Oxygen If You’re Tired?

I enjoyed Victor Vogel’s “Managing Fatigue” in your April issue. I have asked many people and read many articles. No one has ever said, “Why yes, supplemental oxygen will help keep you wide awake.” This has included AME’s, IFR instructors, et. al.

Is there an FAA rule against saying that? Or Am I so different from the rest of the population? Is there fear that not enough pilots carry oxygen, so the plan is not to inform any of them? Is there concern that not all pilots may react so well? I have relied on it so many times and I do indeed regain full feeling of being sharp almost instantly when sucking on the hose. It has not diminished in multi-hour flights.

So I am saying it works for me, well tested. Why are not all pilots told to give it a try?

Lindley Manning

Reno, NV

Lin, the difference here is fatigue versus alertness. While oxygen can and does enhance our mental acuity, it’s not a remedy for fatigue.

Dr. Victor Vogel, MD, the author, replies:

The mechanisms of fatigue and hypoxia are quite different. Fatigue has a number of contributing factors that include insufficient sleep, total time spent awake, and the phenomenon known as “sleep debt.”

In addition, if the quality of sleep is poor repeatedly, chronic fatigue can occur. Alcohol and medications can also lead to what is known as “sleep fragmentation” which involves waking up and going back to sleep several times during the sleep period.

The only known strategy for fighting fatigue is adequate sleep and rest. It is also prudent to avoid alcohol and drugs, maintain a healthy diet, and stay physically active. In addition, avoiding the overuse of caffeine and other stimulants is useful advice.

While the use of supplemental oxygen is advisable by both the regs and as a practical consideration (such as using supplemental oxygen at night above 5000 feet MSL), there is no evidence, and no physiologic reason, to expect supplemental oxygen to combat fatigue.

Dr. Brent Blue, an occasional contributor to IFR and a well-known and highly respected physician active in aviation matters also responded:

I do not know of any study that shows oxygen as an “alerting” substance unless the pilot is hypoxic. I believe hypoxia is far more prevalent than most pilots realize.

Hypoxia is relative. While one pilot may be at his/her full capacities at 90 percent oxygen saturation, another pilot might be slightly diminished.

The FAA rules are misleading and arbitrary which is why Mike Busch and I introduced digital pulse oximetry to aviation in 1995. In our preliminary studies, we noted that oxygen levels dropped in pilots while sitting in the cockpit just from the restricted diaphragm movement in that position—particularly if the pilot had excessive abdominal fat. Even lower altitudes will increase this effect.

If a pilot is flying an unpressurized aircraft at 10,000 feet MSL and lives at sea level, he/she will definitely have relative hypoxia after a few hours in flight. How the pilot tolerates this will depend on age, weight, and underlying conditions. In a pressurized aircraft, a pilot may have relative hypoxia especially if they live at sea level. (A significant contributor to jet lag is cabin altitudes of 6000 to 8000 feet for long periods of time in addition to low humidity and time zone changes.)

I have long recommended that pilots use oxygen for 10 to 15 minutes before landing after a long flight, not to wake them up, but to improve their cognitive function. It will result in better instrument approaches and better landings.

We Can Fly RF Legs

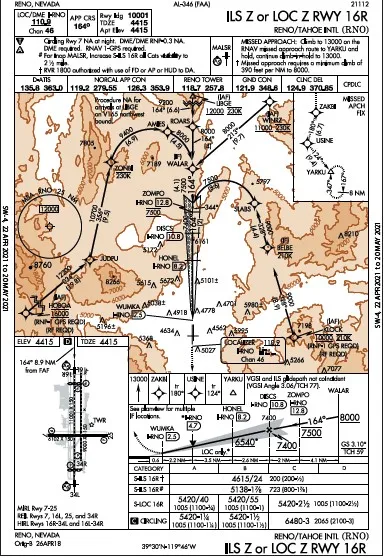

Nice answer to reader’s questions on RNAV (RNP), AR, RF legs at Reno, NV in April Readback. You should note that the ILS Z or LOC Z RWY 16R also has RF legs, but doesn’t require authorization. My Garmin GTN 750 has that in the database and can fly it.

Lee Elson

Carson City, NV

You’re right, Lee. We overlooked the few approaches with RF legs that do not require special authorization. We knew about some, but simply forgot. We’ve gotten a few reader e-mails pointing out our oversight.

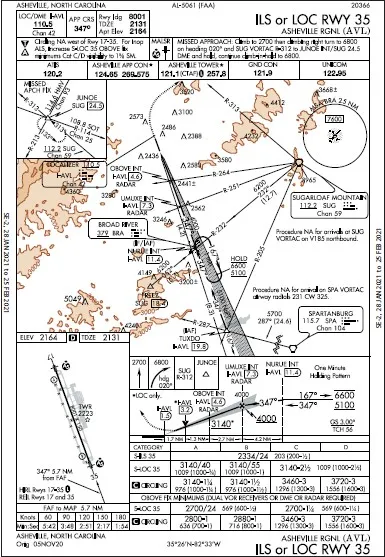

More On Asheville

Kudos for emphasizing so many issues that can frustrate pilots when approaching Asheville, NC in IMC. (“Killer Quiz: Off the radar” in April) Nighttime approaches, of course, are expected to be more hazardous, especially given the peculiarities of Asheville’s radar coverage. Beware that mountains will usually obscure your view of the airport when approaching at night from the west (even in VMC). Circling west of the airport is forbidden for obvious reasons.

Daytime has its own set of issues— mostly weather in the form of fog. Being in the Smokies, this is to be expected. However, unlike most locations with early morning fog, it tends to linger much longer here before burning off, frustrating departures. (Interestingly, this never seemed to bother me until I swapped my twin for a single, at which point it changed from an irritation to a concern.) Plus, there are very few nearby departure alternates. Plan accordingly.

In flying into KAVL over many decades, it seems that I encountered icing and thunderstorms more frequently here on the east side of the Smokies than I did in nearby areas like Knoxville or Greenville-Spartanburg.

Instituting GPS approaches into AVL has reduced pilot workload and the likelihood of “task saturation” during descent and maneuvering to the IAF for night IMC.

Charles Burnett

Germantown, TN