Not long ago, I was kibitzing with Mike, my longtime friend and hangar-flying buddy. Aviation was, of course, the topic of choice. I

was in the midst of a compelling (or so I thought) “there-I-was” story in which I referred to a colleague as a “good” pilot. Mike stopped me with a deceptively simple question: “Paul, what does it mean when you call someone a ‘good’ pilot? What makes a pilot ‘good’?”

I had to stop and think about that one. As I rapidly replayed some recent conversations in my head, I realized it was common to hear things like, “He’s a good pilot, but he’s weak on procedures.” Or, “He’s a good pilot, but he lets the plane get ahead of him.” What were they thinking?

Both of those “good” pilots probably had solid stick-and-rudder skills. But “good” and safe flying, especially in the complex IFR environment, clearly require a great deal more. My eventual response to Mike’s question was that a “good” pilot is someone who demonstrates a mastery of the aircraft in terms of flying skills, knowledge, and superior situational awareness.

Having since reflected more on this topic in the context of my long experience in the aviation-training world, I think that making a pilot “good” in terms of flying skills and knowledge is a fairly straightforward process. Getting to superior situational awareness, though, is a different and more difficult proposition—and, sadly, accident reports bear witness to how an otherwise “good” pilot’s deficits in this key part of the trifecta can be tragic.

There is an unfortunate myth that it’s not possible to teach things like judgment and situational awareness (SA). In my view, instilling superior SA is fundamentally about developing two habits. The first is reviving the constant stream of genuinely curious “how” and “why” questions we all pestered our parents with during the toddler stage. The second is cultivating a healthy “trust but verify” skepticism that could also be framed in terms of, “What could possibly go wrong?” (Hint: everything.)

If you constantly ask and honestly answer these questions, not only do you have situational awareness, but you are well on the way to resolving situations that—as the cliché goes—might otherwise require the use of superior skills. (“A superior pilot is one who uses his superior judgment to avoid those situations requiring his superior skills.”)

Let’s explore how we might instill these habits in those pilots we teach or mentor, and practice them in our own flying.

Tap into Toddler Talk

There are studies showing that kids in early childhood can ask as many as 200 to 300 questions each day. I haven’t (yet) kept count of the questions I mentally ask and answer on a typical IFR

flight. But when I ponder the complexities of the IFR environment,

that’s probably a reasonable target. I owe this particular habit to Field Morey, one of my earliest aviation instructors who has been a lifelong mentor to me and many others.

Back when I was at the toddler stage in IFR flying, Field taught me to ask a lot of questions. For example, we used a logical sequence to brief the assigned approach. But we weren’t finished. I can still hear Field’s next question, one that I always ask myself and flight crew members after we finish the briefing: “How will we get established on this approach?”

In today’s IFR environment, it is easy to assume radar vectors. But, it’s far better to assess than assume. So, we ask more questions. Field’s favorite mnemonic guide for asking the right SA questions for this phase of flight was SHARP:

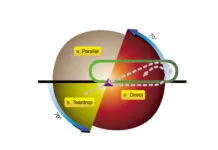

S: Is it a straight-in approach? How do you know that? (Hint: Does the transition include the “NoPT” notation?)

H: Do we hold in lieu of a procedure turn? Approaches increasingly use a holding pattern in lieu of PT for entry. A key question is how to enter that hold. A GPS (or FMS) can certainly take the pain out of answering that question, but SA requires that you ask a few more. Just for example, once you arrive at the holding fix, do you have to fly the outbound leg to be established? When you cross the holding fix, will your autopilot start the descent without any further action? When it comes to automation by the way, the number of SA “how” and “why” questions you should ask could readily reach that “toddler twohundred” level.

A: Is there a DME arc? These, too, are increasingly rare. But as long as they are on published IAPs, you need to know how to fly them either manually or via automation. Do you?

R: Will we get radar vectors? If so, when? Be certain you know the operating hours and capabilities of the controlling facility.

P: Do we use a procedure turn (PT)? If so, how do we enter? Since approaches with a procedure turn depicted the way many of us remember (e.g., the classic 45/180) are becoming rare, your first question might be asking why you need this skill. But you do.

