It’s odd, considering how closely pilots and air traffic controllers must work together, that each tends to be unfamiliar with the other’s working conditions. At times it may feel like a marriage in distress, neglecting each other’s needs while trying to run the household of aviation.

Speaking from personal experience, two major keys to a good marriage are communication and empathy. What’s likely to happen if both parties express their needs, limits, and concerns effectively? A smoother operation with fewer surprise twists will hopefully result.

It’s true that controllers are required to contend with a massive pile of their own regulations, charts, and procedures that may not be obvious to pilots. On the flip side, most have very little knowledge of what goes on in the cockpit. They wouldn’t know a mixture knob from a flap switch. The FAA is taking steps to remind controllers that those on the receiving end of vectors have a lot on their plate too.

Semi-Automatic Speech

Let’s talk first about, well, the act of talking. Controllers are known for their rapid fire verbal delivery of complex instructions. However, we need to balance speed and clarity. When it’s busy, the last thing I need to be doing is repeating myself because I’m getting flustered and mushing words together.

During a challenging situation, tension can cause a person’s natural speech pattern to hike up both in speed and pitch. Unchecked, their inner Mickey or Minnie Mouse gets unleashed. A squeaky, rattled controller doesn’t inspire confidence in anyone, especially the pilots under their watch and the coworkers at their side.

Lots of controllers—myself included—develop two distinct voices over time: their normal conversational tone, and a distinct “controller voice” for the radio. No, it’s not quite as drastic as Bruce Wayne’s gravelly vocal gymnastics when he dons his black cowl and becomes Batman for a romp around Gotham City. However, we do tend to measure our tone and diction to ensure we come across strong and clear on frequency.

It’s something that takes practice. My first ATC trainer gave me a great tip: “The crazier the traffic, the slower you need to speak.” It was effective advice. If I protract my speech while deliberately issuing an instruction to one aircraft, I can be thinking of what I’m going to tell the next aircraft. Also, the slower I speak, the less likely I am to be misunderstood. That’s a win-win.

Now, “slow” is relative. To a fresh pilot, even a reduced ATC speech cadence may feel like a hailstorm of words. The fact is, we do have to convey a lot of critical information in a short period of time. However, we’re supposed to be mindful of how clearly we deliver it.

Portion Control

Of course, effective communication isn’t just about clarity. It’s about the content of the message, and how well it can be retained and processed by the recipient. Too much information, too quickly, is a breeding ground for errors.

Imagine ATC instructing, “Descend and maintain 3000. Fly heading 020. Reduce speed to 150. Report the airport in sight, nine o’clock, eight miles. Traffic at your three o’clock, four miles, converging course, Skyhawk, 3500. Verify ATIS Mike.” Did you get all that? That’s a lot, right? The controller is simultaneously asking you to descend, turn, slow down, look for both the airport and traffic (in opposite directions). Oh, and report that you’ve got the right ATIS.

Some pilots may be able to process that transmission just fine. Some won’t, and “some” just doesn’t cut it. Controllers need 100% of their instructions to be followed. Therefore, it’s better to chunk them down into smaller, easily digestible bits that stand a much higher likelihood of being properly received and digested.

New controllers are trained to not issue more than three instructions at once, and stick with a max of just two if possible. Headings, speeds, and altitudes are all issued as numbers. The more numbers you pile into one transmission, the more likely they’ll get missed or transposed.

Let’s return to that earlier transmission. This time, the controller simply says, “Reduce speed to 150, then descend and maintain 3000.” Soon after comes a second transmission: “Fly heading 020. Airport nine o’clock, seven miles. Verify you have information Mike.” Lastly, he follows up with, “Traffic, three o’clock, three miles, converging course, Skyhawk, 3500.” It’s much easier to follow in smaller bits that relate to the current circumstances.

Like Crystal

Keeping our transmissions compact and easily understood isn’t just common sense, it’s part of our regulations. Some examples are obvious, such as recommended use of “Tree”, “Fife,” and “Niner” in lieu of three, five, and nine. However, there are a few others you may not hear as frequently.

FAA Order 7110.65, section 2-4-18—Number Clarification—says: “If deemed necessary for clarity… controllers may restate numbers using either group or single-digit form.” For example, if I’m assigning 17,000 to an aircraft, I can issue, “Climb and maintain one-seven thousand, seventeen thousand.” I’m required to state the “one-seven thousand”, but I back it up with the optional, group form: “seventeen thousand.” Plain English reinforces the instruction.

If I have two aircraft with similar call signs on my frequency, 7110.65 2-4-15 (a) says “Notify each pilot concerned when communicating with aircraft having similar sounding identifications.” Example? “November Eight One Two Charlie Delta, Approach. November Niner Two One Charlie Delta is also on this frequency. Acknowledge.” We’ll say the reverse for the other aircraft. We don’t want one guy taking another’s clearance. Really bad things not only can, but do happen.

Clarity is expected for the ATIS as well. Section 10-4-1 in the general facility guide—FAA Order 7210.3—states: “Before transmitting, the voice and/or text message must be reviewed to ensure content is complete and accurate…” and “…the specialist must ensure: 1. The speech rate is not excessive, 2. The enunciation is of the highest quality, and 3. Each part of the message is easily understood.”

One morning, as I opened up the tower, I was fighting a nasty cold. After I recorded the opening ATIS, a pilot requested his clearance. He added, “I’ve got the ATIS, but I can’t make out the winds. Are they two-two-zero at fifteen, or three-two-zero at fifteen? I can’t understand the guy.” I checked the recording. My phlegm-addled voice was so muddy, I could barely make it out myself. After making quick use of some tissue, I apologized and quickly corrected it.

