You’re flying along and want to talk to the controller. The controller is already talking to another aircraft, but you don’t hear that aircraft. You key up after diligently waiting a few seconds and then speak. Yet as soon as you unkey the controller is already talking back, but not to you. The controller is talking to someone completely different.

Eventually, the controller is done talking to the other aircraft that you can’t hear, a few seconds pass, and then the controller calls you. But you never heard the other aircraft respond, so how can you tell when to start talking?

How about that time you were talking to a particular facility and the next day at exactly the same location were on a different frequency to talk to that facility? Obviously in the moment, we follow instructions and aviate first. Later you are left wondering why radio protocol is changing on a daily basis, and how you can anticipate it next time to avoid any confusion. Long story short, you cannot. Wanna know why?

Radio Check?

Air traffic control sectors (airspace segments) and the frequencies assigned to them do not change on a daily basis, but the way they are configured due to traffic does. One day you might be talking to a controller on the only frequency the controller is working at the moment. Since you hear both sides of each conversation, it’s far easier to know when you can chime in if needed.

Another day, same drill, but the controller is talking to another airplane on another frequency, so you might hear “say again” more than once. ATC is often tasked to use multiple frequencies at once. It’s not the easiest thing to do with people talking on both, but we adapt and prioritize. One way we adapt to prioritizing is by the airplane’s speed. The faster they are going, the more likely it is that I need to get to them first before they enter another controller’s airspace without coordination.

Having an F-35 depart and need to climb will go before a Cessna on Flight Following mainly due to the distance traveled. ATC generally has the ability to combine and decombine positions on a workload-permitting basis. Meaning, entire sectors and frequencies can be split off at the push of a button. One sector of airspace is often broken into pieces when the traffic volume justifies it. Don’t worry, as long as you have already established contact with us, we will not forget you.

Perhaps you have heard “change to my frequency” before? This can happen when a controller has just combined up positions and is trying to keep everyone on one frequency instead of two or three. As you might suspect based only on your own observations, having everyone on the same frequency makes things much easier for both the controller and the pilots. Being able to hear what is going on helps pilots anticipate when they will have a turn to talk.

One question you might be asking by now is, “Are there any places where there are two or more frequencies permanently combined? Who do I call in those cases?” We’ll cover that just below, but the best thing to do is call who you intend to call, and if ATC wants you on a different frequency, they’ll tell you. Roll with it.

For example, you’ve probably been to an airport where the Ground controller is also working the Clearance Delivery frequency. That doesn’t mean you should call on Ground frequency for your clearance or flight following; use the correct frequency. Ground frequency is for movement; Clearance is for your IFR or VFR Flight following clearances.

If one controller is working them both, you might well be told to call on the other frequency. Do so. Then, if workload increases and the positions are split between two controllers instead of one, you will want to be on the correct frequency or you might get told to switch.

All that said, occasionally the functions are combined as noted on the ATIS: “Ground Control and Clearance Delivery are combined on 121.9.” Call the function you want, but on that one frequency.

Where Am I?

Okay, now that we’ve gone over broad frequency use, let’s talk about how those frequencies might be assigned. When I say “airspace,” you might be thinking Class A, B, C, D, etc. However, here, I’m talking about a particular volume of air that might, or might not, completely or partially correspond with those Classes of airspace.

For example, a busy airport might have multiple pieces of airspace that all exist within its Class C. On the other hand, that airport’s TRACON will be responsible for pieces of airspace that cover all of the Class B and beyond, but only up to a particular altitude. These pieces of airspace that a controller might be working are called sectors, and these sectors have lateral and vertical boundaries.

A controller responsible for a given sector (or, often, sectors) must know all the rules that apply to each including the boundaries, frequencies, any LOAs (letters of agreement) with neighboring sectors, and much more.

Sector boundaries are usually rigid, but multiple sectors can be combined and worked by a single controller as if they are one. Sectors are combined and then split frequently for weather, traffic volume, and ATC staffing.

