We’re a good 10 years into the brave, new world of technologically advanced aircraft (TAAs) and yet their glorious promise is only half-fulfilled. It makes you wonder how long after NextGen is officially “here” that we’ll feel it was worth the mandatory accessorizing of our aircraft.

Looking at what we’ve got in our hands today, I’ll grant that at least three items—lightning detection, datalink weather and GPS approaches—have made real changes in mission capability. That is, there are flights you can complete with these items that you wouldn’t have attempted (because you’d be threading thunderstorms blind) or couldn’t have executed (because there was no approach available).

All those other goodies—moving maps, advanced autopilots, synthetic vision and so on—are fun but it’s a hard sell to say they add to mission capability. You may be more comfortable flying an ILS approach with your little aircraft straddling the magenta line on the moving map, but keeping the needles centered gets you to the same minimums with or without the pretty picture. That said, sometimes the cumulative usefulness of the gadgets does legitimately turn a “no-go” into a “go.”

Here are two real-world flights where the on-board gear made a difference. In case one, it allowed a flight to complete where it would have been aborted. In case two, it turned a possible no-go into a go with options.

Thread the Needle

The mission was a 400-mile flight from Portland, Maine, to Chautauqua, N.Y., and the aircraft was a well-equipped Columbia 400 (dual GPS, stormscope, glass cockpit … you get the idea). The roadblock was a line of early-morning thunderstorms moving through central N.Y. Because the storms were mostly to the south of our route, the plan was to head out in good weather ahead of the storm and look for a spot to cross or divert north and hook around the top of the line. We launched fat on fuel and ready to negotiate as we went.

We were just crossing the border between Maine and New Hampshire when the datalink weather on the MFD showed the southern storms had gotten serious. There was a good helping of lightning and a blue box that said, “CSIG.” That’s short for “Convective SIGMET,” in case you were wondering. We were already angling north toward Utica, N.Y., and it looked like diversions further north would be needed.

There was a still a wide area on the NEXRAD with only green and isolated yellow returns near our current route. The plan was revised to head for that area and work our way through, staying visual with the storms as long as possible. As we trundled along, we heard airliners diverting from destinations to the south. Boston Center was starting to sound harried with the juggling act being thrust upon them. Our plan B was turning back and becoming part of this building mayhem—not real attractive.

By the time we got over New York state and close to the line, we had turned another 15 degrees north and our target gap had narrowed, but it was still doable. We had been visual up to this point and could see that we’d be punching through in IMC, but we’d be well away from the serious cloud towers. All we needed was another 10 miles northwest before we turned southwest and crossed the line. Then Center threw a huge wrench in the works: “Columbia Two Three X-ray, I can only let you keep going another couple miles and then I’ve gotta turn you south.”

What? You can’t turn us back now. Just 10 more miles and we’re home free. And definitely not south, as that would put us right into the maw of the storm. We told the controler this in a more polite manner, but with a clear “unable” for any vector southward. He said he had no choice. It was south or about face. Our call.

There’s a negotiation technique where you try and separate real conflicts from apparent ones. We wanted further north; he wanted no further north. Real conflict, right? Actually, no. It evaporated when we asked why he couldn’t give us 10 more miles.

