During a heated conversation have you even crossed the line? Have you been told you did? Assuming so, unpleasant things happen after crossing that line you know shouldn’t be crossed. Same goes for approaching a runway that you shouldn’t be on. The only difference in this case is FSDO and a lot of other people hear about it.

Definitions

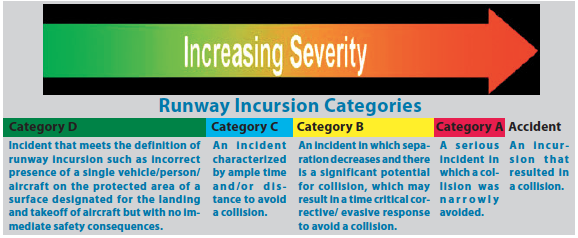

Despite all the training and programs out there, runway incursions remain on the rise. The FAA reports that from FY 2021 to thus far in 2022 we’re already up about 15 percent. Crossing the line when you’re not supposed to is a big deal and is in the top three increasing trends over the past couple years. This can cost lives and is completely preventable. Pilots might think that runway incursions are just, “oops I crossed that line on the ground.” The FAA categorizes runway incursions into four intensities of seriousness.

What is a runway incursion? Per the FAA website, a runway incursion is “Any occurrence at an aerodrome involving the incorrect presence of an aircraft, vehicle or person on the protected area of a surface designated for the landing and take-off of aircraft.” Pilots, non-pilots and ATC can be responsible for anyone who is on a runway they aren’t supposed to be on.

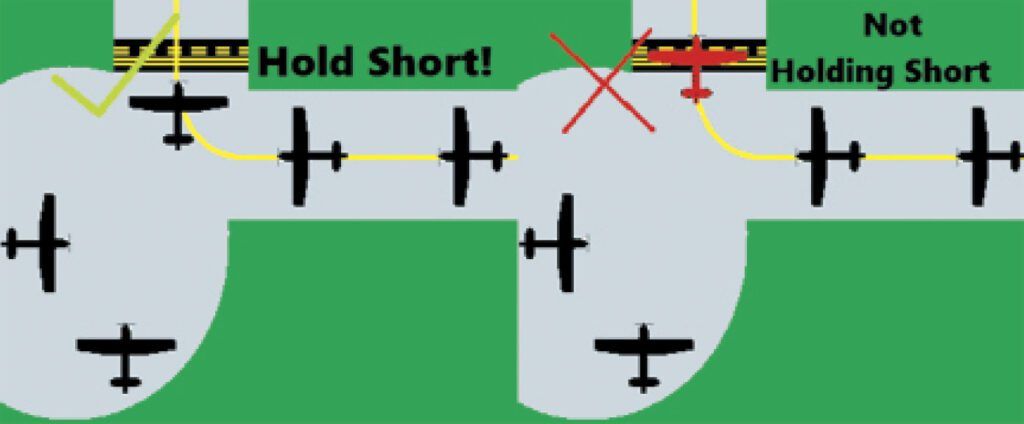

From the tower we can see the hold line, and whether it appears an airplane has crossed that line. Since most hold-short lines have the signs next to the line, Towers use this reference first. With binoculars, I can tell if an airplane crosses the line. Of course, if someone crossed the line a landing pilot might also call that out.

Anything passing the hold-short line, known or unknown, is bad. But the farther you go onto a runway (or closer when landing) without permission increases the severity. ATC has four categories of incursion severity—Category A, B, C, and D, with A being the worst and an accident was “narrowly avoided.” The categories become less severe to Category D for an incursion that had “no immediate safety consequences.” I’ve personally seen many Category D and C events, a handful of B events and two A events. Any of these get everybody’s blood pumping.

Causes?

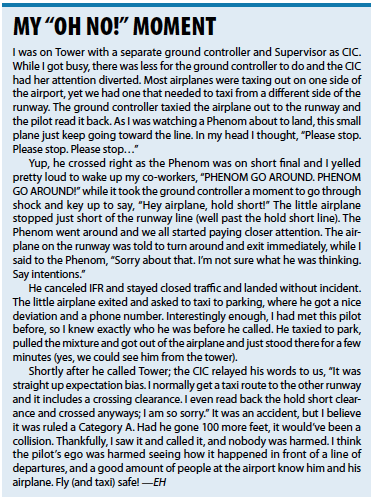

Many different things can cause a runway incursion. Hazardous attitudes, ignorance by pilot or ATC, expectation bias, etc. Personally, I’ve experienced pilots having expectation bias more than anything else. “Oh, I thought you said…” right after reading back “holding short.” All accounts taken, runway incursions start to happen when there is a failure in communication or nonexistence of situational awareness on the part of at least one party—human error. As I’ve stated before, we all make mistakes and there is literally and physically no way we can stop making mistakes, however we can mitigate. We’ll talk about how in a bit.

