Of all the features of the modern Automatic Flight Control System (AFCS), perhaps the most useful is altitude preselect. It improves safety by reducing altitude busts and deviations. However, it can sometimes get you into trouble on the approach.

Background

Ever since Lawrence Sperry’s first autopilot in 1914, automatic flight control systems (AFCS) have continued to improve and add more features. According to legend, Lawrence used his invention to join the mile-high club. However, just like today, the autopilot can disengage at the worst moment. In one instance, Lawrence was a little late disengaging himself and there was a crash landing in the Great South Bay off of Long Island. Both Lawrence and his female “student” survived the “training flight” but somehow all their clothes were torn away in the crash. They were nude when rescued by duck hunters—who reported finding jaybirds, not ducks.

Altitude preselect (ALT SEL) might be the best feature to be added. It allows you to set your desired altitude and then select the mode for climb or descent. The AFCS will calculate the rate of closure on the altitude and adjust the capture point to smoothly round out on the desired altitude. Whether it’s climbing or descending at 500 feet per minute or 2500 feet per minute, the AFCS will calculate a smooth capture. Once the altitude is captured the Flight Director (FD) will provide commands to the autopilot (or pilot) to maintain that altitude.

(Note that less capable GA systems don’t round out smoothly, instead just capturing the altitude when reached. This results in a modest overshoot.)

I first encountered altitude preselect in 1976 at Sperry Flight Systems, but it existed much before then. Old patents show that both Sperry Gyroscope Company and Honeywell developed many autopilot altitude control improvements in the 1940s and 1950s. The first mention of “Preselect Altitude Control” was in a 1963 patent application by Sperry’s prolific inventor Harry Miller.

Functions

The altitude preselect display performs two functions. First, it serves as an alerter when approaching the selected altitude or deviating from the selected altitude. The alerting threshold for altitude-to-go is normally 1000 feet in most systems and the threshold for deviation from the selected altitude is normally 200 feet. Of course, the altitude preselect also tells the AFCS the target altitude.

Altitude alerters have been around for a long time even before altitude preselect. Part 91 operators of turbine-powered aircraft have been required to have altitude alerting capability since §91.219 was enacted in 1989. Originally the altitude preselect/alerter was a separate unit usually mounted near the center of the instrument panel. In the old days these took in synchro data and compared it to the synchros connected to the selected altitude display knob. Before digital avionics, it was amazing what was done with synchros and analog computations.

Of course, the altitude preselect/alerter has changed over time. Since around 2000, newer implementations for GA aircraft have eliminated the separate instrument and instead show the selected altitude above the altitude tape on the primary flight display (PFD). The altitude preselect AFCS mode also operates differently. The old AFCS such as the Sperry SPZ-200A and the Collins FD-109 had a Flight Director mode panel with an ALT (altitude hold) and an ALT SEL (altitude select) pushbutton. The nomenclature on the King KFC-250 was slightly different, but it operated similarly.

To hold the current altitude you would push ALT. If you wanted to set a target altitude for climb or descent, you selected the altitude in the altitude preselect window and pushed ALT SEL. After that, you would select the mode you wanted to climb or descend (initially just pitch, but later IAS or VS). Once the selected altitude had been captured, the mode transitioned to ALT.

Sperry had three AFCS modes: ALT SEL ARM, ALT SEL CAP (annunciated as VRT), and then ALT HOLD. If ALT SEL was not selected the controller still used the selected altitude for alerting. You could use ALT SEL mode for the climbs and descents, but you would not select it for a precision approach.

You might use the altitude preselect window to enter the DA for alerting purposes, but not push ALT SEL. Or you could set MDA for a non-precision approach and use ALT SEL to level at that MDA.

With the “old” AFCS system you could have only one active and one armed mode. For example, VS selected as the active vertical mode and ALT SEL armed. In the lateral axis Heading (HDG) could be the active mode and Approach (APR) as the armed mode. Once the FD determined the capture criteria had been met the armed mode transitioned to become the active mode.

