Altitude is aviation. From a simple paper airplane to the recently launched Artemis, anything that is above ground and moving has altitude and is essentially aviating. With altitude so important, how important is it for pilots to comply with altitudes, whether ATC assigned or from the regs or AIM?

Yeah, It’s Critical

Simple answer is that altitude is extremely important. The entire NAS has been designed and re-designed several times. It’s why you might get a pilot deviation if you’re a hundred feet off. Altitude compliance is one of the top five trending safety issues in the NAS right now. Some think it’s just an ARTCC issue or approach control, but it comes into play in the Tower environment as well.

Your ability to fly straight and level plays a major part in maintaining the correct altitude for your mission and as instructed by ATC for a specific purpose. Sure, there is an allowance for being off due to incorrect altimeter or rapidly changing barometric pressure, but if you’re off by 300 feet and the other plane coming at you is off by 200, you could be a little too close for comfort. Discretion is a big word when attached to altitude and should be respected.

In Air Traffic Control, our job is to sequence and separate on a first-come, first-served basis, lacking other priorities. We have our basic rules for separation for any given flight, and we’ll use a number of tools to meet those separation rules. Every ATC environment (ARTCC, Approach, Tower) has its primary concerns.

In Tower, I absolutely must have runway separation based on the types of aircraft involved. This is why I work “runway out.” Altitude separation in the VFR Tower environment is built in by way of “Traffic Pattern Altitudes” (TPA), SOPs, and controller discretion. We don’t really use “altitude your discretion” calls in the Tower due to the Bravo airspace right above us, and TPA. Most of the time it’s “at or above.” If we do have two aircraft at the same altitude and converging, (VFR/VFR) we may give them a quick “suggested” turn, in lieu of a climb/descend, because we don’t have lateral separation rules for VFR traffic.

In the Approach and Center environment, controllers sit in front of radar screens and their primary role is to separate the targets on the screen. For them, many altitudes like MVA, MOCA, etc. are written in SOPs, LOAs, and baseline the 7110.65. Their main focus is to separate IFR flights, with an absolute basic separation minimum of three nautical miles laterally and/or 1000 feet vertically (below FL410).

Which do you think is easier? It’s a simple matter of distance. 1000 feet vs 15,840 feet? It’s way easier to have a pilot descend or climb 1000 feet than to achieve three miles laterally if both targets are IFR. For VFR/VFR separation, it’s simply, “Don’t hit each other” but ATC might offer suggested altitudes or headings.

ATC can also do “stacks” if we need to. ARTCC/Approach utilize this when putting airplanes in holding. “Rack em and stack em!” Below FL410, only 1000 feet is needed to separate vertically. Theoretically, if an ARTCC controller has FL300 to FL400 to control, and needed to hold 10 airplanes at one intersection, they could do it. Does this happen a lot? Not really. See last month’s excellent article, “Stacking ‘Em,” by my associate, Tarrance Kramer.

Pilots Discretion

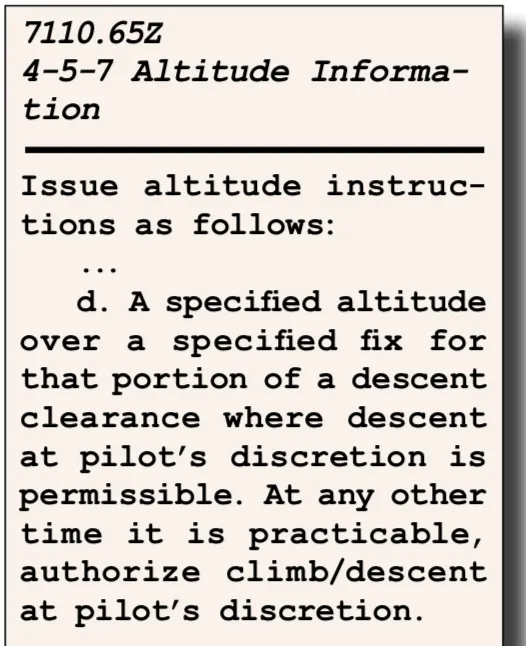

All right so let’s move on to the kicker, “Altitude your discretion.” Why does ATC offer “discretion”? The same reason you would use a hammer to help build a house—it’s a tool used for efficiency any time it is useful. This instruction can also be used in all the ATC environments, however I’ve seen it mainly used in Center and Approach. Section 4-5-7. d. of the 7110.65 mentions, “Issue altitude instructions” using “a specified altitude over a specified fix for that portion of a descent clearance where descent at pilot’s discretion is permissible. At any other time it is practicable, authorize climb/descent at pilot’s discretion.”

We don’t have a lot of fixes that we descend people to in the VFR Tower environment. There can be many reasons a Tower controller needs to limit altitudes, but the main one I personally use is for transitions while I have pattern traffic.

