The Aviation Safety Reporting System, ASRS, is a means of confidentially and anonymously reporting unsafe conditions—including your own actions—in aviation, generally without fear of FAA enforcement. Most of us are at least somewhat aware of the ASRS program, but few of us really understand how it works. This is an important program that is of benefit to aviation at large and potentially to us individually, so we should all understand what the ASRS system is, what it can do for us, and how to use it.

Detecting Unsafe Patterns

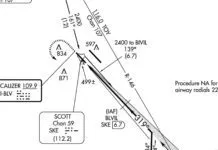

The catalyst for developing ASRS was—as is often the case—a tragic, preventable accident. On December 1, 1974, TWA 514 was inbound to Dulles Airport in IMC and turbulence. The crew misunderstood an ATC clearance they thought permitted them to descend to 1800 feet. However, that altitude was for the next approach segment, not their current segment. The Boeing 727 crashed into Mt. Weather with no survivors.

Addressed as an isolated accident, there would have been no reason to believe that something larger, something systemic, was going on. But there was.

The NTSB’s investigation discovered that a United Airlines flight crew experienced an identical clearance misunderstanding six weeks earlier and narrowly missed hitting the same mountain during a nighttime approach.

Here’s the glitch: The United crew reported the incident to the company, who issued a cautionary notice to all of its pilots. There was no means to share that information across carriers; so TWA never knew that a systemic fault was in place. That lack of communication proved fatal. Unchecked, more crashes might have occurred. Approach charts system-wide were modified to help prevent such accidents in the future.

Organization

The NTSB and FAA realized that pilots, controllers and other aviation professionals needed a confidential, non-punitive, voluntary way to share safety information.

Further, a neutral, respected third party had to run the program. NASA was the logical choice. The FAA funds ASRS and runs its immunity provisions. NASA sets policy and administers the ASRS, largely outside of FAA influence.

ASRS has been very effective. The reports pilots, controllers and others make influence FAA policy and procedure, stimulate corrective action, resolve issues, and draw attention to serious problems needing resolution at higher levels. The program has also proved useful in determining root causes of accidents and even identifying aviation product deficiencies and needed improvements.

Why Participate?

There’s no downside to reporting. Anyone involved in aviation is welcome to submit a report for any situation where aviation safety may have been compromised. Even if it was someone else’s safety, it might one day be yours. Your submission is voluntary, but encouraged. Your report could literally help prevent a future accident involving you or someone you know.

In aviation, we all look out for each other. It’s part of our collective safety net. If you can repair a tear in that net, you reduce risk for the entire aviation community. That is the underlying principle of the FAA’s new Compliance Philosophy, one element of which is helping to fix the problem. To this end, submitting an ASRS report is deemed cooperative and under the compliance-first priority, helping avoid enforcement. See “A Kinder, Gentler FAA?” in last month’s IFR.

An ASRS report is held in strictest confidence. Over a million reports in the last 34 years have been submitted and not one has been breached. This anonymity is achieved by stripping the report of the reporter’s identity and that of involved organizations. To prevent reverse-engineering into identification, dates, times and other identifying information are either deleted or generalized.

Get Out of Jail Free?

Your reward for making a report is the prospect of receiving a get-out-of-jail free card if you are later found to have violated an FAA regulation. That can only happen under certain conditions, and the details matter. Those details are spelled out in AC 00-46E as described in the first list in the sidebar.

The FAA offers ASRS reporters non-enforcement in 91.25, which says, “The Administrator of the FAA will not use reports submitted to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration under the Aviation Safety Reporting Program (or information derived therefrom) in any enforcement action, except information concerning accidents or criminal offenses which are wholly excluded from the Program.”

If criteria in the list are not met, certain factors can still mitigate enforcement; see the second list in the sidebar.

Quoting AC 00-46E, “The FAA considers the filing of a report with NASA concerning an incident or occurrence involving a violation of 49 U.S.C. subtitle VII or the 14 CFR to be indicative of a constructive attitude. Such an attitude will tend to prevent future violations. Accordingly, although a finding of violation may be made, neither a civil penalty nor certificate suspension will be imposed if [the criteria in the first list are met].”