Today’s Altitude Preselect

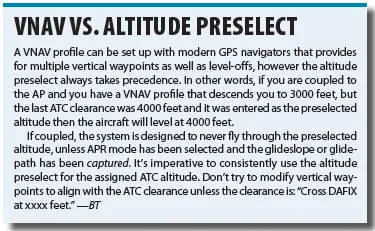

Today’s systems automate more mode selections and allow multiple armed modes. For example, it’s possible for altitude hold (ALT) to be the active mode, VNAV armed, and approach (GS) armed. This is useful for pilots to program a transition to an approach.

Today’s AFCS automatically arms altitude preselect unless the GS has been captured. The Collins FCS-65 was the first system to automatically engage ALT SEL mode when the preselected altitude was changed. Every professional flight crew I’ve flown with would, by reflex action, reach for the altitude preselect knob as soon as ATC gave them a new altitude. The automatic arming of altitude preselect makes the operation more straightforward and was happily accepted, except when infrequently that wasn’t what was wanted. The approach (APR) is one of those cases.

Intercepting GS From Above

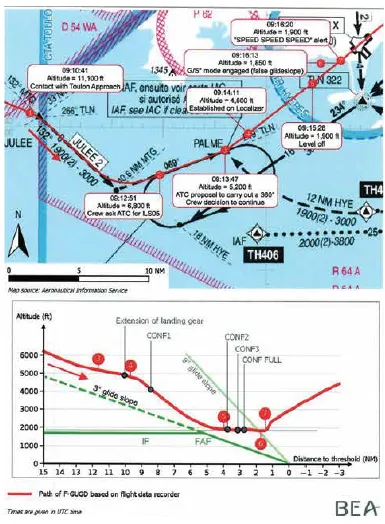

The French BEA investigated an incident on an Air France Airbus A 318-100 in December of 2019 that illustrates the disadvantage of having the AFCS automatically engaging ALT SEL. The illustration above is from the BEA report. The approach was to capture the glideslope from above (not a good practice but it happens) and most modern AFCS will capture from above or below the glideslope. The IF was at 1900 feet—also the missed approach altitude.

At point 4 the aircraft was established on the localizer but had not captured the GS. Since ALT SEL is automatically armed instead of capturing the GS the system started the capture of the selected altitude. By point 5 the capture was complete, and the mode transitioned to ALT. The aircraft leveled and by point 6 they had captured a false glideslope. The aircraft’s pitch changed from a nose-up angle of one degree to 30 degrees in roughly 20 seconds. A much fuller 16-page investigation report of this incident can be found online.

The Airbus Flight Crew Operating Manual (FCOM) describes a procedure to intercept the glide slope from above for an ILS approach once the airplane is established on the localizer. If followed, this procedure would have prevented the incident. This procedure consists of, with the AP engaged:

- Arming the APPR mode, if not already armed, arms the G/S (glide slope) mode.

- Selecting an altitude greater than the airplane’s actual altitude.

- Engaging the V/S (vertical speed) mode and initially selecting -1500 feet/min.

Arming the G/S mode arms the glide slope acquisition and means that the risk of Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) is avoided.

Setting an altitude above the actual altitude means that unwanted leveling off during the descent on the glide slope (or glide path) is avoided. If an altitude below the actual altitude is selected, the AP will capture this altitude unless G/S mode is selected.

This wasn’t a fluke. The BEA investigated two similar incidents preceding this one. Plus, many new general aviation AFCS including the Garmin GFC 500 would do the same thing. For example, the GFC 500 autopilot operation in the Flight Manual Supplement for the Textron Aviation S35 and V35 series states that for ILS approaches, the missed approach altitude should be set in the altitude preselect. In Garmin’s defense, this step is after verifying the airplane has captured and is tracking the LOC and GS. (Note that Garmin’s annunciation of ALT SEL mode is ALTS but the mode operates identically.)

Other Garmin Flight Manual Supplements are silent on where to set the altitude preselect for an ILS approach. It’s good to set the missed approach altitude in case of a go-around, but it must be in the proper sequence … after GS capture. As can be seen from the Air France experience if capturing the GS from above you must be doubly sure where the altitude preselect altitude is set.

A cardinal rule on ILS approaches when intercepting the glideslope from above is to never set the altitude preselect below the current altitude unless the GS has been captured. The same thing can happen when intercepting an LPV or VNAV approach from above. The difference is the inadvertent level-off and deviation away from the vertical glidepath will not lead to intercepting a false glidepath. It will just cause a glitch in the approach.

