Pilots want ways to mitigate bad weather. The Coded Departure Route (CDR) is one of the least-known such tools in GA, although it’s been available since 2007. The AIM tells us, “CDRs provide air traffic control a rapid means to reroute departing aircraft when the filed route is constrained by either weather or congestion.” So, if you’d rather not wait, a CDR might be for you.

A CDR Is…

CDRs originated in the spring of 2000 after horrible weather during the summer of 1999 extensively disrupted air service. In response, the FAA collaborated with the airlines to develop canned alternate routes called coded departure routes for the summer of 2000.

CDRs worked so well that GA pilots wanted them. The FAA concurred and issued Advisory Circular 91-77 in June 2007 spelling out how GA pilots can use CDRs.

A CDR can be used with or replace a SID. Although there are 27,800 CDRs, only around 3000 keep you out of the flight levels and don’t require advanced equipment. Yet, compared to only 507 conventional SIDs, CDRs offer far more route alternatives.

CDRs are part of the Severe Weather Avoidance Program (SWAP), a formal plan to minimize the effect of severe weather on traffic flow. This program is normally implemented to provide the least disruption to the ATC system when flight through portions of airspace is difficult or impossible due to severe weather.

There is no magic in CDRs. It is much faster for controllers to consult their CDR route database to find you an alternate route than to cobble together a safe departure route when thunderstorms, turbulence or heavy traffic get in the way. Your CDR can be rapidly generated, communicated to controllers, coordinated, fed into FAA computers and issued to you as an abbreviated clearance with minimal controller workload.

A CDR offers a standardized departure when the only alternatives are to accept a ground delay or refile a new route to avoid the adversely affected airspace.

A CDR contains a full-route clearance for ground-based navigation (in a world moving to RNAV). A CDR might have a completely different—and longer—route, and you should plan accordingly, especially regarding fuel.

Flying a CDR requires one of three different equipment classifications, or codes. Code 1 is for basic navigational routes. Code 2 means you can fly routes with RNAV SIDs and/or STARs, and Code 3 means you can fly Q-route segments and/or pitch and catch points.

On departure, a pitch point is a waypoint used as a transition from a departure procedure or the low altitude ground−based navigation structure into the high-altitude waypoint system. On arrival, a catch point is the opposite, taking you from high- to low-altitude ground−based navigation.

All aircraft should be able to fly Code 1 CDRs, and most RNAV-equipped aircraft should be able to fly at least those Code 2 CDRs with compatible altitudes. Code 3 requires high-altitude capability.

Are You CDR Capable?

CDRs are generally the purview of high-dollar flight management systems found in aircraft with lavatories and galleys. Unfortunately, the databases used in navigators commonly found in aircraft with piston or small turbine engines have no provision for CDRs.

Garmin said that CDRs are not defined by the FAA in the standard ARINC 424 data format and thus are not coded by Jeppesen, making them unavailable to Garmin’s navigators. Garmin added that because of this lack of compatible data coding, CDRs are not currently planned. From the never-say-never department, if ARINC 424 ever includes them, then perhaps they’d end up in Garmin navigators.

This, however, is not a deal killer. Indeed, even a C-172 can file and fly an appropriate CDR.

You might consider putting “CDR capable” in the remarks section of a flight plan to tell ATC that you’re familiar with CDRs. But, doing so tells them that you have all the possible CDRs available, and that you can fly any of them, even the ones using Class A airspace. While this may be true for some sophisticated aircraft, little of GA would meet those requirements. If you do, though, the tower can issue you a CDR on the spot if necessary, and it is this flexibility that makes CDRs so useful.

