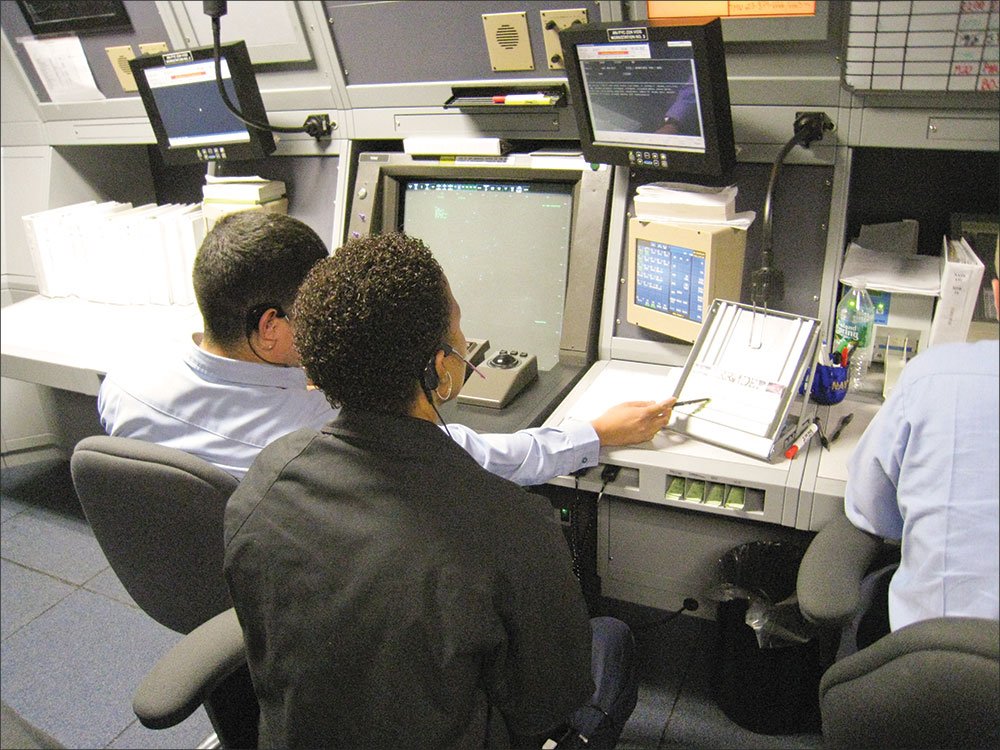

Controller staffing levels are on the mend. But the surge of newbies may mean an erosion of some ATC fundamentals and a permanent culture change.

Here’s a sobering stat: Odds are that an air traffic controller you’re talking to at any given moment has less than four years of on-the-job experience. That shouldn’t be a surprise if you’ve been following this issue for the past few years.

However, there’s a thread in this newbie-controller storyline that’s hasn’t seen much press: These new controllers are being trained in a different environment than the bulk of their predecessors. It seems to be changing the culture of ATC and the ability of these new controllers to improvise on the fly. It’s perhaps a subtle change, but one worth watching.

The Backstory

Dial back 30 years ago, and President Reagan has fired essentially the entire controller workforce when the union goes on strike. This results in a hiring binge (and near chaos for a while until the new staff gets up to speed).

Fast-forward to 2007 and many of those controllers are eligible for retirement.

At the same time the FAA imposes new work rules and contract wrangling gets intense. Many controllers decide it’s not worth sticking around and attrition of experienced staff hits 3.75 controllers a day. Over 1600 controllers retired in FYs 2007 and 2008 combined—better than one tenth of the workforce.

But the FAA and the controller’s union (NATCA) got square on the bargaining table and hammered out a deal. By FY 2009, retirements had dropped to 520 and stabilized in the 500-ish zone. In those same rough years of FY 2007-9, the FAA was pumping as many folks through the academy and into developmental training as practical. The number of development controllers—those doing on-the-job training but not yet certified—who washed out doubled. That too has trickled back down to a more reasonable level.

All through this process, we saw issues with inexperience and an increase in errors. But the system didn’t come to a screeching halt. Training controllers might have been losing hair faster and gone through a lot more rolls of Tums, but planes weren’t colliding every other day. Safety of flight was probably not on the line no matter how much some folks wrung their hands on it.

But smooth operations and convenience were. And they still are. Some of the changes are fallout from the changing of the guard and some are casualties of technology.

RNAV Versus Improv

We’ve spoken with veteran controllers both close to retirement and recently cashed in, and hear a common complaint: The new controllers can’t vector as well. This smacks of ageist “Back in my day …” but when we dig deeper, we come up with a legitimate instigator: RNAV and GPS.

“They’re all being brought up on RNAV arrivals and departures,” one Boston Approach controller told us about the younger staff at his facility. “So they don’t vector traffic unless it’s an overflight.”

That’s not a problem—until there’s a problem, like a thunderstorm rolling across that arrival route. Now the controller has to get creative with traffic flow. The problem isn’t that they can’t vector—they know how to do it—but that they aren’t as proficient. They’re not as good at it because they don’t do it all day, every day. “It’s really a problem if they start in the fall, so they have months on the scope before the problem first crops up.” That would be in the summer, when the storms start rolling through.

