Beyond separating and sequencing aircraft, air traffic controllers are responsible for managing expectations. When I’m working traffic, I must ensure that what each pilot expects to be doing matches with what I expect him to be doing. Otherwise, it’s like trying to act out a play when all the actors are reading from different scripts.

That’s where the readback/hear back loop enters. By actively listening to pilot’s responses to clearances and catching incorrect readbacks, controllers prevent potential errors before they occur. One undetected bad readback is often the thing that turns a safe operation into a frightening situation.

Staying in Sync

Imagine I tell you, “Descend and maintain 4000.” You reply, “Descend and maintain 3000.” I miss the incorrect response and expect you to level at 4000.

Thinking you’ve been assigned 3000, you descend into another aircraft already at that altitude, resulting in a dangerous conflict. That’s on me, for missing the readback. Why me, and not you? The rules say so.

The ATC rulebook, FAA Order 7110.65, says this under 2-4-3 Pilot Acknowledgment/Readback: “Ensure pilots acknowledge all Air Traffic Clearances and ATC Instructions. When a pilot reads back an Air Traffic Clearance or ATC Instruction: a. Ensure that items read back are correct.”

In AIM 4−4−7, “Pilot Responsibility upon Clearance,” it says, “Pilots of airborne aircraft should read back those parts of ATC clearances and instructions containing altitude assignments, vectors, or runway assignments as a means of mutual verification. The readback of the ‘numbers’ serves as a double check between pilots and controllers and reduces the kinds of communications errors that occur when a number is either ‘misheard’ or is incorrect.”

Let’s note one grand distinction: The pilot’s responsibility is listed in the AIM, which is more of a “best practices” document, as opposed to regulatory. It says a pilot “should readback….” FAA Order 7110.65 is a regulatory document and doesn’t leave room for ambiguity. ATC must—not should—ensure all readbacks are correct. We are supposed to fix any problems.

Which Way Ya Headed?

So, what could be the result of a mistaken readback? We’ve already mentioned altitude. What about routing?

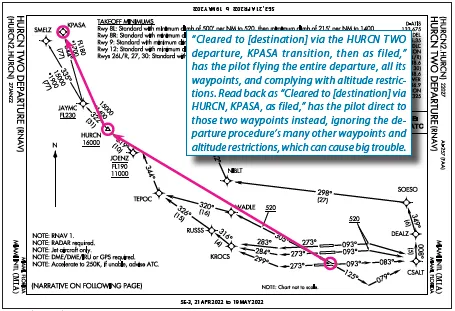

Imagine an airline pilot at Miami International Airport (KMIA) calls for their clearance. Clearance Delivery issues them, “Cleared to [destination] via the HURCN TWO departure, KPASA transition, then as filed.” The pilot reads back, “Cleared to [destination] HURCN, KPASA, as filed.”

That readback should be raising some red flags. The “TWO” in the HURCN TWO Standard Instrument Departure (SID) is missing, of course, and he left off the word “transition” after KPASA. If we go by his readback alone, his cleared route goes direct from the airport to HURCN—the waypoint itself—then direct to KPASA. To him, the SID doesn’t exist. Per his readback alone, he won’t overfly the numerous fixes between the airport, HURCN, and KPASA, or comply with any of the SID’s altitude restrictions.

It’s Clearance’s responsibility to correct him, per the 7110.65. Also, all ATC communications are recorded. If that aircraft takes off and goes direct HURCN, instead of flying the HURCN TWO departure, and its unexpected maneuvers puts him in conflict with another aircraft or airspace, the investigation will place blame on Clearance for not fixing it before the airplane left the ground.

So, the Clearance Delivery controller corrects him, with some extra emphasis. “Verify routing, cleared to [destination] via the HURCN TWO departure, KPASA transition, then as filed.” It’s at this point I wish everyone would check their ego. Yes, I know we’re talking about aviators and ATCs here. I’ve seen some pilots pull a Captain Snappy when a controller calmly corrects them, taking it personally when it’s just part of our job. Certain controllers could be more patient too, with a pilot that could be on his umpteenth short-haul flight of the day.

If you’re a new pilot in training, working on your instrument rating, perhaps after you’re reading this, you’re thinking, “The pilot was probably going to fly the HURCN TWO and KPASA transition anyway, right?” Ask yourself: can you listen to that readback above and say, with absolute certainty, that he will fly his assigned route? You can’t.

I’ve seen too many unexpected situations to take that chance. Airliners veering off SIDs, directly into traffic … runway incursions by military fighters told to hold short … corporate jets descending below their assigned altitudes, into antennas … and those were with good readbacks. Why tempt fate by breaking yet another link in the safety chain by letting a bad readback slide?

In the aftermath of those moments, I’ve agonized, “Did I tell them the right thing? Did they read it back correctly?” Experiencing that sinking feeling motivates me to ensure my clearances and readbacks are correct going forward.

You Lookin’ for Me?

Of course, a good readback doesn’t matter if the wrong plane is reading it back. Many aircraft and air carriers have similar sounding callsigns. Combine that with the often rapid-fire rate of ATC instructions, and there’s a chance an aircraft other than the one intended might take a clearance instead.

Under “EMPHASIS FOR CLARITY” 2−4−15 ATC Order 7110.65 says, “Emphasize appropriate digits, letters, or similar sounding words to aid in distinguishing between similar sounding aircraft identifications. Additionally: a. Notify each pilot concerned when communicating with aircraft having similar sounding identifications.”