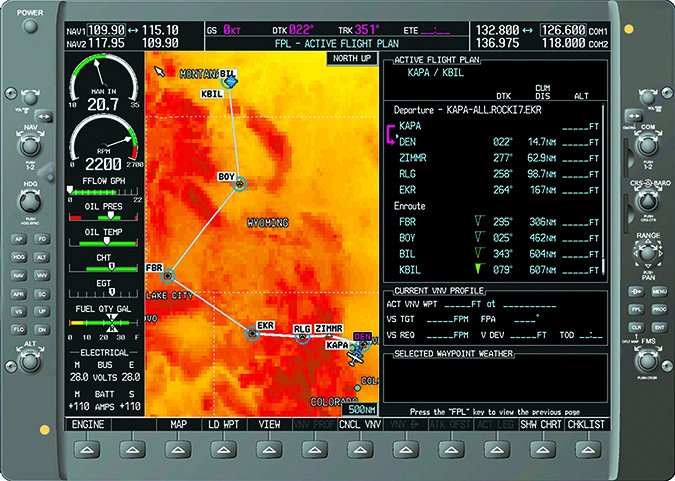

This ad hoc nature of CDRs may be beyond reach for the majority of general aviation without a lot of nav data entry at the last minute. However, if you simply think of a CDR as an alternative routing option to the normally preferred route, you can still plan and file a specific CDR. You can then fly it by just copying the CDR fixes into your navigator’s flight plan as we’ve done in the G1000 illustration, below.

Finding CDRs

Go to www.fly.faa.gov. Click Products, then click the Route Management Tool link. This takes you to the Air Traffic Control System Command Center page. Click on, “CDM Operational Coded Departure Routes” for the CDR query tool. Enter as little as you want, such as departure and destination airports, or even just your departure airport, to see what’s available. The database is updated in step with the 56-day IAP charting cycle.

There is often more than one CDR for a city pair. Each CDR has a route identifier consisting of the departure and destination airports, a letter for the direction of the departure and a number. For instance, ORDLAXN1 means Chicago O’Hare to Los Angeles via the North 1 CDR.

Armed with just this information, you could file a flight plan using the name (reportedly, read on) or fixes of the CDR and be on your way. However, there are planning tools that incorporate CDRs to make your life easier.

Planning and Filing

In a quick check, I found that DUATS, iFlightPlanner.com and Fltplan.com support CDRs. Other tools probably support them as well but I didn’t look further than these.

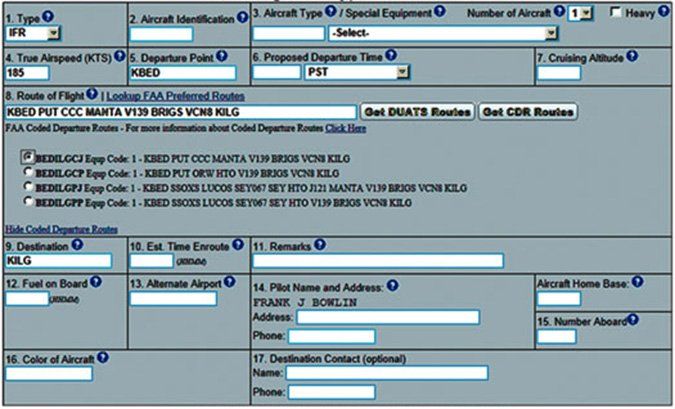

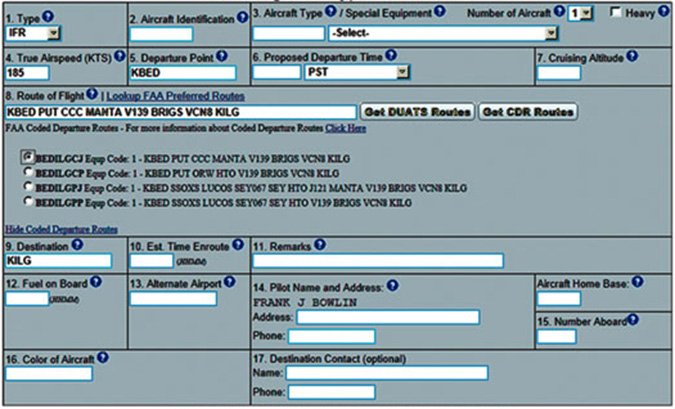

DUATS provides CDR support that’s easy to use. When you file a flight plan, a button will find the CDRs for those cities. Click the one you want and it will fill in the route of flight field. Drop the leading K for airports when filing any DUATS domestic flight plan to prevent an annoying message that tells you the system dropped it for you. AC 91-77 says you can file a complete route from the CDR name, but I couldn’t get DUATS to take one.

