Flying an airplane involves multiple concepts from physics: Bernoulli’s principle, centrifugal force, Newton’s law of gravity, to name a few. There’s one more natural law, though, that isn’t in the science textbooks: the faster you’re trying to get somewhere, the more likely you’re going to get unexpectedly delayed.

Today’s a perfect example of that. You and your family are running late flying IFR south-southwest into California to catch a cruise. Sacramento (SAC) is off your nose to the left. The plan? Fly into South County Airport (E16) near your sister’s house, pile both your families into a minivan for a drive to the port, and enjoy twelve days of seaborne relaxation. Unfortunately, weather and last-minute packing delayed your departure. Your trusty Cessna 182 Skylane only has enough raw speed to make up a fraction of that time.

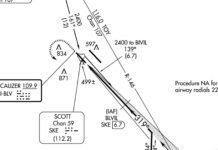

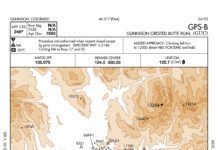

Now, air traffic control’s given you even more bad news: they’ve got to reroute you around the Class B and Class C surrounding San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose airports, and hook you back into E16 from the south. The route? SAC, Manteca VOR (ECA), Panoche VOR (PXN), Salinas VOR (SNS), and—finally—E16. Total added time according to the GPS? Thirty-eight minutes.

That’s cutting things dangerously close to your ship’s departure time. If you miss that cruise, the least of your worries will be a few minutes of gas money. We’re talking thousands of dollars of nonrefundable cruise tickets, the profound disappointment of the kids in your backseat, and your spouse saying something about the airlines being a better choice.

Don’t lose hope. When there’s a messy reroute in your future, you may be able to get out of it if you’re willing to play it really smart, get just a little dirty, and learn to bend the ATC system to your needs.

Playing in the Street

Why is this reroute even required? Wouldn’t it be better for ATC just to take you direct and get you out of their hair more quickly? No, it isn’t.

Remember the 1980’s vintage arcade game Frogger? You controlled the eponymous amphibian trying to cross a busy highway, dodging cars and trucks. One wrong move and your little friend was road kill. To controllers, that’s what it’s like threading your IFR Skylane through the flow of IFR heavy metal in and out of Class B airspace complexes. To avoid playing dodge-the-Cessna, the reroute is issued to keep you well out of the way.

The fixes, navaids, and airways controllers use for these reroutes aren’t just conjured up willy-nilly. Letters of agreement between ATC facilities typically lay them all out in black and white. Each facility’s controllers are required to comply with them.

While reroutes certainly reduce variables in the safety equation, we controllers recognize the headaches they cause. Believe me, issuing these things is nothing personal. There’s not a whole lot we can do about it from our end. We’re required to inconvenience a minority to preserve the system’s overall safety and organization.

Regardless of the reason, this particular routing is just horrible. Weaseling your way out of it will require an understanding that ATC is a service-oriented system, use of good judgment, and possibly a little bit of a compromise on your end. The goal? In the interest of saving your vacation, you’re going to need to pull off not one, but two bait and switch deceptions.

Shortcuts and Skullduggery

Looking at your chart, this reroute takes you around San Francisco’s Class B and Oakland and San Jose’s Class C airspace so you’re not descending through their traffic. Well, what if you asked ATC to change your destination to San Jose itself?

Wait… don’t you need still need to get to South County? Of course. The idea is this: if you ask to go to KSJC, you’ll be vectored directly inside the airspace the reroute was circumnavigating. Then—when the time is right—ask to be cleared back to E16. Bait. Switch. Times two.

Perhaps now you’re asking, “Can’t ATC just ‘unable’ a destination change?” Not really. As a controller, I can’t make you land somewhere you don’t want to land. I may not be thrilled about the additional workload your double destination change might cause me, but I also can’t just arbitrarily say “unable.” Yes, you might get delayed with vectors around other traffic or airspace, but that’s about it. Even if your destination is NOTAMed closed or under a TFR, we can’t make you go elsewhere if you’re perfectly happy carving circles in the sky and waiting it out.

Is it a big momentous deal to ask for a destination change? Not usually. Some pilots may conjure up a phony story. “Uh, the boss in the back needs to stop off at KSJC instead and check out one of her franchises.” Don’t get silly and shoot for an Academy Award acting nod. The truth? Unless it’s an emergency, most controllers couldn’t care less about the “why.” They just need to know the “what and where” as soon as you can dish it out. Just keep it clean and direct. “Approach, Skylane Seven Eight Bravo, we need to change our destination to San Jose.”

The controller may not be all smiles, but you’ll likely get your clearance directly to KSJC. “Skylane Seven Eight Bravo, cleared to San Jose airport via radar vectors. Descend and maintain 4000, fly heading two zero zero.” San Jose here you come. Goodbye to that marathon detour around it.

Timing is Everything

San Jose’s 20 miles ahead now as you descend through 5000 feet. ATC’s dutifully vectoring you for the ILS approach, none the wiser that you intend to pull another fast one. E16’s fifteen miles south of KSJC. At what point do you advise ATC that you’d actually like to change back to your original destination and complete the second bait and switch? Heck, if you do it too soon, you might get stuck with that original reroute.

You certainly don’t want to wait until ATC has already vectored you on to the fake destination’s ILS and told you to switch to tower. If you did that to me, I’d be livid. You wasted my time and the fuel of any other traffic I had to vector or slow down to put behind you. Not only that, but you’re also down low and in the mix with my other final traffic, so my vectoring options are limited. Not cool.

