While even the classic aircraft typically have at least a portable GPS on board, going IFR can mean relying on something like a localizer or (gasp) a VOR to get to a runway. If it’s been a while since using these, don’t forget that there’s more to know than tuning, twisting, and following the needle. You’ll need to manage stuff like Victor airways (got it), VOR checks (fuzzy on those) and just possibly, timed approaches to deal with (oh, great). And just like any flight, getting organized in advance is key.

The Other One

A friend just retired from solo flying and turned over to you his beloved Cherokee 140, complete with hangar. Since it’s staying at Northeast Ohio Regional and he can still fly it with you as PIC, he was happy to give you a great package price. This allows you to budget for a full avionics upgrade. All you’ve gotta do is ferry the plane from Ashtabula, Ohio, to Aurora, Illinois, where the new stuff gets installed.

Good thing you’re familiar with the Cherokee and its dual VOR/LOC receivers; the departure’s marginal VFR will degrade to IFR along the way. You consider postponing, but going today lets you keep the shop reservation and get home by car tonight. So you plan a good ol’ fashioned VOR route to a station near the destination and see that there will be some zig-zagging due to the dearth of Victor airways until western Ohio. And there’s a slight jog to the south to bypass Cleveland’s busy airspace. So you file: JFN CXR ACO MFD REELS FBC V8 JOT

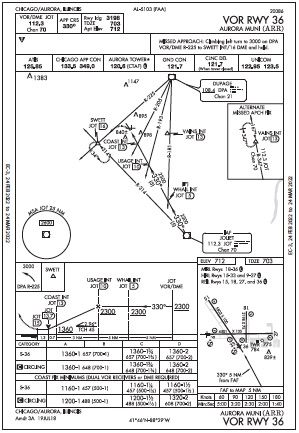

The most convenient alternate is DuPage (KDPA) with the local TAF calling for 900-5 for most of the day, with similar weather expected at Aurora. There, a curious approach awaits: VOR 36. Curious because you vaguely remember learning these initially before transitioning to an RNAV-equipped club plane.

Weren’t the VORs supposed to be gone like, last year? Far from it; along with the safety net of VORs reserved for long-term use (the Minimum Operational Network), ILS and LOC approaches are still advertised throughout the system daily. And, well-trafficked stations like JOT (and DPA, as well) aren’t on the list of VORs tagged for shutdown, at least not in the current phase running through 2025.

With this temporary downgrade to pursue sole ownership, you’re back in classic approach mode, so here goes. This approach has just one IAF, the JOT VOR/DME (the last fix on your route). From there, there’s no procedure turn, just an easy 15-mile straight-in from JOT. Could this be the VOR approach you’ve dreamed of? Just cross JOT at or above 2300 feet and you’re on the final course of 330 degrees, with no further descents until the FAF, USAGE.

Another bonus: The lower minimums of 1160-1 are easily accessed with the dual radios by identifying COAST intersection on the straight-in to Runway 36. Oh, wait… You actually want to land on 33, not 36. The former’s the primary backup to 9/27, 5503 feet with PAPI. By contrast, 36 is the little-used runway at 3198 feet, and its condition is a bit rough to boot. What’s the deal?

Circle vs. “Circle”

Just to confirm, the final approach course of 330 degrees is 61 degrees offset from Runway 36’s official magnetic heading of 01 degree. The IAP is also just two degrees offset from Runway 33’s course of 328 degrees. So why isn’t this called “VOR 33” or “VOR-A”? The root cause requires digging back to the archives of 1988. The Jan. 28 issue of the Chicago Tribune announced various expansion proposals for KARR.

Curious indeed. Seems that the original VOR approach for Runway 36 (which never got longer) simply remained. Technically, then, landing on 33 instead of 36 on this approach requires circling MDA. That makes the dual-VOR minimums 1200-1. It’s just 40 feet higher to “circle,” and you’re comfortable as long as the visibility is at least one mile for the small sidestep to the left to line up for 33.

