When conditions are down to 200-½, the search for approaches and alternates with better weather can take some time. Options are few on a day like this, even if you’re comfortable flying down to mins. And even when finally selecting the airport and backup, you’ve gotta check the NOTAMs for the airports, airspace and procedures—and probably dig up the NOTAM-to-English dictionary, or its closest FAA equivalent.

OTS is U/S

It must be Monday. The first glitch of the day drops in before the second cup of coffee: The flight plan, filed on Saturday, needs amending. While it’s marginal VFR in Ainsworth, Nebraska, the destination, Brainerd, Minnesota, is socked in along with most of the state. The three-hour direct flight in your 140-HP low-wing will also leave less-than-acceptable reserves given the weather, so plan on landing somewhere on the way with 1.5 hours remaining. Instead of diverting off-route to a bigger city like Fargo, you’ll stop right along the way. It’s just 2.5 hours to Fergus Falls, 84 miles west of Brainerd. Einar Mickelson Field (named after a local WWII pilot) has the services you seek along with ILS and RNAV approaches to multiple runways.

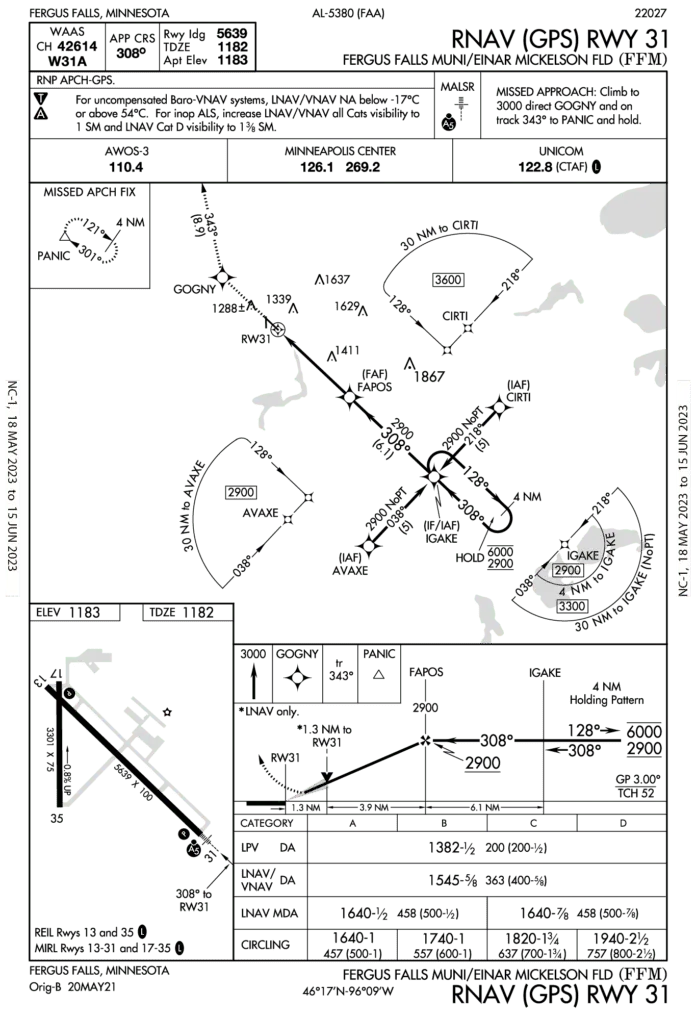

Just before amending the flight plan, another glitch came up. You saw the ILS 31 is NOTAMed out for a few hours. Fine—if you arrive before it expires, go RNAV. There are LPV minimums you can use, and you prefer those anyway. But if that first notice didn’t get your attention, some of the others did: “RWY 31 RAI LGT U/S” for most of the year. “RWY 35 RWY END ID LGT U/S” for about six months. “NAV ILS RWY 31 NOT MNT” for a few weeks. And, “RWY 31 PAPI U/S” for the next two months.

U/S? Unusable, Unsafe, Unsatisfactory? Perhaps it’s all or none of the above, depending on how you look at it. But technically, U/S stands for “Unserviceable,” according to the latest version of FAA Order 7930.2, Notices to Air Missions. Isn’t there a NOTAM for “OTS” that means “Out of Service?” Well, there was. In a textual explanation of recent changes, some NOTAM contractions have been swapped out to align with ICAO terminology. And to clarify, if you will, examples of NOTAMs in the order indicate that when spelled out, the term “Unusable” is followed by an operating limitation, like when use of a navaid is within a given distance or altitude: “NAV ILS RWY 12 LOC UNUSABLE BEYOND 4DEG RIGHT OF COURSE.”

