Ahh, February in South Carolina. While not the warmest refuge from a northern winter, it’s usually above freezing. That means hoodie weather for those who like their mornings cool and crisp. A good day for a dual-mission trip—you’re headed to Greenville for a mid-winter convention, and in the right seat is your CFII, who is looking forward to a long-overdue recurrency session with you. Naturally, he wants to see how you hand-fly approaches in IMC before parking your speedy two-seater for a two-day stay. But of course there’ll be lots of curveballs tossed in—some planned, some not.

Lesson One

Fortunately, clear skies prevail from Hagerstown, Maryland, to the fuel stop in Roanoke, Virginia, so potential icing conditions during the first half of the route aren’t a consideration. It does get cloudy en route to Spartanburg Downtown Memorial (KSPA) on the east side of Greenville.

No matter that you filed Shelby-Cleveland County (KEHO) as the official alternate. That met the criteria for weather (better than 800-2 for RNAV approaches) and fuel (you can land with 45 minutes of cruise reserves). Unofficially, you plan to fly approaches to KSPA followed by two west-side satellite airports, Donaldson Field (KGYH) and Greenville Downtown (KGMU), the final destination.

Great—there are LPV minimums for all the airports, starting with the RNAV to Runway 5 at KSPA. However, your ever-devious instructor has other ideas, and figured out that all the runways you will use have ILS approaches. Better study up en route. For the ILS 5 at Spartanburg Downtown, DME is required, and you can substitute the GPS navigator. That requirement is for the lone initial approach fix, FREST, the FAF at VETPY, and the localizer-only stepdowns, which you should also review just in case.

You got quizzed on that Locator Outer Marker, JUDKY, which is situated off the 276-degree radial from the final fix and seems to be extraneous for this approach, and it is (for now). Your instructions are to arrive from the north via the SPA navaid’s transition and fly the IAP as published to include, of course, the hold-in-lieu-of-procedure turn.

On the way to FREST, you figure if you see the runway and landing is assured by the time you reach the Visual Descent Point one mile out, you can fly visually the rest of the way. Take a quick break and file to the next stop. That’s not what happens, though. Reported weather is often an hour old, and so the vis was poorer than expected. You clung to the glideslope and flew past the VDP to the 1002-foot DA, saw the PAPI, but would not dare continue. The missed approach began right there. Where were the lead-in lights? Turns out the RAI (Runway Alignment Indicator) lights were temporarily out of service (Did he plan that?) At any rate, you got caught unaware. First lesson learned: Check NOTAMs.

First Alternate

The missed approach, memorized on the way to Spartanburg, wasn’t needed as an immediate vector came across the radio along with a climb to 3000 feet. You requested a deviation to Greenville Donaldson Field. At KGYH, another ILS is available, of course (that was planned). Again, check the equipment box: DME or radar, check. Briefing strip: “DME required when GSP App Con closed.” Okay, so that’s a reason for the DME-or-radar requirement.

What if you didn’t have DME or an accepted substitute, or your CFII asks, “What are the operating hours for Greer Approach?” It’s in the Chart Supplement, which took a five-minute hunt-and-tap while your right-seater played autopilot. He had a good laugh over that one. Next lesson learned: Know where to find stuff that isn’t on the charts, like ATC and tower hours.

At least he didn’t have you fly another HILPT and you got to start the approach from DEANS, which was a bit far to the south but noted “NoPT.” Notice also that JUDKY is an NDB on this plan view. While also not part of this approach, it appears to be lined up with Runway 23.

But there’s just an RNAV approach to the other end. Perhaps there used to be a ground-based hold or approach to that runway using JUDKY, and it still serves as the reference fix for the Minimum Safe Altitude of 3000 feet for 25 miles around.

This time, you remembered to pull up the NOTAMs, albeit a bit late as you’re already on approach vectors. There is one; darn if the runway’s hook-cable arresting system is out of service. That woulda been fun. Anyway, the weather was a little above the 1156-½ minimums, which allowed for a full stop landing after breaking out at 1200 feet.

But you lost points since you neglected to call out altitudes as you descended to minimums, and even forgot to brief the missed approach while on vectors. Even though you likely won’t need those instructions, busy airspace or a loss of comms could require you to use ’em. Lesson three: Brief thoroughly. Get delay vectors if you have to. And 3.1: Monitor your final path, cross-check every hundred feet, and assume a missed until landing is assured—you know, with a normal, stable approach that should not so much as raise an instructor’s eyebrow.

No Shortcuts

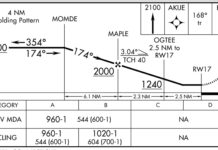

Now, with a local IFR clearance, you’re off to the ILS 1 at Greenville Downtown to the north. Because it’s so close to Donaldson, you’re on vectors out to the southwest. With the latest report there at 300-2, you wonder about this approach’s distinguishing characteristics. For starters, now ADF is required equipment. And: “RADAR required or procedure entry at SPRKI.” The ADF requirement is for, it just so happens, JUDKY. Here, it has multiple roles as a Locator Outer Marker/FAF/IAF. In another act of mercy, your instructor won’t have you flying a procedure turn from JUDKY, so vectors to final will suffice.

But notice two things: The localizer FAF is 3.6 NM from the runway, a little closer than usual. Also, you’d better be ready to intercept the glideslope before that point; it’s further out than the localizer FAF but probably gives you the five-ish miles you are accustomed to for the final approach segment.

The glideslope, by the way, is labeled “unusable below 1216.” Before you wonder about whether that affects the DA, that is the DA. But now closing in at 1400 feet, you’ve let the aircraft get one dot below the glideslope. Is there time to correct? Your coach waits for the answer. By the time you do decide to go missed, the altimeter’s passing through 1240—better a bit early than a bit late. ATC again is gracious with an easy altitude and heading, but requests your intentions.

Is a second approach justified, or do you look for better conditions? Weather check: 300-1. Since you should be able to fly the ILS to landing if you lock in on the glideslope to 1216 feet, you request a second approach. That one goes much better, and you even break out at 1250 feet. Lesson four: Plan intentions ahead of time based on weather, your own performance and flight conditions, such as fuel; don’t wait to be asked.

Now you get to log four approaches, a hold, and gobs of actual instrument time. Your instructor didn’t plan on all of that, but got his objectives done. You also collected several takeaways on treating every approach with fresh eyes while using their common threads to fly those procedures as, well, as precisely as you can.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. She spends the long winter there concocting multi-leg flights to keep herself (and unsuspecting clients) prepared for spring instrument weather.