Intercepting GS From Below

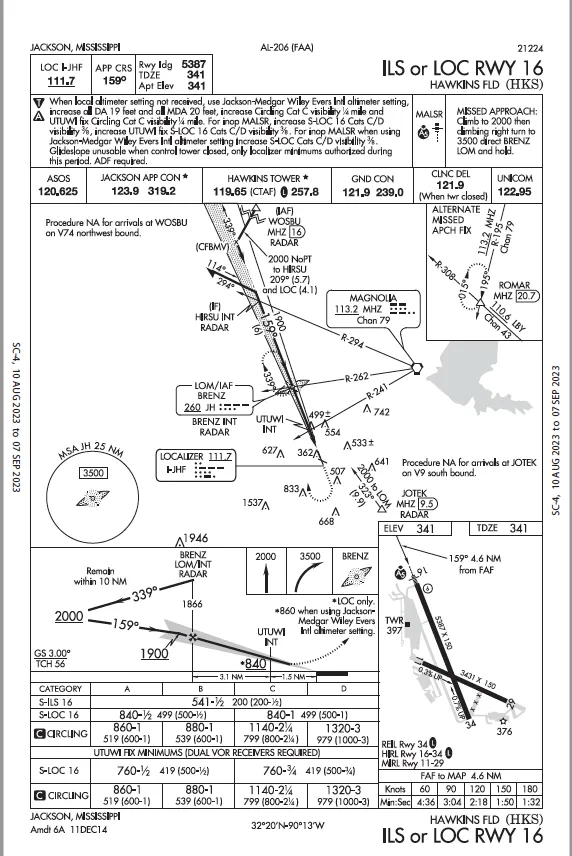

The automatic arming of altitude preselect is not an issue when intercepting the GS from below. The aircraft will be in level flight. ALT SEL will have been automatically selected while the GS is armed but as soon as the GS is captured and the aircraft starts down, ALT SEL is locked out. Look at the ILS RWY 16 at Hawkins Field (HKS) in Jackson Mississippi shown to the right.

The initial missed approach altitude is 2000 feet. If you set 2000 as the selected altitude when you are at 2000 feet, there is no vertical AFCS mode to trigger the AFCS to start down. Thus, there is no problem intercepting from below. However, if you are at 4000 feet nine miles out and have programmed a VNAV path to cross BRENZ at 1900 feet you shouldn’t be surprised when the aircraft levels at 2000 feet instead of continuing down to 1900 feet.

If you are managing the AFCS properly, the only thing that will start you down is when the GS has been captured which causes the ALTS mode to be canceled. Since 2000 is already set in the preselect altitude, it will be armed and set to capture if you select go-around.

One last note: If you are on a visual approach and decide to go around, climbing to the missed approach altitude could get you a phone number to call and a possible pilot deviation. Why? A visual approach is not an IAP and therefore has no missed approach segment. If a go around is necessary for any reason, aircraft operating at controlled airports will be issued an appropriate advisory/clearance/instruction by the tower. Reference AIM.

Annunciations

The best insight into what George, the autopilot, is doing is to check the active and armed modes. These will display at the top of the primary flight display (PFD). Lacking that, they display on the autopilot controller/mode selector. There is almost universal acceptance that the active mode is displayed in Green while the armed modes are in white. For the previous example, holding altitude would be displayed as a green ALT, VNAV would be shown in white as well as APR in white. Even though George can’t talk, the annunciations convey what George is trying to do. The lesson to be learned is if Lawrence had been a little more attentive to George rather than his student he wouldn’t have ended up in the water off Long Island.

ERROR: In Intercepting GS From Above, the bottom of the fifth paragraph says: ”…the AP will capture this altitude unless G/S mode is selected”. It should read: “… the AP will capture this altitude unless G/S mode is engaged/captured”. Selecting (arming) APR will not prevent the autopilot from capturing an altitude above the glideslope.

The ALT SEL mode cannot become active and level the aircraft after capturing the glideslope. Once another mode, such as Go-Around, is selected, ALT SEL will function “normally” again.