At any rate, if the ILS goes back online today, it remains “NOT MNT,” which stands for “not monitored” or “unmonitored.” The approach is available, but be aware that (per 7930.2) loss of signal integrity won’t trigger an automatic shutdown, so it’s all on you to watch it. Anything better on the field? Not really. There’s an LNAV-only to Runway 35, which is okay for the northwest winds, but minimums are 1560-1 and it’s a 3301-foot runway without a PAPI. And, that runway’s end lights are also NOTAMed out for a few months. The LPV for 31 is definitely a better option with the same minimums as the ILS, 1382-½. Now it’s down to two runway NOTAMs: RAI and PAPI lights are “U/S.”

Give It a Whirl

Here’s where the Inoperative Components Table in the Terminal Procedures Publication kicks in. Luckily, your EFB (current data, of course) has a documents menu where you cleverly stashed the Inoperative Components Table file for quick reference. If two lighting systems for 31 are out of service at the same time, this table also confirms that the highest penalty for a single component applies. So it will be ¾ SM for the LPV, LNAV/VNAV and LNAV. Now that your two favorite lighting systems—lead-in and runway end—are dark, what is left? Pilot-controlled runway lights still work, so that’s good. The PAPI works, too. Two-light or four-light PAPI? Four-light on the left (thank you, airnav.com). All these little details, even when all the lights are working, definitely help avoid confusion or delayed action at DA.

The outages certainly had you considering going elsewhere, but most of the airports in the area are too low for approaches, alternate minimum rules notwithstanding. And Fergus Falls is holding steady at 300-1. In the end, Fargo is at a safe 1000-5, so it is the best alternate and would still leave you with an hour of fuel. Already 45 minutes behind schedule, you depart as soon as possible.

Again, it’s Monday, so a big mass of rain will move in close to your ETA of 5 p.m., and that’s sure to push the vis even lower, although ceilings are forecast to improve to 2000 feet by late afternoon. There’s still time to go and stay ahead of the precip forming to the southwest. When permitted, fly direct to the nearest initial approach fix (AVAXE) for the RNAV 31.

Finally, things get ironed out and the direct route’s approved. From your perch at 9000 feet, you can see a broken cloud layer ahead with tops around 7000 feet, and you see the bases are higher than expected, 4000 feet, on the descent towards AVAXE. The on-board NEXRAD shows scattered light pockets of rain ahead, and Center points out an area of moderate precip southeast of the runway while clearing you for the approach from 2900 feet. You acknowledge, but then get busy turning inbound at the next fix, IGAKE.

It’s still smooth, but when established, the rain gets more intense and the clouds darken. Although you thought you accounted for a 15-minute lag on the NEXRAD and avoided the small but yellow image of a cell to the west, it did creep into your approach path. Where to?

It’s perfectly legal (and safe) to begin a missed approach beforethe DA or MAP, so long as the courses and altitudes remain in compliance with the procedure. A climb to 3000 feet on the inbound course of 308 to GOGNY—about three miles out—are the first two steps, easily achieved from present position. But that means flying closer to the cell than you’re comfortable, at least as far as you can estimate from there.

Coulda, Shoulda

Power up and hope you don’t penetrate it at 3000 feet? Maybe get lower to continue the approach beneath the cell and land. Or if you can’t, go missed as prescribed? You can actually see the south half of the field through big gaps in the clouds. Great that it’s better than reported and even circling LNAV MDAs will now suffice. But that dark rain ahead could reduce visibility, and don’t forget about the lighting outages.

You’re still two miles from FAPOS and can stay at 2900 feet rather than descend on the approach if you want to safely miss here. Maybe you can continue visually, break off to the left to avoid the cell, and swing into a wide right base-to-final for 35. An approach clearance to an untowered airport doesn’t need to specify a circle-to-land, but you’re not thinking about that.

A sidestep to 35 is an option, as conditions are now well above circling MDA. Favor left of course in anticipation, and there are no obstacles within the traffic patterns for either runway. That would’ve worked if you didn’t lose sight of the runway in the rain, though. So staying aligned with the 31 straight-in, you continue up to 3000 feet and activate the leg to GOGNY. From there, a right turn followed by the appropriately worded “PANIC” for the hold.

There, it took two laps to catch your breath and wait for the heaviest rain to move out of the approach path. Then it took another lap to wait for ATC to get back to you, as all the other traffic in the state was busy doing the same. Once cleared for the RNAV 31 from the other IAF, CIRTI, the re-do was so much easier as the vis increased to two miles and the post-rain clouds remained high enough to reveal the runway a mile out.

While picking up fuel at FFM, the better options became evident. Offering ATC a heads-up before IGAKE that you might circle to 35 would’ve given everyone time to plan an alternative, including modified missed approach instructions. Delaying vectors for a longer circle back around to final might’ve bought you enough time to let the weather pass over the airport while avoiding unplanned maneuvering.

Even better, planning a weather escape with ATC a minute sooner would’ve allowed for a hold on the approach side of the airport, either present-position or at IGAKE’s HILPT as shown on the chart. Those actions would have reduced workload for both pilot and controller. While the second approach often proves better than the first, it’s still better to fly just one.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin, where her training specialties include pop quizzes on approach lighting systems, holding procedures, chart symbols and NOTAMs.