Just as answering a toddler’s first “how” or “why” question leads to many more, you will have noted that each of the SHARP questions opens the door to additional layers of essential inquiry. You may also have observed that some of those new queries lead to those less comfortable but critically important, “What could possibly go wrong?” questions.

Trust (Maybe), Verify (Always)

What could possibly go wrong? Everything— and for an instrument pilot, even little things can cause big trouble, putting you on a path to a flight-threatening outcome. Consequently, maintaining superior SA requires pondering a steady stream of “what-if” scenarios. I am fortunate that Field drilled me in the SA skill of expecting the unexpected. Here are a few examples of situations in which trust-but-verify SA made a difference.

There wasn’t much automation in GA when I was learning to fly IFR. I have learned, though, that maintaining SA via the what-can-possibly-gowrong mentality is possibly even more important in a world where the use of automation is expected and often even required. What if your automation fails, or your flying partner botches things with the box? That happened to me during a single-engine event on a recent Part 135 checkride. The details of how it happened are less important than the outcome.

Having asked myself the right questions as we set up the approach gave me the SA to quickly realize what had happened and what it meant—specifically, that I had no FMS navigation available and could not use the autopilot on the missed. There was no time to waste wondering what went wrong. I simply told my right seat partner to dial in the frequency of the MAP VOR and used it to proceed direct to the fix and I entered the hold sans automation.

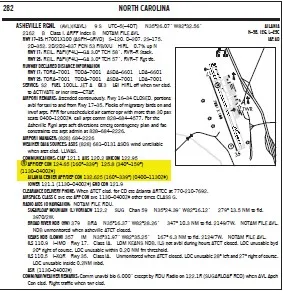

What could possibly go wrong? If you are departing Asheville (KAVL), NC, a scenic airport in a mountainous area of North Carolina, it pays to ask yourself lots of questions about how you will depart—especially if you are operating during those times of day (i.e., after 0400Z) when Atlanta Center handles IFR departure and arrival traffic at Asheville. Do you know how to find and use the Obstacle Departure Procedure (ODP)? Can you comply with the required climb gradient? If not, what are your options?

You also need to be in intense Q&A plus trust-and-verify modes for an arrival during those times when Center is the controlling facility. Center can’t provide vectors, because radar coverage isn’t low enough. So, as you approach KAVL, you might hear something like, “Proceed direct BROAD RIVER. Maintain 7000 until established on a published segment of the approach. Cleared ILS 35.” A lot could go very wrong if you don’t know or recall that “published segment of the approach” is code for “you are on your own.”

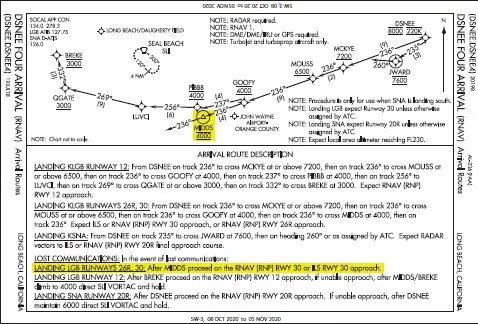

Procedures in busy airspace, like Long Beach’s DSNEE ARRIVAL, also require high-intensity SA. This arrival is one of many in the busy SOCAL airspace. Like others in busy areas, this one includes an Optimized Profile Descent (OPD). OPDs exist to help ATC manage traffic flow, minimize communications, and, in many cases, comply with noise abatement over heavily populated areas. A quick look at the complex chart for the DSNEE arrival makes it clear that flying an OPD requires both study (i.e., lots of questions) and preparation.

What could possibly go wrong? If you fail to prepare for an OPD like the DSNEE arrival, it is a near-certain path to losing SA and getting seriously behind the aircraft. There is a mix of “at or above,” “at or below,” and “hard altitudes.” Some avionics systems enable the autopilot to navigate this procedure both laterally and vertically, making every restriction without any problems. Others don’t.

My employer has a fleet of Lear 31s and Lear 35s, all with different avionics configurations and capabilities. The last one I flew into KLGB did not offer the option of coupling the autopilot to the DSNEE arrival’s VNAV profile. Had I failed to ask myself the right questions and kept my brain in trust-but-verifyeverything mode, many things could have gone badly wrong.