In short, you strengthen your position if you busted a reg and filed a timely report. If you consult an aviation attorney, the first thing you’ll be asked is, “Did you file an ASRS report?” You want to be able to say, “Yes.”

Pay attention to the 10-day limit to report an incident. Don’t put it off. The FAA strictly applies this limit.

It is commonly thought that you can only file one report in five years. This is not true and causes pilots to avoid reporting smaller incidents waiting for “the big one.” Indeed, you can submit as many ASRS reports as you like. The FAA has to officially find that a violation occurred in order to trigger the five-year loss of immunity by a repeat offender.

How to File

While you can still file on paper, the quickest way is to file online. The second tab from the left says “Report to ASRS.” Hover over this tab to select whether you want to file electronically or download and print a form to mail. Be sure to keep a copy. If you mail your report, send it registered with a return receipt to prove that it was received. You will receive an electronic or written receipt that you should keep in your files in case the FAA comes a-knockin’.

To File or Not to File?

About 10 years ago, I was new to south Florida and all the complex airspace surrounding the many airports in close proximity to one another. I flew an Angel Flight into North Perry airport. On departure I got rattled by the many tall towers all seemingly right in front of me. I deviated to the left and inadvertently entered the Class C surrounding Fort Lauderdale. I then contacted Departure and he let it go. I did not file an ASRS report, but I wish I had because my error made me vulnerable to enforcement. In today’s less-forgiving environment, and with snitch software in ATC facilities, even the smallest deviations are noticed.

A good friend of mine, an excellent pilot, was handed off to New York Approach on an IFR flight plan to Essex County Airport (KCDW), in Caldwell, NJ. He was at 3000 feet. A few miles from KCDW, the controller told him to follow another aircraft at about his two o’clock. It was nighttime.

Being near the airport he interpreted the controller’s instruction as clearance for the visual approach which he’d been told to expect. He descended, but soon realized the preceding aircraft was not going to KCDW. He then informed the controller who vectored him to his runway. He later realized that the instruction was not a clearance for the visual approach so he shouldn’t have descended. The controller said nothing so the pilot thought his altitude bust slipped by.

Two and a half months later the pilot received an email from a FSDO manager stating that, “We are investigating a possible pilot deviation…en route to the Essex County Airport. You were assigned 3000 feet by ATC and descended below this altitude. Please complete the attached questionnaire and return as soon as possible.”

This is not uncommon. Just because nothing is said doesn’t necessarily mean it has gone away. If you have something unusual happen during a flight, file an ASRS report. It only takes a few minutes and could mean the difference between getting busted or simply learning.

In this case, the pilot and FSDO manager had a good conversation and the matter was dropped. It could have gone the other way. In that case the pilot would need to have promptly filed an ASRS report. Fortunately, the pilot didn’t get a Letter of Investigation, which is a far more serious matter.

Recently, a fellow instructor was with a student on an LPV approach into a tower airport. The weather was clear and there was no traffic. The controller requested a three-mile-final report. The instructor got distracted and they missed the call. Just after landing, Tower informed them that they had landed without clearance. Ouch!

In later discussion, my instructor friend and I believe the tower controller sought to use that call as a reminder that he had an inbound aircraft while he tended to other work. The pilot and the instructor both goofed. He filed an ASRS report, just in case.

Additional ASRS Services

Every ASRS report submitted becomes part of the ASRS database, the world’s largest repository of voluntary aviation reports from people on aviation’s front lines—pilots, controllers, mechanics, dispatchers, etc. The database is fully searchable, but to eliminate unnecessary searching, they also maintain 30 database reports on specific topics such as Altitude Deviations and Flight-Training Reports. These are updated according to need. Each canned report contains 50 pre-screened relevant reports.

And finally, ASRS electronically publishes a free monthly newsletter titled Callback. It’s a great, fast, fascinating read. The latest issue is titled, “It Could Never Happen to Me!” Can you relate?

Fred Simonds is an active Gold Seal and G1000-certified CFII in South Florida. See his web page here.