In the radar rooms, Center and Approach controllers will use pilot’s discretion a lot. Centers utilize pilot’s discretion (PD) often when aircraft are on an arrival. Pilots tend to want to stay high as long as possible to save fuel. As long as ATC has no one in front of you or lacks a specific need to descend you, they would issue this to give pilots the option.

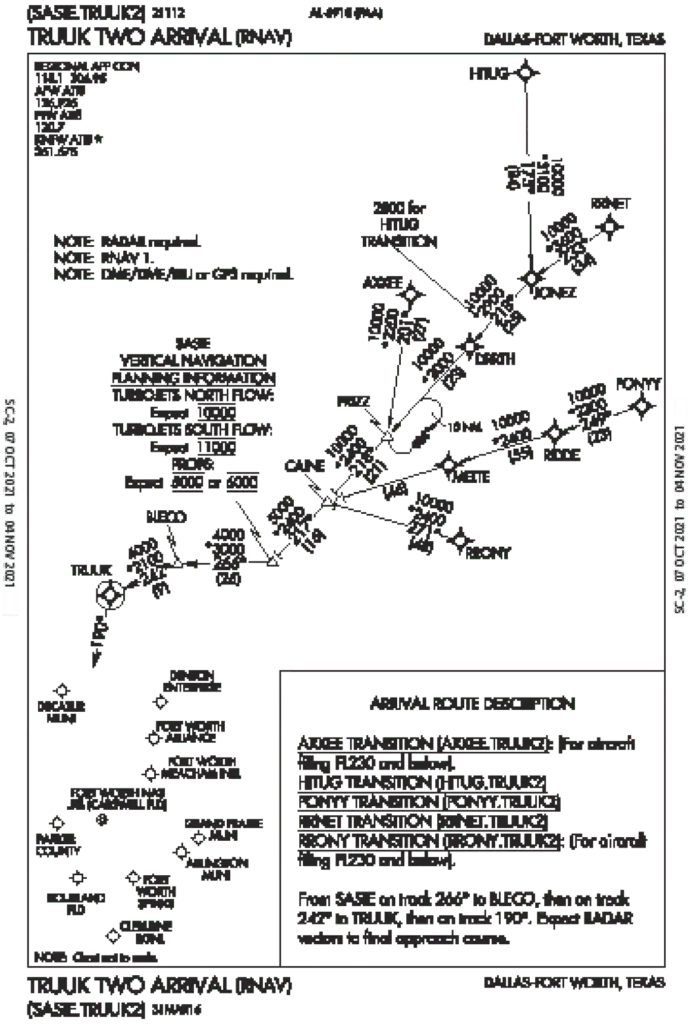

A friend of mine flies jets near DFW, so he frequently gets the TRUUK2 Arrival. Most of the time upon checking in with Fort Worth Center (ZFW), they will assign him direct PONYY and give him a pilot’s discretion (PD) descent to FL240. Reading the arrival, he either has to cross SASIE at 10,000 feet or 11,000 feet, so he sets up his VNAV accordingly. After checking on with the new frequency, he gets “Cross SASIE at and maintain 10,000 (or 11,000 depending on flow).” Rarely does he not get a PD on the arrival. ATC giving pilots this instruction allows for a little extra flexibility on the pilot’s side, and a slightly reduced workload on the controller. PD means they don’t have to keep going back to you to step you down.

Okay, let’s level off and talk explicitly discretion. “Descend at pilot’s discretion, maintain xxx,” or “Cross DAFIX at and maintain…” ATC understands this generally assumes normal performance of the subject aircraft airplane, but it does not mean the airplane will always use the rates the AIM says it will. When I was in the Air Force, I watched plenty of F-22 pilots take this and run with it comedically. They would be five miles from the fix where they had a crossing restriction 20,000 feet below. ATC would kindly remind them, then the show started. Yes, F-22’s can easily lose 20,000 feet in five miles—even one mile. They just go straight down.

Obviously in the civilian world, most jets/pilots can’t fly this profile and wouldn’t even think about it. A note in the 7110.65, 4-5-7 states; “The pilot is authorized to conduct descent within the context of the term “at pilot’s discretion” as described in the AIM.” “Well, what if I get to the crossing altitude a mile or so before the fix?” Honestly, I would recommend being within a few hundred feet of that altitude, within a mile of the fix/intersection. If you’re flying a jet, it happens pretty fast anyway. If you make a crossing instruction, advise ATC immediately.

What’s the phraseology for other instances? What’s the proper readback? My general rule of thumb for answering this is simple: Unless you’re familiar with other phraseology, you’re always safe to reply with the instruction verbatim. “Descend to FL210. Pilot’s discretion to 15,000. Altimeter 29.92.” Just add your callsign to a verbatim readback. “Climb to FL300. Best rate through 250.” Same thing.