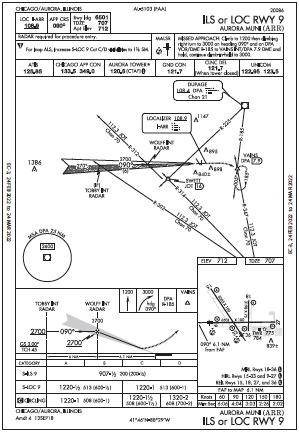

Stepping back to the charts, how about just using the LOC 33 with its lower minimums. Again, there’s no procedure turn and it also starts at JOT. It’d be perfect, of course, but it’s NOTAMed out of service.

There’s the ILS 9. It goes to the standard 200-½ and one of the nav receivers has a glideslope. But the northwest winds won’t allow it … or can this work? When the lower mins of an ILS become necessary, it might be worth considering a small tailwind component. (See “The Wind at Your Back,” IFR, July 2016). The straight-in ILS is 907-½; the LOC, 1220-½. With the winds at KARR shifting to 310 degrees, 15 knots, the tailwind component for Runway 9 would be about 10 knots.

There’s no guidance in the slim Cherokee 140 handbook for tailwinds. The single landing-distance chart (with notes including “no wind,” “maximum braking” and “short field effort”) shows about 475 to 550 feet for landing and rollout for weights between 1950-2150 pounds. You could triple 550 feet and still have plenty of runway. But you really don’t have anything to base that on, and you don’t relish the thought of maximum braking or mustering “short field effort” on a day like this.

Okay, check circling minimums for the ILS: 1220-1, similar to the straight-in LOC. That’ll get you on a left-base-final for 33, provided the weather is good for that. But it’s also 20 feet higher than the COAST fix MDA for the VOR 36 and would require more of a circling maneuver than the VOR 36-land-33 plan. So you decide on the latter, knowing that Du Page’s north-facing ILS approach is just a few minutes away.

Lucky Check

The plan works great as expected with “cleared as filed” to JOT before starting up on the ramp. Now, there’s one more brain teaser on the Cherokee’s IFR checklist that catches you off guard—the VOR receiver check.

AIM 1-1-4 is worth saving for bedtime reading, but there’s user-friendly instruction under, of all places, §91.171, “VOR equipment check for IFR operations.” This prohibits using VORs unless the receivers have been “maintained, checked, and inspected under an approved procedure” or “operationally checked within the preceding 30 days, [and] found to be within the limits of the permissible indicated bearing error set forth in paragraph (b) or (c) of this section.”

It also clarifies the dual-VOR check in item (c), which doesn’t require the airborne procedures in (b) like a visual checkpoint to overfly at least 20 NM from the station, on an airway “at a reasonably low altitude,” whatever that means.

The weather’s good enough to depart VFR, but you don’t have time to sort this out in the air. Lucky for you, the previous owner had logged a ground check right there at KAZY regularly for years, but the last was a few months ago. How’d he know where to check it? The list starts on page 405 of the East Central Chart Supplement. Interesting there are only three in all of Illinois and Ohio’s longer list includes a ground check of JEF at Northeast Ohio Regional. Funny how you never knew that in the three years you’ve been based there, but it never came up, until now. The regs allow for a bearing error of ± four degrees and the receivers easily pass.

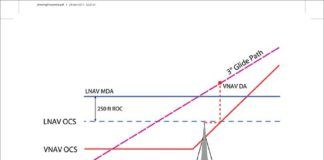

The flight goes smoothly and, backed up with a tablet GPS, you confirm a direct track to JOT, still wishing the weather would favor the ILS/LOC. Here’s why: You have dual VORs for the lower MDA, but you don’t have DME, so the VDP at JOT D13.7 and MAP at JOT D15 aren’t available to you. In fact, you’re stuck with the five-mile timetable (you know, bottom right corner) and timing for an estimated 90 knots groundspeed, which would be 3:20 on the timer and Category A approach mins.

The next lucky break is that the weather is as promised and you see both runways in under three minutes, allowing you to achieve that “circle” to 33 while switching your sights to VMC. It occurs to you on the taxi to parking that it wouldn’t hurt to keep that number 1 VOR receiver with glideslope, just in case you find yourself choosing from a VOR-LOC-ILS menu.