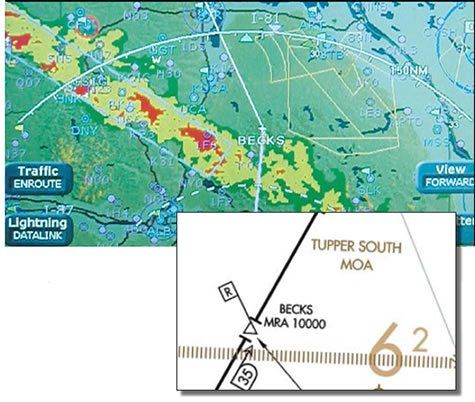

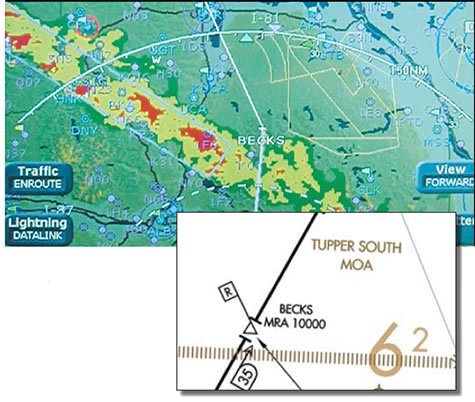

It turned out the Tupper South MOA was hot and we were getting too close to it. Here was the leverage point, because there didn’t have to be a conflict: We wanted more north and he needed us to stay out of the MOA. We pitched a plan: “Boston Center, Columbia Two There X-ray, we have the MOA painted on our moving map. Let us maneuver ourselves around this weather and we can guarantee that we will stay clear of the MOA. We may get right next to it, but we won’t enter it.”

That’s a pretty big request because, even though we’re saying we’ll stay clear, it’s the controller’s ticket on the line as well as ours if we blow it. But if we do make it through, that’s one less aircraft he has to juggle on a reroute. He came back after a pause: “Columbia Two Three X-ray, approved as requested, but you absolutely must stay out of the MOA.” It might have been my imagination, but he sounded nervous.

However, we now had immense freedom. Instead of sticking to a route, we followed whatever heading we needed to wiggle through without entering the red blobs to the left of the little airplane icon or the yellow line on the right. Twenty minutes later we were in the clear and told Center we could take direct Chautauqua. We got the direct and—this part came as a surprise—we got a deeply sincere thank you. Twice.

In retrospect, it shouldn’t have been surprising. We used our resources to do something the controller couldn’t have done and solved everyone’s problems.

Assessing the Options

Case study number two involves a G1000-equipped Cessna 172. The departure point was again Portland, Maine, with a destination of Rangeley, Maine. Rangeley is only 80 miles away and tucked into a small bowl amidst 2000-foot hills. This was November in the north country so the 2500-foot overcast at Portland put ice into the equation if we needed to go IFR.

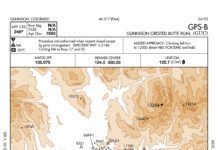

Doing some basic flight planning to assess the options for staying below the clouds, it seemed we needed 3000 feet to the cloud bases to get through, but only for the last 10 miles of the flight. The bases up by Rangeley were at 3000, so running VFR below and heading for a valley just southwest of the airport to get into the bowl could work. I noted down the lat/long for the right valley so I could enter it as a waypoint in the GPS and ensure I didn’t fly up a dead-end. When I leveled off leaving Portland, I’d be able to see up towards Rangeley and guess at the slope of the clouds. The terrain display on the G1000 would help determine whether my altitude had enough clearance for VFR below. I filed that scheme in my mind as Plan A.

Now if the clouds didn’t slope and VFR below was out, Plan B would have to include IFR. A look at the ADDS flight plan tool showed a 25- to 50-percent chance of trace or light ice at 3000 and 4000 feet, but no chance of ice at 5000 or higher. That looked a lot like clear above. A check of the Skew-T diagrams online confirmed this. Tops looked to be between 4000 and 5000. The launch was early in the morning so no PIREPS were available.

This meant Plan B would be climbing to on-top and hoping for a VFR descent into Rangeley. The clouds often broke up in the mountains, so this was possible. The climb would also be a good test to see if I did pick up ice from a short exposure and I could do the test over friendly terrain with high bases. If I did pick up ice on a short climb, then shooting an approach through the same clouds in the mountains was right out. If I didn’t, then Plan C was an option.

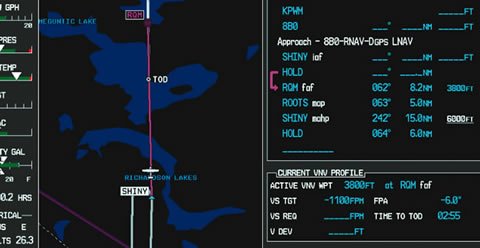

Plan C was to go VFR on top until it was time for the approach and then fly it so as to minimize my exposure to potential ice. Flying the plate as published would have meant a 10-mile stint at 3800—right in the heart of the cloud deck. Instead, the plan was to use the vertical navigation on the G1000 to descend at a steep angle and high rate from the initial altitude of 6000 right to the MDA of 2380 without leveling off in-between. With VNAV, I could do this to pass through the stepdown at RQM or to hit MDA any distance before the MAP I wanted.