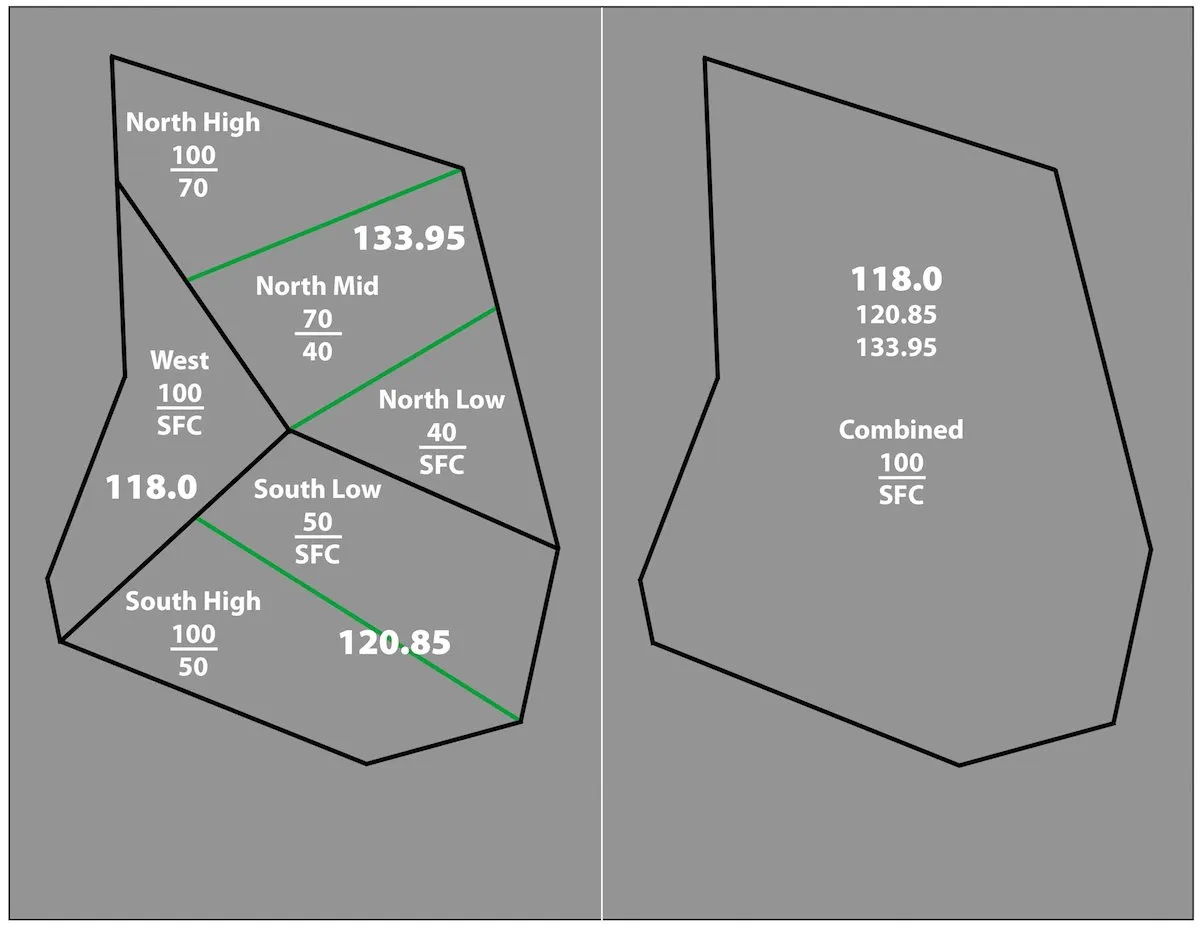

See the diagrams below. On the left you see black lines that depict three sectors: West on 118.0, North on 133.95, and South on 120.85. But the north and south sectors are also vertically divided by the green lines with three shelves of altitude (sectors) in the north and two in the south. When things are slow, all six of these sectors might be combined and worked by just one controller as you see on the right.

At no time is there more than one controller working different sectors on the same frequency, so each sector must have its own unique frequency if it is ever to be worked independently. It might be that the altitude stratification of the North and South sectors is for traffic or LOA differentiation, but they’re never worked independently, so all altitudes in the sector are worked by one controller on one frequency, as shown.

If sectors are de-combined or operating separately, controllers will use the frequency specific to each sector. When sectors are combined, a single controller will use a specific “combined” frequency as determined in their standard operating procedure, or the one with best coverage, such as 118.0, which is shown bigger on the diagram.

Say you travel across this airspace on the same route, at the same altitude, at the same time, three nights in a row. You get a different frequency every single night. There are a few reasons this could happen: controller preference, specific intent of each in an LOA or SOP within a facility, or it could just be that a radio is broken. Be sure to check your NOTAMs and, of course, your chart supplements in case you call your “usual” frequency and there is no response.

ATC might or might not be able to hear you or transmit in response. It’s rare, but frequency reorganization does occasionally happen. So, just try a different frequency. If all else fails, try your previous frequency, or if very urgent, the emergency frequency, 121.5.

Towers and centers sometimes combine and decombine similar to this, but obviously on a different scale. Class D towers have a lot less airspace than centers. If you encounter something similar to this within a tower environment, it could be that it is the same tower, but it is split to allow operations on different runways. Some towers have a north and south controller (generally those with east/west runways) and some have east/west controllers (north/south runway).