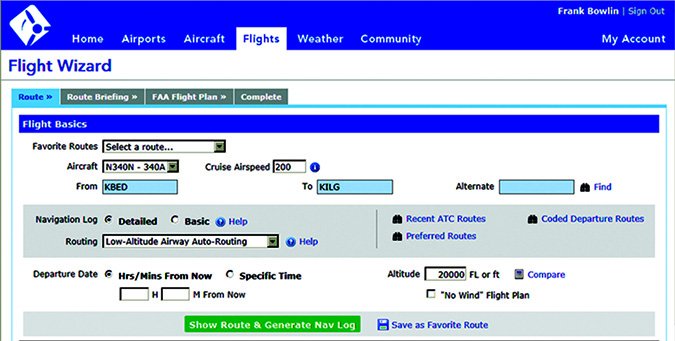

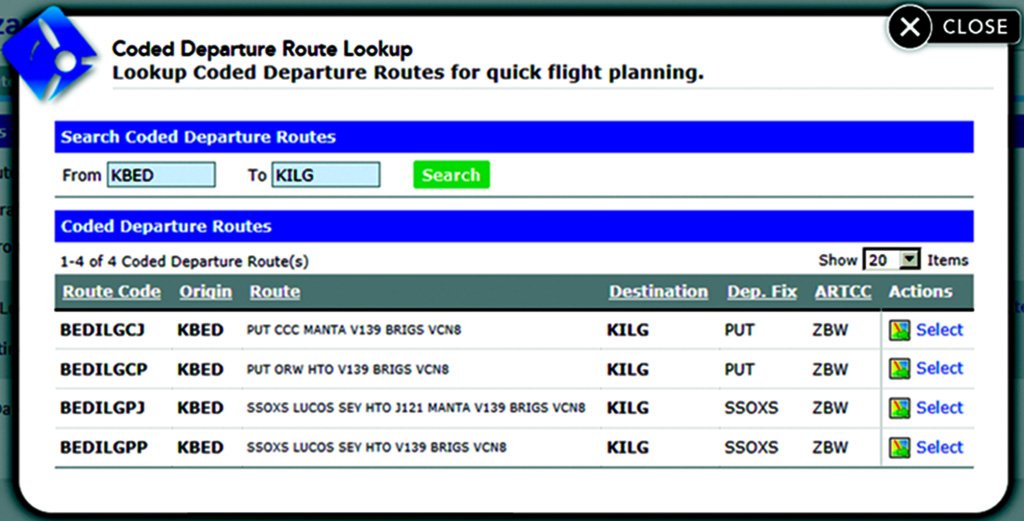

To work with iFlightPlanner, I used a flight from Bedford, Massachusetts (KBED) to Wilmington, Delaware (KILG). In the middle routing section there is a dropdown box that offers nine different routing methods. I started with low-altitude routing so I could compare the lengths of the alternative CDRs.

CDRs for the route are shown by clicking on “Coded Departure Route.” Click “Select” on the right side of the CDR you want. The route is created according to the fixes of the CDR and you can proceed normally.

I chose a flight from Denver’s Centennial Airport (KAPA) to Billings, Montana (KBIL) to see how FltPlan handles CDRs.

Start in Flight Planning and click “Create Flight Plan.” Enter your airports, select “IFR Domestic Format,” then click “Press Here When Done.” Scroll down until you find the Coded Departure Routes button. An active button tells you there’s at least one CDR.

The CDRs on this route aren’t as usable. CDR -E1 contains the EEONS3 SID. Can you fly that? Back on the flight plan page, scrolling down you can view SID charts. EEONS3, RIKKK2, YELLO7, SOLAR2 and FOOOT2 are turbojet only, leaving CDRs -E6, -S6 and -W6. CDR -E6 has J13 in it and -S6 requires FL230 on the departure—both obvious no-goes in our 172. This leaves the -W6 CDR, but even that has a SID altitude of 16,000 feet and a top grid MORA of 15,600 feet, ruling that out as well. It doesn’t look like our 172 can fly a CDR from Centennial to Billings.

Dynamic Weather Routes

DWR is a search engine that continuously and automatically analyzes in-flight aircraft in enroute airspace to find time- and fuel-saving corrections to weather avoidance routes. Every 12 seconds, DWR computes and analyzes trajectories for enroute flights. Route adjustments are simple reroutes like those typically used manually today. Courtesy of NASA, these will be coming soon to an ARTCC near you.

An active CFII in Florida, Fred Simonds likes waiting on the ground far less than flying a longer route. See his web page at www.fredonflying.com.