Your home airport’s winds almost always favor Runway 30 departures via a left-turn taxi at Alpha. Today, the wind favors Runway 12. Reaching Alpha, which way should you turn? If you turned left or were so tempted, you fell into or narrowly avoided the expectation bias trap.

Expectation bias lurks in everything we do, especially things we do repetitively. When we get in a car, we expect it to start. When we turn on the tap labeled H, we expect hot water. Each time you taxi to Runway 30, expectation bias is strengthened. No wonder it so quickly becomes automatic.

The NTSB has cited expectation bias as “a psychological concept associated with perception and decision-making that can allow a mistaken assessment to persist.” Expectation bias, and its cousin, confirmation bias, can cause a person’s incorrect belief to persist despite evidence to the contrary. Expectation bias comes from what we expect to see or hear rather than what is actually seen and heard.

These biases are so strong that Harrison Ford landed on a taxiway because he saw what he expected to see—a runway, even though a taxiway and a runway look different. In an identical fashion, an Airbus A320 lined up with an occupied taxiway at KSFO in night VMC. Expectation bias occurs unconsciously and, because we believe it, is nearly impossible to overcome once established.

Expectation bias has caused many accidents and incidents, especially at night in VMC, where fewer clues are available to aid airport and runway identification. One reason is that the pilot identifies the wrong airport visually and then, perhaps because they are utterly convinced, fails to use instruments to verify the airport and runway. Not surprisingly, expectation bias is among the most common causes of runway incursions involving pilot deviations.

Other runways, taxiways, and nearby highways can lay the foundation for expectation bias. To help avoid misalignments, the FAA publishes Arrival Alert Notices in the Special Notices Section 3 of the Chart Supplement. It is also covered in the Airport Remarks section as “Note: See Special Notices – Arrival Alert.”

ATC Biases

How many of us uncritically accept instructions from ATC? Most instrument pilots have a sense of what to expect next. Situationally-aware pilots compare it to what ATC issues and act accordingly or query the controller. In one case, in the author’s experience, ATC issued a heading away from the desired localizer. Immediately ringing a bell, we inquired. It turned out that ATC was vectoring us to the wrong airport and approach.

Expectation bias can fool us in other ways. If you expect the BONGO 3 Arrival as usual, you may load that arrival despite being assigned another one by ATC.

Mitigate Expectation Bias

Expectation bias can garble a verbal transmission from ATC if you have a preconceived notion of what they will say. Defeat that tendency by listening and repeating to yourself exactly what you heard. Then, comply unless something doesn’t make sense.

More broadly, the best way to overcome expectation bias is through self-training that stresses questioning observations we see and hear. If everyone is departing on Runway 12, are you aware of that? If you see a runway sign or marking that says RWY 12, does that register? We should always seek cues that confirm or conflict with our actions. Have your head thoroughly in the game.

Aircraft crews rely on the challenge-response system. One pilot sets the flaps, and the other ensures the setting is as stated. In principle, this reduces the prospect of expectation bias.

Since most of us don’t have a spare pilot, touch everything you set. These two steps help defeat the natural tendency of the brain to see what it is used to seeing rather than what is set, and it keeps you from rushing. Remember that slow is smooth, and smooth is fast.

Confirmation Bias

Once we form a mental model, we naturally seek cues that support the desired action. We may exercise selective recall by accepting only data that conforms to the mental model and discount, ignore, or otherwise reject information contrary to the model. To do so is to override an error-detection mechanism, and confirmed expectations reduce the sensitivity of the mechanism even further.

Confirmation bias can strongly distort a mental model to the point that it’s almost impossible to let go, even when confronted with contradictory information. It’s too late once your taxi clearance no longer matches the signage.

Mitigate Confirmation Bias

Avoid making assumptions based on limited information and solely on emotions. Be willing to change your mind if warranted by the evidence. If you miss a turn on a taxiway, recompute your way to the runway if there is no tower or ask Ground Control for new directions.

