Jacksonville, FL area at 2000 feet when his GPS, iPad, and EFIS said RNAV and ADS-B signals were lost. JAX Approach Control said they did not know of any GPS outages, and no one else was having trouble.

After landing and about 20 minutes later, the system returned to normal. Another pilot had the same experience. He called Approach Control again. By then, ATC had received several reports but had no prior notice from the Navy, which has a significant presence in Jacksonville.

There were no local NOTAMs, but the pilot found a NOTAM for an outage lasting for about a week at various times at JAX Center.

Our persistent pilot recommended sending the NOTAM to all Approach Control facilities underlying the testing, local airports, and service providers such as ForeFlight to advise them of a possible outage. This is already often the case.

He added that if the outage had occurred in IMC, it would have considerably spiked pilot workload. With testing on the increase, this is another thing to know before we go.

Airspace

Many ASRS reports are CYAs resulting from momentary GPS failures near Class B, C, or D airspace where the reporter might have been trying to avoid a violation. Here are two examples.

En route northbound past the Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, (KMYR) Class C airspace, VFR at 3000 feet, the pilot deviated northwest toward Conway (KHYW) airport to avoid KMYR’s airspace. Good move. Nearing KMYR, his GPS encountered interference, and the ADS-B ownship indicator froze on his moving map.

When the GPS recovered, it showed him “near or touching” the outer edge of the Class C. He made a 180-degree turn, then turned north to skirt the airspace as planned. His GPS didn’t issue an airspace warning.

He later determined the ADS-B failure was due to shadowing, which occurs in single-antenna installations when the aircraft’s fuselage blocks transmissions from other aircraft.

Similarly, a Navajo pilot’s GPS fell into dead-reckoning mode but initially went unnoticed. Recovering about five minutes later, it showed him close to Class B. Pilots often overlook such messages.

A GA aircraft operating near Philadelphia (KPHL) at 3000 feet was on a VFR fight to Wings Field, which lies north of KPHL and beneath the outermost shelf of Class Bravo beginning at 3500 feet. ATC instructed him to climb to 3500 to avoid a TFR. Southwest of KPHL near Wilmington, Delaware, a lost GPS signal distracted him from confirming his clearance through the Bravo. He soon realized he was inside it without confirmation. ATC said nothing, but he reported it anyway. That was wise because months can pass before FSDO might call.

In-Flight Troubleshooting

Troubleshooting GPS signal problems while airborne is useless unless you have access to the antenna cable. If it’s panel-mounted, check the system status page to see if it’s receiving satellite signals. If not, there could be an antenna or interference problem.

A Piper Cherokee departed VFR but planned to fly around a Class D airspace en route. At some point, the GPS lost signal, and the airplane symbol stopped moving. The pilot realized the map was not updating after he entered Delta airspace and soon found a loose antenna wire. He now plans to fly with a backup GPS, use flight following, or file IFR.

Another VFR pilot realized his map was not updating and resorted to using his iPhone backup. To his dismay, he was inside the outer shelf of Class Bravo airspace. He exited quickly and landed. Behind the panel, he discovered the GPS antenna cable had vibrated loose and fallen off.

This pilot blamed himself for relying on the GPS too much and not “good old pilotage” using landmarks. He noted his GPS had no alert to warn of signal loss. He also knew a light wind was blowing him toward Class B. In the future, he plans to keep his cell phone handy whenever he ventures near Bravo airspace.

Unseated

Nearing his destination, the pilot encountered mystifying radio and GPS problems with his GNS 430W. Failing three times to activate runway lights, he contacted Tucson Approach. His GPS was also intermittent.

With an estimated range of about five miles, he lost and regained contact with Approach several times but heard and set a transponder code. He elected to land in Tulsa, Oklahoma, because of its after-hours services. Cleared to land, Approach told him to expect light gun signals from the tower, which described his transmissions as broken and scratchy. Near the airport, he heard the tower well and landed.

The next day, an avionics technician noticed the 430W was not fully seated and quickly solved the problem.

Our pilot said the airplane was new to him, and hadn’t noticed an issue earlier. He now visually inspects the GNS 430W, audio panel, and transponder during his preflight inspection to ensure they’re correctly seated and functioning.

He assumed they were installed correctly by the previous aircraft owner. “I trust maintenance shops to do work and repairs correctly, but it’s now ‘trust but verify’ as I’m responsible.”

Takeaways

Check GPS NOTAMs, and RAIM if appropriate, before departure, especially for jamming.

Be aware of frozen ownship symbols, LOI, and DR warning messages. Many VFR pilots came close to or entered airspace because they weren’t paying enough attention. Turn generously away from nearby airspace.

There’s little in-panel GPS troubleshooting except checking the status page. Loose cables are the most common cause of trouble in handheld units. Your cell phone or EFB aren’t good backup, but are better than nothing.

Ask ATC for help. They want to prevent a violation as much as you do.

If you entered airspace briefly and exited promptly, and there was no safety of flight issue, ATC seems inclined to let such incidents pass. If they must turn an airplane or if there is a separation issue, that’s another matter. File an ASRS report within ten days. The FAA is fussy about that.

Fred Simonds files an ASRS report before every flight. That way, he thinks he’s covered (not).