The approach is non-radar, so I wouldn’t know if B or C was the ticket until I got there, I’d plan for VFR-on-top direct to SHINY and a cruise clearance. That would give me all the flexibility to shoot the approach however I needed.

Plan D wasn’t a plan, so much as an awareness. I felt pretty confident that even on the approach, icing wasn’t a factor. But on the off-chance I found myself at MDA, still in the soup, picking up rime and now unable to climb back up on the missed, I noted a lake under the missed approach course. In an emergency, that was my out: Circle down even further over the water. I knew the lake would be painted on the GPS so long as I left terrain turned off on the MFD map.

Just for clarity, here’s a sum-up of the high-tech integration: User waypoint on the GPS to ensure flying up the correct valley if ceilings are low, terrain map to assess the viability of VFR-below, GPS approach for best accuracy if needed at Rangeley, VNAV for continuous descent to minimize icing exposure and GPS map of lake in worst-case scenario.

What actually happened? We launched from Portland and leveled off just below the clouds at a mere 2000 feet. The tops of the hills in the distance were in the clouds, although there was sun coming through well in the distance. Datalink showed airports near Rangeley reporting lower ceilings than earlier.

But the real killjoy for Plan A was the terrain display on the moving map that surrounded Rangeley in bright red for miles. This meant that at my current altitude there was no way I’d get past the hills and into Rangeley. Combine this with the fact that not only did the ceilings not appear sloped, it looked like I wasn’t even going to maintain 2000 for long and Plan A looked pretty grim.

Some interesting psychology here is that the bright red on the terrain map made it easy to let go of Plan A because it was a graphic and objective assessment that we were just too low to get in VFR. That’s a great way to combat the temptation of “it might get better if I press just a bit further on.”

After a clearance, we topped the clouds at 4600 with no ice. We got the cruise clearance while still over the undercast, but were able to make it a visual. The clouds broke up not five miles from the airport.

Now, this flight could have been done legally and practically in an old 172 equipped with an ADF and a timer (Rangeley has an NDB approach from RQM). But it wouldn’t have been as cut-and-dry to ditch Plan A and it would have been far more nerve-wracking executing Plan C if it was needed. Having never been into Rangeley and having a passenger with me, I’m not sure I would have tried Plan C without the TAA data. And without the Plan C option, I’m not sure I would have taken the flight. So often the go/no-go is a cumulative thing.

Thinking Inside the Box(es)

When you look underneath the NextGen hype and the promise of expanded capability, you’ll see that it’s almost entirely about data: better position identification, exchange of traffic warnings, weather in the cockpit, etc.

If you’re flying a TAA, you have much of this data right now. The controllers don’t share in the high-tech wealth, so there’s only so much you can do with it, but you can still leverage what you’ve got to your advantage.

As pointed out in case two, cruise clearances become extra useful when paired with IFR GPS. They grant you pilot’s discretion on descents and your choice of approaches. While you can’t quite “self-vector,” you can work the IAF that bests suits your needs without asking.

Even if you’re getting vectored, you might see a problem long before ATC does. Suppose you’ve just been assigned a vector to intercept the final approach course. A quick glance at the moving map will show almost exactly where that vector will put you and how much time you’ll have to get established. If you don’t like the looks of it, then suggest a new heading to the controller based on what you see. I’ve never had such a request refused.

But, like the negotiation over central New York, explain why you’re looking for the change and what information you have at your disposal: “Portland Approach, Cessna Eight Two Seven, on my GPS it looks like I’ll intercept five miles out. Could I fly 300 to cut in a bit closer to PEATT?”

Also remember that TAA flying isn’t solely the realm of glass-cockpit singles or carbon-fiber personal jets. By the FAA’s definition, a Piper Cub with a portable GPS that’s got a moving map is a TAA. Use whatever cockpit tech you have to its maximum potential. TAA isn’t just about what gadgets you have. It’s a state of mind.

Jeff Van West does his best to still enjoy the scenery when he isn’t pushing pixels in the cockpit or on screen while creating the latest IFR.