Anything with an altitude will need a hard readback, so you can just say it back as you heard it. Easy enough. What if you switch frequencies before you start your “pilots’ discretion” decent? When you check on with the next frequency, repeat the instruction again. “Center, N12345, FL400, PD to 250,” or “N12345, FL400 for 300, PD to 210,” or whatever applies to your scenario. Keep it simple, and repeat mostly as it was said to you.

But I’m VFR in the Class Bravo?

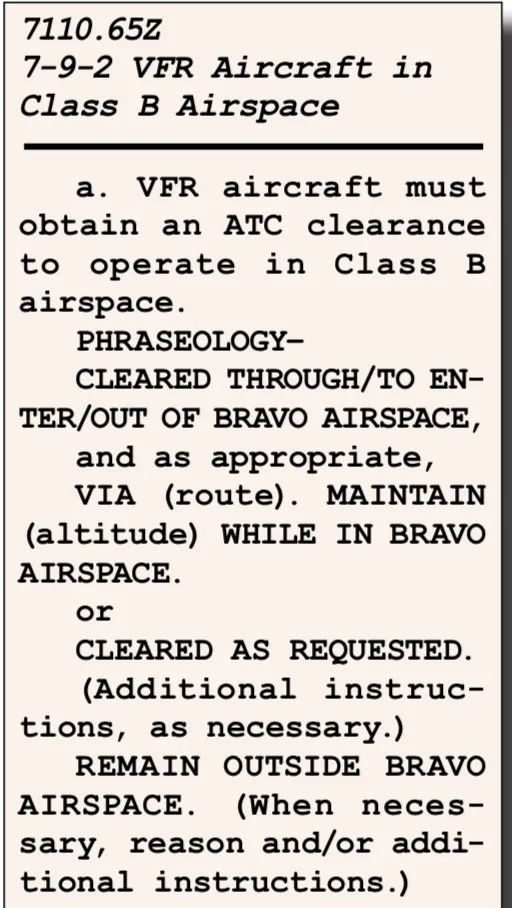

By reader request, let’s touch on altitudes to be flown while VFR in Class Bravo airspace. Remember that Class B is a Class B for a reason—it’s busy. There is no altitude to transition Class B airspace without hearing the magic words, “Cleared into Class Bravo airspace.” One thing I’ve heard far too often are pilots trying to continue on their way, but requesting Class B clearance while flying VFR, yet the approach controller is already very busy with IFR traffic in the area. Pilots end up clipping the Class B without clearance and get deviated. Plan accordingly. My tower is near a Class B and we are required to tell pilots to “remain clear of Class B airspace” whenever they request flight following. A flight following squawk and radar identification is not a Class Bravo clearance.

So, what altitude should you be flying in the Class B when VFR with a clearance to enter? You fly what ATC tells you. If you’re not on flight following, and are requesting clearance to transition or enter a Class B, they will most likely give you a squawk code. With that code input, the aircraft will be “tagged up” on the radar screen with callsign, type, destination, and requested altitude.

Based on traffic, they will tell you what altitude they can give you. “Cleared into Class B airspace at or below (or at or above) xxx feet,” or if they have just enough space you may be given a hard altitude, “Cleared through Class B at xxx altitude.” Maybe now you’re thinking, “Wait, I’m VFR? Why am I being assigned a hard altitude?” Because you are in Class B airspace and any ATC facility controlling Class B is required to separate all aircraft, even VFR aircraft. To change altitude after being issued a “maintain,” you would need permission. Being able to maintain that hard altitude correctly is one reason why student pilots require an endorsement from their CFI to enter.

Assuming you get a clearance and an “at or above/below” instruction, it’s pilot’s discretion to choose the best altitude for their route of flight consistent with that constraint. In this instance, you could change altitudes within the bounds of the clearance without notifying ATC. If you’re flying northwest and ATC gives you, “at or below 8500,” that narrows it down for you to 8500, 6500, 4500, etc.

But what if they give you “at or below 7500” going northwest and you want to stay high? If you plan to go back up after transitioning, 7500 would be acceptable while in the bravo. Don’t forget that you don’t necessarily have a free pass into other airspaces such as Class D airspaces below the Bravo. Verify with approach and/or plan to avoid any altitude that puts you into that airspace. Despite most Class B ATC facilities having LOAs or other agreements with the Class D towers in the area, I would recommend you never assume you have permission into any other airspace without ATC telling you. Use good judgment at all times.

Altitude Selection

Maintaining correct altitude, observing and abiding by the level off, and staying ahead of the airplane will minimize the chance of being called out by ATC. Most ATC requirements are to make sure that pilots comply with their altitudes and sometimes ATC’s requirements too. ATC is not the police to those requirements, but a lot of them line up with our job. Now go practice straight and level!

Elim Hawkins makes it his mission to promote best altitude practices, flying or controlling.