One Plus Two

This is a good example, so let’s walk through it together. Together, let’s walk though some of the mental maneuvers I made to ensure that my aerial maneuvers kept us safe and legal.

First, what is the necessary rate of descent? A rule of thumb is 3:1, 300 feet per mile. The first hard altitude is 28,000 feet. If you’re at 36,000 feet, multiply the altitude to lose by three and start descent at that point. (8000 × 3 = 24 miles before the restriction). Use the same method to manage and monitor progress between fixes on the arrival.

Next question: What is the required rate of descent in feet-per-minute? Dig into your memory for the simple rule of establishing rate of descent required to maintain a three-degree glide slope on an ILS: Multiply groundspeed by five to get rate. In the case of flying an ILS at 150 knots groundspeed, a rate of 750 FPM will keep you close to the glidepath. What could go wrong? Winds can and do change, so monitor your progress on the glideslope to maintain SA and adjust as needed.

Will this work on the arrival? At 400 knots groundspeed you’ll need a roughly 2000 FPM descent. What could go wrong? Those calculations assume that the angle between waypoints on an arrival is three degrees. Is that the case for the procedure you’re flying? If not, what adjustments must you make to your descent profile to comply with the altitudes? In these instances, your SA is critical. To provide a buffer, some pilots multiply by six rather than five and use the result to level off before the required waypoint in case a speed reduction is required at the fix.

So what if I’m bad at mental math? You normally have lots of help these days from automation and EFB apps, and those in a crew environment can also “phone a friend” in the other seat for both calculation and confirmation. But you still need a basic sense of the calculations and a solid grasp of what TLAR (“that looks about right”) would be. (Note that the corollary to TLAR is TARA—“that ain’t right. Adjust.”)

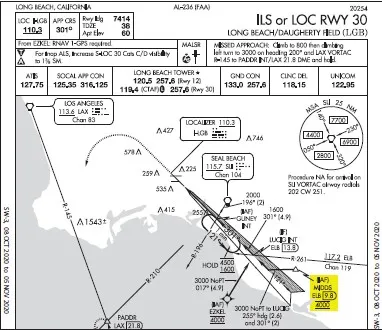

Another tricky point is that, MIDDS, the last fix on the arrival doubles as the IAF on the ILS 30. There is so much information for this arrival that the government version puts it on two pages. A note says to expect the ILS 30. In my recent flight, though, the approach clearance did not come in the typical format of position from fix, turn, altitude, and clearance. In this case, once we crossed MIDDS, we were simply cleared for the ILS 30. Note that

the chart does not say to expect radar vectors for the ILS 30. Make certain that you and your avionics are set up for the approach.

Master of My Situation

In one of the many memorable scenes in “Casablanca,” one of my all-time favorite flicks, a main character proudly proclaims, “I am master of my own fate”—an assertion immediately contradicted by the next character’s entrance. Don’t be that person. Be master of your fate, ensuring that high SA always makes you the master of your situation.

Major SA Points

A/FD: Review the Chart Supplement to make sure you understand the capability and hours of the controlling facility. After 0400Z, the absence of the symbol ® means Atlanta Center does not have radar coverage for KAVL.

DSNEE: The arrival route description for KLGB Runway 30 shows that you will cross MIDDS at 4000, then track outbound on a heading of 236 degrees. It also says to expect the ILS 30 (does not say radar vectors).

KLGB ILS: The approach chart for KLGB ILS 30 shows MIDDS as the IAF with a transition to the final approach course. Radar vectors not provided.

Thanks for the complement Paul. I have pleasant memories working with you over the years. It is extremely rewarding to see you carrying the torch for excellence in IFR flight training. Keep up the good work.

Your friend always,

Field

“Dig into your memory for the simple rule of establishing rate of descent required to maintain a three-degree glide slope on an ILS: Multiply groundspeed by five to get rate. In the case of flying an ILS at 150 knots groundspeed, a rate of 750 FPM”

I think an easier rule of thumb is this (using above numbers):

150 GS. What’s half of 150? 75. Add a 0 to get the required rate of descent.

For my brain, this is much easier than multiplying times 5.

Great tip. Thanks David.