Instead, use good judgment and find a happy medium. Every airport is so different it’s hard to establish one set of rules for all. However, based on my experience, I would wait until you’re no closer than fifteen miles and about level with the upper limit of the “fake” destination’s airspace. That’s 4000 feet for the inner circle of KSJC’s Class C. That would keep you above the traffic on final and the departures on their initial climb, allowing ATC to vector you as needed.

In that position, you’re so close that ATC likely won’t gig you with that massive reroute, but they’ve also got a bit of breathing room. That’s a good thing in your favor. You’re basically saying, “You’re stuck with me, but you can still work with me.”

Once you’re within fighting distance, pull your final bait and switch. “Approach, Skylane Seven Eight Bravo, we’d like to change our destination back to South County.” A “sorry about that” from you could help ease ATC’s frustration, especially if you’re talking to the same controller who issued you your first destination change clearance.

Like pilots, we’re trained to make rapid decisions, so perceived indecisiveness—especially about something as basic as where you’re landing—doesn’t leave a good taste in our mouths. Chances are, though, the controller’s also seen this kind of maneuver before. After working traffic for a while, sharp controllers tend to pick up on the shenanigans pilots pull. They know when they’re being played.

Nonetheless, it’s ATC’s job to provide the service. “Skylane Seven Eight Bravo, cleared to South County airport, fly heading one niner zero, maintain 4000.”

Easing the Tension

Earlier, I mentioned a compromise on your end. What could make life easier for ATC? Cancelling IFR and proceeding onward with VFR flight following. That dispenses with ATC’s requirement to separate you from other IFR traffic by 1000 feet or three miles. They’re still watching over you, but it opens a lot more vectoring options and greatly improves your chances of flying direct to your destination.

Here again, good judgment applies. Only do this if the weather between your current position and your destination supports this action. If you’re in the soup, don’t endanger yourself over a few extra flying miles. The second ATC hears you say, “Approach, if it helps you out, I can cancel IFR,” you’ll likely get an instant, “IFR cancellation received. Maintain VFR.” Be ready for that.

What if your present position is absolutely clear and a million VMC, but your destination is reporting IMC with that legendary coastal fog creeping over the mountains? You could cancel IFR, fly the majority of the distance, and then request a popup IFR clearance and an instrument approach once you’re really close to your real destination.

In this case, the weather’s excellent from here to E16. “Approach, I’d also like to cancel IFR, but keep flight following to South County.” ATC replies, “Seven Eight Bravo, IFR cancellation received. Maintain VFR at or above four thousand. Proceed on course to South County.”

Eyes scanning outside the windshield, you think about the next time you fly in the area. Maybe you’ll file directly to San Jose and rely only on a single bait and switch to E16. Hopefully any future trips won’t be so pressed for time.

Any good cheater knows he can only push things so far before he gets caught. For that reason, don’t bet on the outcome always going your way. If the weather’s crap, you may have to remain IFR. Perhaps you’ll get vectored like mad to steer clear of other traffic. In highly complex, restricted airspace, like that around the New York or Washington D.C. complexes, you’re probably going to have to suck up whatever reroute they give you.

Fortunately for you, today is not that day. As you descend VFR into South County, the Pacific Ocean glistens off your right wing as you dip below the coastal mountains. Soon you’ll be out there, enjoying the cruise with your family. Despite the stressful morning, you can already feel the relaxation easing into your bones. With the way your luck’s turned out, maybe a little time in the ship’s casino will help pay for your vacation.

Tarrance Kramer is a controller in the southeastern U.S. He’s wise to the destination-change trick, but still tries to work with his victims as much as other traffic permits.

ATC has a system of priority. Aircraft that are both identified and cleared on IFR flight plans rank at the top. Unidentified VFR targets live on the bottom rung. What if you want to climb that ladder, but the controller you’re talking to is too swamped to help you up?

Imagine you depart a non-towered airport VFR under a 1500 foot overcast. Your filed IFR flight plan route takes you eastbound with a requested altitude of 7000. You dial in the airport’s approach frequency. Voices burst into your headset. The controller doesn’t stop talking for five minutes. Each time you try him, he tells you to standby, stranding you under the deck. You need your IFR clearance to climb, but right now you’re just another unidentified VFR target. What to do?

Figure out the next frequency on your route. Is it attached to the same approach control facility? Yes? You might be in luck. If you’ve never visited an ATC facility—something I recommend every pilot do—one thing you’ll notice is the control positions are typically situated side by side in the same room. The controller working the subsequent frequency is likely sitting right next to the busy guy and is well aware his coworker is swamped. His radar scope also displays targets in adjacent airspace.

Dial in that second frequency and—if that controller’s not busy as well—tell him your location, your IFR clearance request, and that you’ve been trying to raise the other controller. He may make you ident to verify your position, determine how far you are from his airspace, and identify any traffic conflicts. If things look good, he may step over to the busy controller’s sector, literally tap your target on his scope with a finger, and say, “Point out. IFR going up to 7000 with your approval.”

If the other controller says “approved” that grants controller number two permission to take responsibility for your airplane in the other guy’s airspace—a “point out” in ATC terminology. The controller you’re talking to issues your IFR clearance, says “radar contact” when you tag on his scope, and climbs you above the overcast. You get what you need. Controller number one gets some workload relief. Score one for ATC teamwork.

Of course, keep in mind, there are never any guarantees. What if controller number one said “unable” to the point out? What if you’re too far from the second controller’s airspace for his comfort? Also, the chances of success vary between approach controls and centers. Dealing with approach? You could have only 10 or 20 flying miles before you hit the second guy’s sector. With a center, it could be 50 or 100 miles or more, and that’s a long way if you’re a slow mover. —TK