The discomfort you feel when something is wrong is called cognitive dissonance, which means that our minds simultaneously have two contradictory beliefs, values, or ideas. Dissonance can be a warning mechanism and should not be ignored. It is resolved by changing our behavior, such as finding another way to the runway or seeking confirmation that the airport and runway are correctly identified.

Neither expectation nor confirmation bias is mental laziness. Biases are simply a part of the way our brains process information. Psychologists have identified 130 to 150 cognitive biases that we all carry. The good news is that we can learn to recognize and prevent them once we realize they exist.

Normalization of Deviance

We know that ice on the wings is bad. But how bad is bad? The FAA’s opinion seems to be, “There is some and none, and some is too much.” Let’s say you fly somewhere and pick up some light rime ice. The airplane flies fine. You make a mental note: a little light rime is okay. You have just normalized a deviance. The next time, you pick up a little more, and the airplane still flies fine until one day, it doesn’t, and you lose control of the airplane.

In her 1996 book, The Challenger Launch Decision, Dr. Diane Vaughan defined normalization of deviance as “the gradual process through which unacceptable practices or standards become acceptable.” Such practices are contagious. They can spread throughout an organization, infecting current and new employees. Should someone object, the usual retort is, “We’ve always done it that way.”

Some Examples

Unstabilized approaches become the norm. The new vibration in your aircraft becomes the “new normal” until your mechanic discovers a failing magneto. Perhaps you don’t bother to check that the GPS database is current. One day, something goes badly wrong. Too late, we come to our senses, realizing how serious these deviations are.