Slam Dunking

As a pilot, you’re expected to adapt to new circumstances. However, even clearly understood, bite-size, regulation-compliant ATC instructions can complicate—or even overwhelm—a pilot’s life if they’re ill-timed or contradictory.

This is especially true during the descent phase. To get your airplane down from cruise flight to touchdown is largely an exercise in energy management, balancing your speed and descent rate, while adjusting aircraft configuration. A stable descent leads to a stable approach, ideally culminating in a stable landing. That stability largely comes from being able to stay ahead of the airplane.

However, the FAA has noticed a trend where controllers are pushing pilots beyond reasonable expectations. Aircraft are winding up too high, too fast, and/or too close to their destination airport, and end up going around. An airliner that’s still 5000 feet AGL on a five mile final isn’t likely to stick that landing, no matter how sweetly ATC asks. Between physics, passenger comfort, and company policies requiring the aircraft to be stabilized by a certain altitude and distance from the threshold, it’s just not happening.

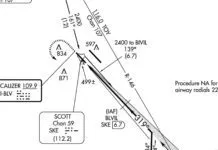

This unfortunate situation can often start well before your destination. For instance, if you’re flying a Standard Terminal Arrival (STAR), you must hit specified geographic fixes at predetermined altitudes and speeds. It creates a smooth, predictable descent profile.

What if ATC vectors you off that STAR? Once you’re “off the rails,” it’s difficult to see what’s coming. Your routing or arrival runway gets changed. Altitude and speed restrictions get assigned. You’re trying to stay on top of all this while flying the airplane, handling your cockpit procedures, and listening for the next clearance. That struggle directly impacts your ability to manage that energy for a stable approach.

The FAA is making a dedicated effort to educate controllers about aircraft characteristics and pilot workload. We recently received two separate briefings on this in one month. Their point is simple: give the pilots a fighting chance to get down, whether they’re flying heavy metal or a flight-school trainer.

Ground Effects

Imagine, after a long flight to an unfamiliar airport, you’re finally about to touch down. As you negotiate a vicious crosswind, sink into ground effect, and fight for the centerline, would that be an opportune moment for a controller to ask, “Say parking?” Of course not.

Short final, initial landing rollout, and takeoff roll are all critical phases of flight. The pilot doesn’t need any distractions. He must focus on bringing his aircraft to rest or getting it airborne. An ATC instruction then can be an annoyance; at worst it can cause a dangerous oversight or slip. On aircraft with thrust reversers or reversible pitch props, it can be hard to even hear ATC with roaring engines slowing the bird down.

Controllers are urged to avoid giving any instructions during these times. The 7110.65’s rules concerning Runway Exiting (3-10-9) include the note: “Runway exiting or taxi instructions should not normally be issued to an aircraft prior to, or immediately after, touchdown.” Even once arriving aircraft have slowed to taxi speed, controllers should keep any required taxi instructions simple until the aircraft clears the runway.

That said, sometimes a controller may absolutely need to talk to you during those critical moments. An unexpected situation may occur forcing them to change their original instructions.

Say you’re starting your takeoff with a specified heading and a confused student pilot veers into your path. Knowing you’re busy, the controller will say, “N12345, no need to respond. Fly runway heading instead.” Fly the airplane, comply with the instruction, and give a read back as soon as you’re comfortable.

The FAA’s effort to educate controllers about cockpit workload and aircraft performance will hopefully result in smoother sailing. In the off chance you get left high and dry or overtasked by ATC, ask for the ATC facility number and tell them what happened. Unless an issue is brought to someone’s attention, it’ll never get fixed. As always, the best approach is a cooperative one.

A View from the Other Side

The FAA’s and the airlines’ eagerness to educate controllers about the pilot side goes beyond briefings and videos. They want them to get a firsthand glimpse of the action in the cockpit.

In the halcyon days before the September 11th, 2001 attacks, it was easy. Controllers could just “flash and dash,” showing their I.D. badges at the ticket counter and sliding into the cockpit jumpseat on an available flight. After 9/11, that was nixed due to security concerns, and a valuable educational tool was lost along with it.

A few years ago, it was reinstated with more restrictions. There’s no more “flash and dash.” Officially called Flight Deck Training, every flight has to be pre-coordinated with the airline far in advance, all outbound or inbound travel legs must be conducted within an eight-hour work day, and it can’t be used in conjunction with vacation time (aw, shucks). We’ve also got to fill out a report about our experience.

It’s been a valuable experience for many controllers. There’s nothing like riding up front, watching the pilots do their jobs. Questions get asked and fielded by both sides. The controllers can see how a seemingly simple ATC instruction or clearance can translate into a lot of crew coordination and aircraft reconfiguration.

As a pilot myself, I enjoy offering a similar experience, but on a smaller scale. I’ve occasionally rented a Cessna and taken new ATC trainees up for a flight in the local area. I let them handle the plane a bit, look for traffic, spot landmarks, and generally get a feel for what they’re expecting pilots to do. Then we’ll get in the traffic pattern and see how they do keeping up with all the sequencing instructions from their coworkers.

Both controllers and pilots tend to take pride in what they do, and enjoy sharing the experience with others. If you ever want a tour of your local ATC facility, just ask for the facility’s number at the local FBO. We want to build a strong working relationship with our local aviators.

On the flip side, if you’re in a position to offer a flight to a controller, I haven’t met many that’d say no to the opportunity. Show them what you do, why you do it, and the workload involved. While you’re flying with a controller beside you who’s familiar with the airspace, you can pick their brain, get some concerns off your chest, and gain some new perspectives.

Tarrance Kramer likes to give pilots a fighting chance while working traffic out in the Midwest.