Human error can even be expanded to include “who.” Wait, who is responsible for the runway incursion? On the ATC side, I’ve had several incursions that were the actions of the PIC, but when those PICs are solo students on their first or second solo, it goes further than to just blame that one person. In these cases, I would place some blame on the CFIs. Before students’ solo, CFIs have a minimum checklist of things that the student must understand and handle properly. Most of us remember emergency procedures, reading back the assigned runway with any clearance, and also reading back hold-short instructions. While some of those students figured out what they did really quickly and started crying on frequency, it’s a small price to pay compared to the latter.

There are several different ways a controller might cause a runway incursion. Maybe I forgot to assign you a runway or assigned the wrong runway, or maybe I told you correctly, but you read back something different that I didn’t catch. Perhaps I gave you a traffic call of an airplane going to another runway and you thought it was a sequence to follow.

While a small number of runway incursions come from ATC, it’s enough for us to have recurrent training on it and continue to increase our situational awareness. Believe it or not, we can actually get an “atta-boy” which is a record of a controller doing anything to assist the NAS to prevent runway incursions or many other types of non-standard events. My take away is to verify, and to verify again.

What Can We Do?

So, what can ATC and pilots do to help prevent this? There are plenty of things ATC can do to reduce the percentage of our statistical blame. First, I just keep my binoculars handy.

It’s somewhat common for pilots to line up to the wrong runway, particularly with parallel but offset runways. Sadly, this can turn into a mid-air collision before it has a chance to become a runway incursion. We can see pretty far with the binoculars, enough to see if you overshot or are coming in close proximity to the wrong airplane. Our radar shows your track and track history, so we can see that way as well.

If you ever have ATC repeatedly asking for a read back, it’s because they need to hear the magic words (mainly exactly what they just told you). Any clearance involving a runway (or taxiway for my helicopter friends), must be read back with the runway/taxiway. If you read it back, but out of instinct and didn’t really hear what was said, ask to verify the clearance.

Another thing I’ve said a lot, “N12345, it appears you are lined up to Runway (number).” This one generally has pilots double check their heading and location, and helps to prevent an incursion. I have another airport in close proximity to mine, so coming from a certain direction, pilots can mistake the other airport for mine. As for airplanes on the ground, we have a good general sense if you’re over the line from our view in the tower. We’ll start looking closer at airplanes that don’t give the correct readback.

Pilots should know the runway hold short signs and markings. While we’re focused on runway incursions in this article, going on to a movement area without permission is very similar and is called a “Surface Incident.” An example would be taxing to park or to the runway without a clearance from ATC.

Back to the runways, and assuming your radios are working, speak clearly. This one applies to controllers as well—speak as clearly as you can so things are understood without question. If you can’t hear or understand something, ask ATC to clarify. We do the same thing when we don’t hear pilots well. This might seem simple, but it goes a long way in reducing runway incursions and the expectation bias that often precedes it.

I also recommend concentrating on situational awareness. Consider a personal sterile-cockpit rule on the ground and in the pattern. If you’re confused or lost, say so. As the story in the sidebar goes, your ego getting hurt is a small price to pay to potentially save some lives and be safe. Last, understand that pilots and even ATC are pieces to a much bigger puzzle. These are just my simple recommendations to keep in mind. Whatever you do, please fly safe and let’s get these incursion numbers down.

Hold Short or Go Home

This article is intended for anyone operating on an airport surface. As controllers, we hear the words “runway incursion” a few times a week. Critical phase of flight may be defined as “approach, landing, take off roll, rotation, and initial climb,” but honestly the phase “taxi” and even “after landing” should be on that list as well, especially at bigger airports. ATC might get annoyingly insistent at times, requesting a read back of a clearance or verification of runway, but it’s only going to keep happening until we can get this trend under control.