I always enjoy the magazine. Thank you to all who provide and produce the content.

In Tarrance Kramer’s “Towerless Tribulations” article in April, he discussed the benefit of pilots cancelling IFR before landing at a non-towered airport. I agree with this sentiment; however it is worth noting that there are commercial operators whose Operations Manuals prohibit them from cancelling IFR until after landing and also prohibit departing VFR and picking up the clearance in the air. I worked at such an operation for many years and was aware that keeping my IFR clearance until landing wasn’t the most efficient operation or the best way to make friends. Nonetheless, I was required to do just that.

There’s something that would expedite the process for all: a pilot who intends to cancel IFR in the air should just cancel when getting the field in sight, instead of waiting for the controller to first clear them for the visual approach. “N12345 cleared for the visual approach to the XYZ airport. Radar service terminated. Report your down time here or through or Flight Service. Frequency change approved.” are all part of an ATC transmission that could be eliminated by just being proactive. We should all work to minimize our radio verbiage.

J. Chris Lemon

Evansville, Indiana

You make a good point that is easy to overlook that some commercial operators are prohibited from cancelling in the air.

You also echo the reader comments we published a few months back about cancelling before the controller recites the “cancel mantra.” This is worth repeating. It’s common for ATC to point out the airport and ask the pilot to report it in sight. The pilot then reports the airport in sight, followed by the controller reciting the “cancel mantra.” Only then does the pilot cancel. It’s ever so much better if the pilot cancels upon seeing the airport.

However, we hasten to point out that getting an airport or runway in sight doesn’t guarantee you’re in VMC. Before cancelling IFR, be sure you know your airspace type and that you’re in VFR weather for that airspace. This is the other side of the coin where a pilot, trying to cancel early to be a good citizen, could end up in trouble for not having the requisite VFR weather for the current airspace.

Prevent Misfueling

I’d like to share my experiences and revised procedures relative to your June “Fuel Blunders” article. I’ve personally experienced two misfueling incidents. Fortunately, I caught both of them while still on the ramp.

The first was in a Cessna 421—a piston-engine twin. A relatively new line person assumed it was a turbine aircraft and fueled it with Jet-A. In that case I walked out to the airplane just as he was finishing and I noticed the markings on the fuel truck. Of course, he was mortified when I pointed out his mistake, as was the FBO manager. Since no tank had been empty and the engines hadn’t been run, I was comfortable just draining, rinsing, and refilling the tanks (with avgas).

The second was in a King Air I was flying Part 135. It was fueled with avgas. I was sitting right seat that day and we were running a bit behind. So, I was finishing up some paperwork as the left seater started the engines. As I was putting the fuel receipt away, the “100LL” caught my eye, and I shouted, “Shut ‘em down! Shut down the engines,” which he did without hesitation. The engines had only been run less than a minute, so it was unlikely gasoline made it into the hot section.

That incident cost us an unexpected overnight and some unhappy passengers. We went straight to the FBO manager to explain. He verified it wasn’t just a paperwork error. Then, the aircraft was towed into the hangar where they disassembled the entire fuel system on each engine and thoroughly flushed it out with Jet-A, in addition to draining and flushing the tanks and lines.

After that second incident, I made it my personal procedure that I’d try to be present for the fueling every time. If that was impractical, I would at least observe which truck went to the aircraft and then I’d carefully review the fuel receipt for type and quantity.

Thanks for your great, informative magazine.

Sal Cruz

Watsonville, California

Related to the June article about Fuel Blunders, when I had my Turbo Arrow III repainted, we put “Arrow III” and left off “Turbo.” That was our caution for any line person filling with Jet-A thinking it had a turbine engine.

Bruce Bream

Cleveland, Ohio

While the chances of a line person misfueling an Arrow as a turbine are probably slim, they’re not zero. You were thinking proactively and out of the box to prevent fueling accidents. Good choice.

Accident or Incident?

Your NTSB quiz in August raised an issue for me. I had a nosegear failure on takeoff in April and the NTSB’s determination of accident versus incident is a little more nuanced than question 2 would make it seem. The NTSB wanted to see photos of the damage and when they saw that the motor mount had been significantly damaged they determined it was an accident rather than an incident.

Your NTSB quiz in August raised an issue for me. I had a nosegear failure on takeoff in April and the NTSB’s determination of accident versus incident is a little more nuanced than question 2 would make it seem. The NTSB wanted to see photos of the damage and when they saw that the motor mount had been significantly damaged they determined it was an accident rather than an incident.

Iain Clark

San Jose, California

The NTSB determination isn’t surprising. If it had been only a gear collapse, it was an incident. But, in the process the aircraft received structural damage (motor mount) which is clearly an “accident.”

Better to Hear You With

I’d like to add to the comments on the discussion of “Incommunicado” in the June 2023 issue.

A noise-canceling headset with Bluetooth is nearly mandatory for effective communication inside an airplane with the engine running, either on the ground or in the air. I consider this kind of headset to be a no-go safety item.

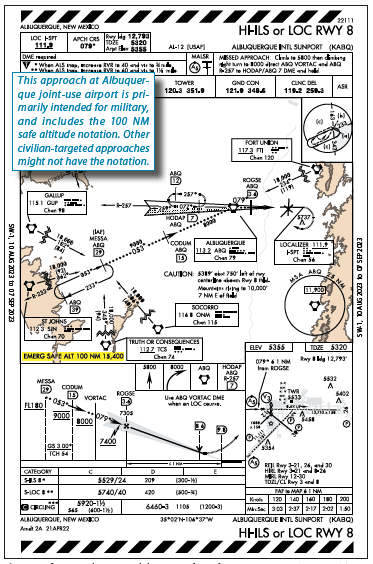

Military and Joint Use (military/civilian) airports have MSAs or TAAs but also an EMERG SAFE ALT 100 NM XXX FT, which covers considerable real estate compared to the meager 25 NM for MSAs and 30 NM for TAAs. I’d like to see all approach charts changed to include a 100 NM radius safe altitude.

Luca Bencini-Tibo

Weston, Florida