In practice, each aircraft will be told, “N12345, use caution, similar-sounding callsign on frequency, N21345.” If there are two air carriers from two different companies, we double-up their company name. “United 435 United, use caution, similar-sounding callsign on frequency, Delta 435. United 435 United, descend and maintain six thousand.”

So, what happens if someone takes a clearance meant for someone else? It’s a potential snowball effect of confusion and calamity.

A few years ago, I was in our tower and had Airbus A320 number one waiting at the hold-short line of a runway. A Citation X was on final. Working all positions combined, I was pretty busy. In the midst of it, I taxied out a second A320, who I needed to cross to the other side of the runway. I told him, “[Airline] 3251, cross runway niner at Hotel.”

Suddenly, my headset erupted with the squeal of two transmissions blanking each other out. In the mess, I heard the [Airline] name twice. That’s when I realized: the callsign for the first Airbus was 3351, nearly identical to his company aircraft’s 3251. Both had readback the runway crossing clearance. Immediately, I said, “[Airline] 3351, hold position.” I told his company the same.

Now, it was time to assess the damage. I could clearly see [Airline] 3251 was nowhere near the runway yet, so he was fine. However, Airbus #1 was a mile away from me, and hard to see details. “[Airline] 3351, are you across the hold-short line?” “Yes, we are,” came the reply. Argh. The runway was fouled. I looked at the Citation closing on final. There was no time for [Airline] 3351 to taxi off the runway, so I did the only thing I could: I told the Citation X to go around.

Obviously, I should have clarified that there were two similar callsigns on frequency. I simply hadn’t realized it at the time and fully own the oversight. That said, this incident also serves as a reminder: if ATC issues you an instruction that doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, question it. For instance, if you’re first for departure, why would ATC suddenly have you cross the runway? If the pilot of [Airline] 3351 had said, “Verify that crossing call was for [Airline] 3351?” it would’ve saved a lot of heartache.

What if airlines schedule similar-sounding flight numbers for the same time of day, every day? ATC is supposed to report it, per 2-4-15: “b. Notify the operations supervisor−in-charge of any duplicate flight identification numbers or phonetically similar-sounding call signs when the aircraft are operating simultaneously within the same sector.” I filed some paperwork after that incident above, hoping to reduce future potential for confusion and workload increase.

Stamping it Down

How do controllers mitigate the bad readback threat? First, we try to keep as many planes on the same frequency as possible. If a controller has different frequencies, the aircraft on those different frequencies can’t hear each other. As one is reading back a clearance, another could be checking in, and a third might report a PIREP, not knowing they’re all stepping on each other.

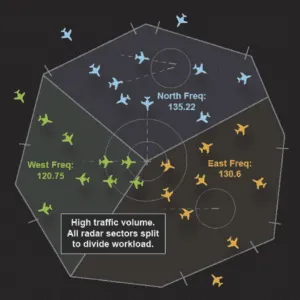

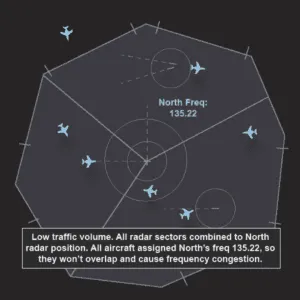

Therefore, a proactive controller assigns all the aircraft the same frequency. Usually, ATC radar facilities have a “mother” sector to which all other sectors combine when traffic is slow. During the day, a facility might have North, East, and West sectors open, each with its own frequency and controller. Early in the morning or late at night, perhaps those all combine to the North sector, worked by a single controller.

Take note: If you fly out of an airport late at night or early in the morning, it’s far more likely you’ll be assigned a different frequency than one shown on a chart. That’s typically the “mother” sector. Also, if an ATIS says Ground or Clearance Delivery is combined on a certain frequency, use that frequency.

We also try reducing internal noise pollution. Control towers and radar rooms can already be loud places, with controllers speaking fast and furiously during busy periods. A controller could be intently listening to your readback when the person beside them yells across the room, “Hey, I need an altitude amendment on this airplane!” and drowned you out. Or maybe another facility called on a landline, blasting out the speaker above his head. A high percentage of “say again” ATC requests simply stem from normal operations.

Distractions can also come from sidebar conversations, like two friends catching up their weekend adventures, or the animated group venting about their Dungeons and Dragons for Sports Fans results (aka fantasy football). Therefore, controllers and other personnel on break are encouraged to keep it way down or leave the operating area. The traffic and the operation must come first.

Additional radio techniques allow readback management as well. I often use, “Standby on the readback.” Imagine I’m working tower. I’ve just cleared an airplane for takeoff. Another calls for a long, full-route IFR clearance. I have a moment, so I issue the full-route clearance, and end with, “Standby on the readback.” I then tell the departing aircraft: “Contact departure.” Just then, two aircraft call for taxi. I taxi them out to the runway.

Afterwards, I return to the original full-route aircraft: “Go ahead with your readback.” It’s all priority of duty. I resolved the moving traffic first, and then asked for the readback once the frequency was clean. If I hadn’t done that, I would’ve been late switching my departure, and his readback could’ve been stepped on by the two aircraft requesting taxi.

These good readbacks are vital to your safety, safety of the entire system, and our peace of mind. If you ever have a question on an instruction, don’t hesitate to clarify with ATC. We all need to be speaking the same language, and understanding the expectations.

July 2022