With this understanding, if these scenarios become apparent to you, be extra vigilant looking for other airplanes. In an east/west split of the same Class D environment, the two controllers are generally standing close to each other, but they can each be quite busy. Internal communication hiccups are rare, but do happen. Keep an eye out.

VHF vs. UHF

While most military aircraft today also have radios that operate on the same VHF frequencies we used, military communications still heavily, even preferentially, operate on the completely incompatible UHF frequencies. Most air traffic facilities have both capabilities, but of course civilian aircraft only operate on VHF. Thus, you might hear a controller simultaneously transmitting on VHF while working and talking to military aircraft on UHF. Of course, you’ll only hear the VHF side, or, if the controller switches entirely, neither.

If you are flying near a military base, there is a good chance you won’t hear the military pilots talking to ATC. In this case, controllers could be working a single sector, but have two frequencies—one VHF and one UHF—assigned to that one sector.

A radar controller combining more than one sector, each having its own VHF and UHF frequency, is common. Then at the end of the day, the radar facilities that are not open all night give those frequencies to center. So, our six-sector/one-sector drawing could even represent a TRACON during the day and the overlying center at night. Your take away is to try to keep the big picture in mind.

“Change to my frequency…”

Okay, now we’re back to one of our original scenarios. The simple, “Change to my frequency” instruction—meaning the same controller wants to talk with you on a different frequency—can happen for three reasons. First, the controller is working multiple sectors and there’s no one frequency covering them all, so you’ve got to change to the next frequency. Or, it might be that the sectors were combined after you were in one and the controller wants to consolidate traffic on the same frequency. Last, it could simply be one of the steps in splitting up sectors that were previously combined.

How do you respond? Per the AIM 4-2-3.d.1, all frequency changes should be acknowledged but this scenario is not clearly addressed and the next paragraph does say that the initial call can be abbreviated.

Your acknowledgement on the old frequency might be as simple as, “Switching. Cloudhopper 45 Juliet.” However, it’s common practice to skip the acknowledgement if you can quickly dial in the newly assigned frequency without an undue delay while the controller waits. Either way, your report on the new frequency is simple: “Cloudhopper 45 Juliet on 123.45.”

A good pilot is always learning and adapting to the circumstances. Pilots and controllers both are often met by unusual situations and must quickly identify and adapt to the new requirements. A pilot might not be expecting several frequency changes in a few minutes, and the controller working might not expect their sector to be combined out of nowhere, yet it happens.

I’ve personally gone from no traffic to 10 aircraft in a couple minutes. Some days you have one controller for 100 miles, and then the next day have four in the same 100 miles. The best thing pilots can do during these times is just understand that internal ATC changes are happening and to fly right through them.

There is just the normal ebb and flow of the airspace, and sometimes it’s not even our call to combine or decombine the sectors. Just like you, we fly through it. And, as always, if you have questions, just ask.

Sector Musical Chairs

I work TRACON at an airport with multiple runways. With busier traffic we normally will “decombine” in an east/west sector setup. One day I was working multiple airplanes on one frequency when the training team arrived, wanting to do some training on one of the sectors I’d combined. So, I kept one sector while I briefed the new controller/trainee to take the other.

Obviously, airplanes don’t stop during a position briefing, so I had to keep working my traffic while briefing. At the end of the brief, the controller assumed the position for the opposite side, and I started to switch all airplanes on that side to his frequency. But just a few minutes after this brief took place, I had nothing to do on my side. I just sat there and watched the trainee work his side of the moving puzzle, and being he was brand new to ATC, he was “getting worked.” Minus the fact that he got really nervous, he pushed through it and moments later, all the airplanes and helicopters went to land.

After the last airplane was on its base leg to land, the Controller in Charge (CIC) decided to recombine the positions. So, we got out our checklists, scanned the area, and briefed. He gave me back the position sweating bullets and since there was nothing else going on, “I have the position” came out right away. Gaining control of the whole Class D, I nodded to his trainer and told him that the newbie did well. They went downstairs and there I sat with no traffic. This all happened in about 25 minutes.

Sure enough, then several of the flight school airplanes started coming back all at once. We did the same thing all over again (before it got busy this time) and he seemed to handle it better. Controllers are often asked to “jump in” during busy times and unofficially “get the picture” so that when briefing time came, they can assume it quickly. Sometimes we are even asked to remain in the control environment as a “stand-by” in case workload spikes. When I first arrived at my facility, I was not a big fan of the practice—mostly because it was new—however after several months of training with the mindset of having to jump in quickly, I’ve adapted to it and see that it works quite well. —EH

Elim Hawkins combines and decombines frequencies so readily that he occasionally finds himself wanting to listen to two radio stations at the same time during his drive to work.