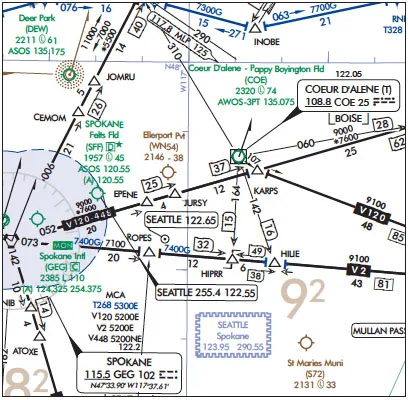

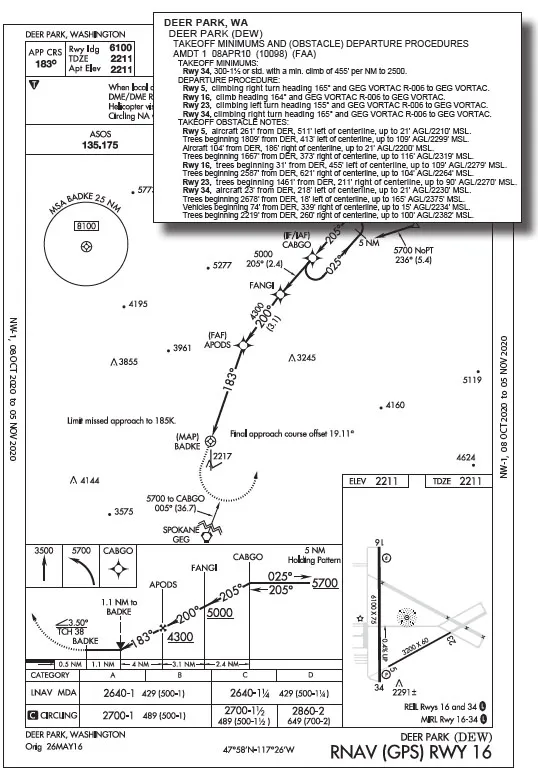

Flight-planning your Washingtonstate mini-vacation taught you a lot about identifying obstacles on approach. Overall, IFR into Deer Park won’t be too onerous for terrain or procedures. But it does mean unseen obstructions—some close to the final approach path (see “Obstacle Hunt” in last month’s IFR). It took time to piece together the details using all the charts and airport notes you could find. But now there’s still the rest of the RNAV 16 approach to brief.

Missed Approach Obstacles

The published missed is typical: “Climb to 3500 then climbing left turn to 5700 direct CABGO and hold.” But there are, best you can tell, three sets of obstacles (man-made towers) close to the airport. One, just west of the departure end of Runway 16, appears to be less than 10 feet high, and early on in the approach briefing you saw the obstacle symbol on the plan view. The other close-in obstacle, just east of the south end of Runway 16, appears only on the airport sketch, so you hadn’t spotted it until now. It shows an elevation of 2291± feet, meaning the elevation accuracy is “doubtful.”

After reading in the AIM that obstacles aren’t always shown in the same place, you note that there’s no guarantee they’ll appear at all. As the Chart User’s Guide says, “Any obstacle which penetrates a slope of 67:1 emanating from any point along the centerline of any runway shall be considered for charting within the area shown to scale. Obstacles specifically identified by the approving authority for charting shall be charted regardless of the 67:1 requirement.”

To picture how this would work for 6100-foot Runway 16/34, picture 50-foot obstructions 3350 feet from the midpoint of the runway—that would put them just off the ends. Then picture 100- foot obstructions another 3350 feet out (6700 feet from the runway midpoint) and you get an idea of how objects would get flagged. In essence, shorter obstacles close to the runway have as much chance of getting space on a chart as taller obstructions further out.

Given the unfamiliar territory, marginal weather and a 19.11-degree final approach course offset, plus crosswind, you pad personal minimums. On the approach profile view it’d be best to use the visual descent point, 1.6 NM from the threshold, as the MAP, rather than BADKE on a half-mile final.

The AIM (Chapter 5, Section 4), says a VDP is where “normal descent from the MDA to the runway touchdown point may be commenced.” Since the requirements for landing under §91.175 tie into that, consider the VDP as where you have the option of continuing below MDA—if you see any of the required visual cues—with a moderate descent. So you build in an extra mile from the threshold to make the land/miss decision, and add more visual elements to continue. Tell yourself that the PAPI, REIL, and runway numbers must be in sight. Otherwise, fly the missed approach from the VDP.