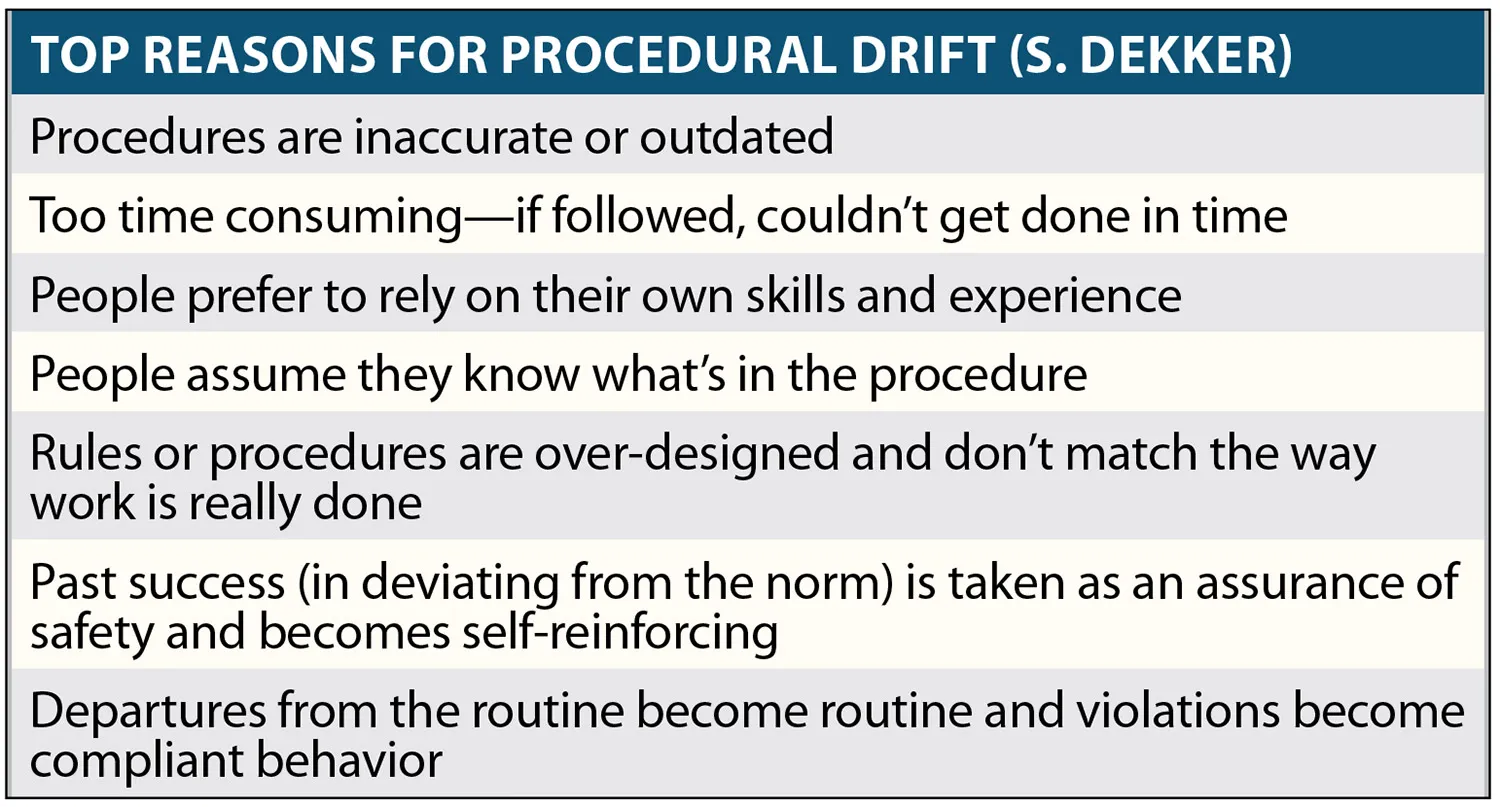

Procedural Drift

Given the regs, AIM, checklists, and the POH, there is a tendency to drift away from those procedures over time.

Performing a checklist from memory is one example. What’s the point of a checklist if it falls out of use? For each procedure you use, ask yourself, “Am I letting myself drift?”

You can easily recognize drift because it’s the difference between “work as imagined” and “work actually done,” according to Dr. Stian Antonsen, a noted safety culture researcher.

Let’s suppose you take a thorough Instrument Proficiency Check. You refresh on profiles to fly, standard operating procedures, systems knowledge, and emergencies. You raise your procedural efficiency to each designated norm. Yet, over time, actual performance typically drifts below your new baseline.

The ICAO suggests that procedures learned cannot always be executed in real-life flying. For example, we don’t hold very often, so properly flying a hold can be difficult. Sometimes, procedures look good on paper and work in principle but not in practice. People naturally diverge from baseline to the extent needed to achieve a desired outcome.

ICAO recognizes that all organizations (and individuals) contain a degree of drift, which is why we have recurrent training. At best, the drift strays from baseline and then varies around a point close to ideal. In the worst-case scenario, deviations can begin slowly, almost invisibly, then accelerate toward the line between safe and unsafe operation. Procedural noncompliance feeds on itself and increases the likelihood of subsequent errors.

Even capable, highly experienced pilots can devolve into complacency. Paradoxically, acknowledged experts carry extra risk because they can come to believe that their knowledge gives them license to deviate.

To fly our best, let’s be humble and respect the medium in which we operate. In the words of Wilbur Wright, “In flying, I have learned that carelessness and overconfidence are usually far more dangerous than deliberately accepted risks.” Good stuff, that.

The Human Factor

The FAA understands all the above very well. It’s why they’re so sticky about adherence to regulations. They know they cannot let up even a bit, lest pilots begin sliding down slippery slopes.

Not long ago, pilots near a local airport began cutting through a small corner of Class D airspace without contacting the tower. The practice became normalized and then rampant until the FAA started violating delinquent pilots.

Lean In

Each time you fly, press yourself to do a little better. Minimize expectation bias by questioning what you see and hear. Eliminate confirmation bias by listening to that little voice that says all is not right. Post-flight, replay the flight in your mind, but be fair to yourself. You did a lot right, and a few things need work. Over time, you’ll become the pilot everyone wants to be.

Fred Simonds, CFII, strongly believes in the power of systematic self-improvement.