Many consider the instrument rating as the most difficult aeronautical achievement. This is probably even more the case today than when I earned that coveted capability almost a half-century ago. While aircraft haven’t changed much, the avionics, regulations, and AIM have all undergone significant metamorphosis.

Today’s GPS equipment and the procedural techniques required in Technically Advanced Aircraft (TAA) require even greater levels of proficiency. Programming the avionics demands a familiarity with button-pushing that can easily confuse a pilot who’s not intimately familiar with the systems.

Professional pilots undergo rigorous initial and recurrent training, then stay proficient flying up to 1000 hours a year. But, we casual pilots must find other ways to regain and retain these skills. Too often, when competence deteriorates, bringing it back to an effective level can require a more structured approach than the typical Instrument Proficiency Check (IPC) tasks. These are listed in the Instrument Rating— Airman Certification Standards (ACS) FAA-S-ACS-8B Appendix 5.

A combination of the academic and the practical must be integrated with frequent opportunities to work the avionics— preferably within the system— to fully appreciate the interrelationship that must exist to fly safely and competently. It’s important to move the application level of learning to correlate with previous and subsequent information.

Concerning the academic, there are excellent programmed learning curricula available from Sporty’s, Gleim, King, and others. Staying up to date requires frequent interaction with the subject matter.

Demonstrating Competency

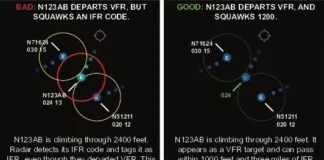

An IPC is only required if the pilot doesn’t log (in six months), the rather simplistic tasks stated in §61.57—and remains out of currency for an additional six months. The maneuvers that must be recorded include six approaches, holding procedures, and intercepting and tracking courses through the electronic nav systems.

So, you can be legally current without exploring many complexities of today’s airspace. It is especially true when flying a TAA with a glass Primary Flight Display (PFD) and Multi-Function Display (MFD). Not challenging enough? Add some automation.

I wouldn’t discourage a pilot from working on his/her own to improve proficiency, but it can be a daunting task. Your proficiency is only as comprehensive as the training. If you’re rusty, consider designing a thorough session—or two— with a CFII.

Instrument instructors are a pivotal part of a meaningful curriculum. Sure, they’ll cover the basics of §61.57, but there’s room for a lot more: regulations, AIM, flight planning and clearances, weather, and applying sound judgment. Add emergency procedures, risk assessment, and aeronautical decision-making scenarios in the single-pilot environment, and your IPC becomes a formidable undertaking.

The Environment

We commonly say, “The cockpit is a terrible place to learn.” It’s noisy and presents many distractions to interfere with the educational process. Thus, simulators have become indispensable.

At an even more basic level are the avionics trainers available for personal computers. These allow exercising most features of the EFIS, enabling you to focus on the so-called buttonology.

Garmin’s G1000 has an excellent trainer. However, it can be a handful for the novice when basic instructions assume more knowledge than many pilots have. But you can create and fly a flight plan, practice with the autopilot, and navigate using the menus of the MFD. Working with the G1000, I once counted more than 500 button/switch combinations on a dozen screens. There is one control that has left-right, up-down, and press functions!

Only after that essential level of familiarity has been achieved should a pilot move up to a simulator to integrate the actual flying. Otherwise, there’s too much going on for most of us to divide our time between exploring buttonology and flying the plane.

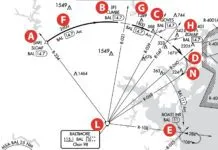

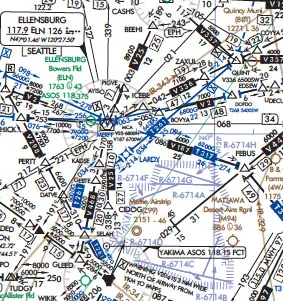

Explore areas beyond your home ’drome to find geography and procedures you don’t encounter every day. In the sim, just relocate yourself, but you can also sort of do that in the airplane. For a ground-based approach, just use a local navaid with the foreign approach (checking for terrain). You can even transpose an approach by creating your version of the other approach’s waypoints. This is where a small group of pilots can share their creativity.