Don’t forget to check the profile view for the gray stipple between the VDP and threshold. The Instrument Procedures Handbook explains: “For RNAV approaches only, the presence of a grey shaded line from the MDA to the runway symbol in the profile view is an indication that the visual segment below the MDA is clear of obstructions on the 34:1 slope. Absence of the gray shaded area indicates the 34:1 OCS is not free of obstructions.” The OCS, (Obstacle Clearance Surface) can be any slope designated for obstacle flagging. This slope’s steeper than the 67:1 slope for obstacle charting criteria, but it’s in a critical location. With no gray stipple on the profile view, is there a way to figure out what’s there?

Found ’Em

You learned from past flights out west that the easiest thing to skip when briefing an airport is the departure procedure. For KDEW you’ve so far briefed airport notes and approach charts, but it’s smart to review the departure (for each runway that could potentially be used) before flying in. This could be handy not just when leaving, but on a late go-around due to flight conditions, or someone/something popping out onto the runway. So jump ahead to the departure phase for Deer Park in the “Takeoff Minimums and Obstacle Departure Procedures” publication. (Know that the FAA catalogs all approach and departure procedures online under “Terminal Procedures.”)

There, find instructions for departing Runway 16: “climb heading 164° and GEG VORTAC R-006 to GEG VORTAC.” That’s the Spokane VORTAC.

Further down are obstacle notes, more than what shows on the chart: “Rwy 16, trees beginning 31’ from DER, 455’ left of centerline, up to 109’ AGL/2279’ MSL. Trees beginning 2587’ from DER, 621’ right of centerline, up to 104’ AGL/2264’ MSL.” And here’s what you’ll overfly coming into Runway 16: “Rwy 34, aircraft 23’ from DER, 218’ left of centerline, up to 21’ AGL/2230’ MSL. Trees beginning 2678’ from DER, 18’ left of centerline, up to 165’ AGL/2375’ MSL. Vehicles beginning 74’ from DER, 339’ right of centerline, up to 15’ AGL/2234’ MSL. Trees beginning 2219’ from DER, 260’ right of centerline, up to 100’ AGL/2382’ MSL.” Ah, here are the rest of the obstacles. Some, like the trees 18 feet off the centerline, further emphasize that your task is to mind all published courses and altitudes, and by all means stay on the centerline.

Off you go. An hour out on Victor 2 from the east, the last weather has gone down a tad to 1600-2 and light snow. So you expect to break out around 3800 MSL, inside APODS, the FAF. Vectored off the airway near Coeur D’Alene, you’re cleared direct CABGO for the approach. From there, report established on final following the hold-in-lieu-ofprocedure turn (HILPT).

On final you’re in a crab against the southwest 15-knot wind. It’s tempting to let the needle wander left given the offset course of 183 degrees, plus an additional few degrees left in the sight picture to correct for the wind. Looking left of the nose, you’re searching for the PAPI’s lights. Four miles from the threshold, between the FAF and VDP, you’re headed for a rounded-up MDA of 2700 feet when the runway end lights and PAPI come into view. Now you just want to see the “16” to continue.

But two miles later, a snow shower blots out the lights. You think about changing the early-missed plan and leveling off at 2700 until BADKE. That’s only a half-mile from the threshold of the 6100-foot runway. With those big Cessna flaps half deployed, you could practically hover at MDA until the numbers. If it looks okay there, add full flaps and easily lose another 500 feet to make the first half of the runway.

But that wasn’t the plan. You resist the temptation and add full power then pitch for a go-around. Stay on course during clean up until reaching 3500 feet. The climbing left turn is where things calm down enough to get back on with ATC. You request the same approach, figuring there’s a good chance the snow shower will pass by and you can get the visual elements you want.

The second procedure works as planned, with the snow clearing up and the visibility improving to four miles, allowing all the lights and paint to come into clear view. What you realize when gliding past the threshold is that you never did see on the first approach NW-1, 08 OCT 2020 to 05 NOV 2020 NW-1, 08 OCT 2020 to 05 NOV 2020 all the aircraft, vehicles, and trees you passed by, but knew were there, thanks to the comprehensive obstacle search. It would’ve been quite risky to change your approach plan on a short, low final in the snow, attempt to press on and maybe even wander off course in a high-workload moment. So the first plan was a good one, and now it’ll save a lot of time when you’re ready to depart. This time, though, you’ll wait for better weather.