We asked NATCA about this and they declined to comment on it directly. But Steve Hansen, Chairman of NATCA’s National Safety Committee, points out that there have always been SIDs and STARs, so the RNAV versions are changes of paradigm rather than something completely new. But there are more of these arrivals being created in more places and there is less vectoring. He says there’s also a problem in that there’s no standard phraseology or procedures for taking aircraft on and off these RNAV arrivals.

NATCA has a work group on this trying to define some standards.

Complicating matters is that many of these RNAV arrivals and departures were designed more for noise abatement than smooth traffic flow. Those circuitous routes make improvising a new flow that much harder. Altitude plays in here. The old arrivals to Boston crossed the coast at 6000 feet. Now they cross at 10,000.

We’re also told by some folks who don’t want their names or facilities mentioned that there’s pressure to keep planes on the noise-abatement routes as long as possible even in the face of weather.

A related phenomenon may be brewing at a more common, GA level. While controllers can still vector aircraft onto RNAV (GPS) approaches, it’s common to “point-and-shoot” by just sending them direct to an IAF and letting the automation take it from there. Will this also erode general controller skill in vectoring? Time will tell.

What this means for you as the pilot is to keep a close watch on the vectors you’re given. If it doesn’t make sense, or even if you can see a slight adjustment may be better, speak up. It also means that if you’re moving through airspace around a busy ‘burg when weather has the controllers pushing transport-category traffic around, be extra alert.

By the Book

Every facility has its local procedures to expedite the flow. However, one veteran commuter airline pilot in the Northeast told us: “You just don’t hear people asking for the old shortcuts, or controllers offering them.” Procedures are more by the book. “Where we used to be told to report over the lighthouse, now it’s always ‘10-mile right base.’ “

Is this a problem? Not per se, but if the lighthouse was actually a bit closer than the standard base-leg arrival, it’s a small hit to efficiency. Those add up. It also represents an underlying culture change in ATC. You may have to work a bit harder to get an out-of-box request granted.

You also may have to explain yourself more. Even though clearances for an IFR climb to VFR conditions exist in the book, new controllers may not have any idea what you’re talking about when you ask for one. The same with cruise clearances, which can be a power tool for a GPS-equipped aircraft on a marginal day.

New controllers may not have a good sense of different aircraft. This is where your role as pilot-in-command truly matters. One facility had two standard departures: heading 290 to 3000 feet for turboprops and heading 140 to 5000 for light jets. A Falcon called in and got the 290 to 3000 assignment because the controller thought it was a turboprop. The pilot accepted, despite knowing that was an unusual departure clearance for that airport.

It wasn’t until the Falcon was heading west rapidly overtaking slower traffic ahead, that the error was realized. Remember what we said about reduced skill in vectoring? Apparently it wasn’t pretty. But then again, no metal got bent.

Ironically, some of the best service you see might be at non-federal contract towers. To work at one of these towers, you must have previous experience as a certified controller. Some of the “new hires” at these facilities have just retired from the FAA or the military with 25 years of time under their belts.

Does This Matter?

None of this constitutes a serious safety-of-flight issue. It’s more a harbinger of things to come. By 2014, 25 percent of the ATC workforce will be eligible to retire. By 2019, it’s expected that close to one third of the ATC workforce will be developmental controllers.

By Jan. 1 2020, we’re all supposed to be flying with ADS-B in the NextGen ATC of tomorrow. Will our reality in that world be an ATC system that leaves controller improvisational skill and creativity largely untapped and atrophied? Perhaps. As you fly down the road from now to then, don’t assume the voice on the other end of the radio knows what’s going on more than you do.

Jeff Van West is glad he’s not the one who must learn how to vector. He’s also the editor of IFR.

What, exactly, do you mean when you say, “error”?

There’s been a rise in operational errors (OE) in recent years. For example, the Boston Globe reported a rise in OEs of 81 percent since 2007. But what exactly that means depends on whom you ask.

Some veteran controllers will tell you it’s a real problem and it’s getting worse. Others will say the issue isn’t so much that there are more errors total, it’s that more of them are getting detected.

For 20 years, there’s been something called the Operational Error Detection Program at en route Centers. This is the so-called “snitch” that will automatically generate an alert for supervisors if separation is lost by even a 1/10 of a mile. In 2008, the FAA began rolling out the Traffic Analysis and Review Program (TARP) at the TRACON level. This peach of a system not only squawks for any loss of separation, but it even tells which section of the ATC regulations it thinks were violated. How nice.

This is at least part of the rise in OEs: infinitesimal violations that had always occurred but no one knew or cared about were now getting reported.

The problem is that TARP can detect a fault where 2.99 miles of separation should have been 3.00, while separation would have to drop to about 2.7 miles out of three before the average human eye can see it’s too tight. Controllers complained that it wasn’t fair to simultaneously push them to get the best throughput yet penalize them for errors too small for them to even see.

The other problem is that OEs requires retraining and recertification for the controllers before they can handle live traffic again. With such a load on training all the new hires already, this was unacceptable.

In response, the FAA created a new kind of OE called the Proximity Event (PE). Something could be labeled a PE if there was at least 90 percent separation (which happens to be 2.7 miles out of a required three), there was no wake turbulence issue and safety was never involved. The intent was mainly to stem the tide of OEs and resulting retraining required just because aircraft got a tad too close together on final. The PEs have a much lighter penalty; It might just be some computer-based training and you’re good to go.