My recent relocation from New Mexico to Florida has presented a different operating environment. I’ve had to become acquainted with the airspace, approaches, obstacles, local standardized operating procedures, and the times of the day best for working practice approaches. The different weather patterns are another moving target that keeps me on my toes. As a CFII, I need thorough familiarity with the local charts before getting a clearance—so I won’t struggle with a vector to an intersection I’ve never heard of.

TAA Considerations

Pilots transitioning to TAA should seek specialized training from a qualified instructor. I took my first G1000 dual in a DA-40. After 2.7 hours, I got a sign-off but couldn’t do much more than tune the radio and find a radial on the VOR. Six months later, I attended a formal Cessna G1000 training course, flying a new Cessna 182. The class spent the first four hours of each day in lecture and then an afternoon flight (a total of 9.9 hours over six days). But I didn’t feel comfortable until I taught a G1000 ground school and put several pilots through their transition.

Integrating handheld equipment is another concern. Tell your instructor about any apps you intend to use. Unless you are already skilled with these, their integration might be left to a follow-up session to avoid overloading what could be an already intense session.

Use Of A Sim

Most, but not all, of the IPC can be conducted in a simulator, flight training device (FTD), or aviation training device (ATD)—either basic or advanced— which are useful tools to bring back awareness and procedural aptitudes.

Redbird, Frasca, Elite, and Precision Flight Controls are popular training devices and even include some common avionics. Panels that approximate different light aircraft might also be available. So, the transition to the “real” airplane can be less confusing.

Airborne

The flight portion of an IPC typically consists of scenarios based on the aircraft and airspace being flown and areas you (or the instructor) feel need work. Knowing the pitch, manifold pressure, and RPM for the different climb and descent configurations will reduce the needed time and scan and ultimately your stress. Keep in mind the refrain, “pitch plus power equals performance.”

Communicating with ATC is vital, so file a flight plan and practice picking up the clearance. After departure, intercept and track your initial course. During the flight, the instructor should present partial panel, deviation, and emergency scenarios.

An IPC can be an extended instructional period over several flights. Each examines the physical airplane skills (i.e., basic stick-and-rudder abilities); the mental competencies (i.e., expertise and ability with aircraft systems); and aeronautical decision-making (ADM).

Publications

The IPC requirements are outlined in §61.57, while AC 61-98D, “Currency Requirements and Guidance for the Flight Review and Instrument Proficiency Check,” provides the overall direction. The FAA provides an optional online support document, “Instrument Proficiency Check (IPC) Guidance,” to structure, conduct, and document the IPC. It provides an excellent appendix with helpful checklists and summary forms.

Consider reviewing the Instrument Flying Handbook and the Instrument Procedures Handbook. An additional resource to help pilots establish their minimums is the FAA Personal Minimums Checklist, a separate topic indeed.

Post-Flight Debrief

Replay the flight with the instructor to discover areas where perceptions and opinions differ and explore those that don’t match. This provides critical insight into your judgment and helps you realize that decisions made during the flight could have been different, and enables discussion of alternatives.

Describe parts of the flight that were the most difficult and phases where you felt uncomfortable. What risks were encountered, and what might mitigate similar risks in the future? How does the flight relate to previous hazards encountered? Discuss “what-if” scenarios. The bottom line will be, “Did you perform up to PTS or ACS standards?” A comprehensive IPC provides an effective IFR refresher.

Consider what type of future training would be useful. Frequent exposure to the academic elements is required. How a pilot selects the topics to review requires some thought. Attending IMC Club sessions is time well spent each month. You’ve probably heard this before but, file and fly the system at every opportunity to refresh your knowledge and skills. It is rare when I don’t learn something on every flight.