With modern avionics, radio failures are rare but not nonexistent. Light aircraft still have com vulnerabilities from electrical faults, frozen touchscreens, broken buttons, etc. And, many of us still have some old radios. So you still need to know your lost-com procedures, but even those might not cover all the bases.

The Route

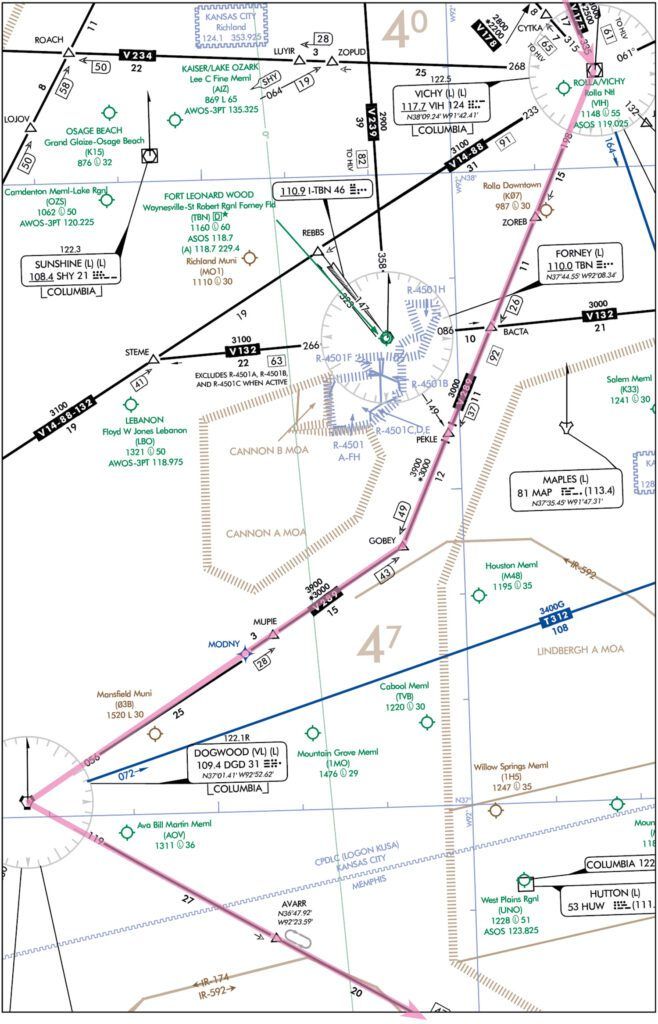

From Columbia, Missouri, the direct route to North Little Rock, Arkansas, is simply straight south for two hours. But with military airspace in the way and a Class C airport near the destination, you’re occupied with route planning. There’s fuel management too; ceilings will get lower and procedures require flying past the destination to commence an approach. So start at the departure point and pick your way through.

From Columbia, Missouri, the direct route to North Little Rock, Arkansas, is simply straight south for two hours. But with military airspace in the way and a Class C airport near the destination, you’re occupied with route planning. There’s fuel management too; ceilings will get lower and procedures require flying past the destination to commence an approach. So start at the departure point and pick your way through.

About 60 miles in, there’s an MOA and a cluster of Restricted Areas overlaid by what appears to be a Class D military airport. It’s difficult to tell on the chart, so look up the Chart Supplement and see that Fort Leonard Wood is one of a handful of joint-use military airports open for public use. Enough review. You’ve got to get going.

You get more details on the weather. The 30-knot west winds aloft will slow you down in cruise, and KORK is reporting winds southwest 18 to 25 knots, visibility 3-5 miles, 800 feet broken for the next few hours. So, you’ll have to fly past the field for one of two north-facing approaches. While there are two runways, and you prefer 23—it’s longer and into the wind—only 35 and 5 have approaches.

That means a circling approach to 23. Do this by breaking off from the final course about a mile out to enter right downwind—you did check on the published traffic pattern. So overfly the runway for the downwind on the north side and maintain the circling MDA of 1040 feet until your landing descent.

Finally, you file for KORK at 6000 feet: HODGS VIH V289 GOBEY CEMUK BENIT LIT—which follows some airway segments to bypass restricted airspace early in the trip. It’ll also get you to the Little Rock VORTAC southeast of the destination and from there, hopefully vectors to the approach. However, the route cuts through a big three-part MOA, but you leave that in. Not only are you behind schedule, there’s no quick way around, so you decide to bet on the tiny chance you can go through, and otherwise leave it up to ATC for re-routing. At least the alternate was a quick pick: Use the main Little Rock airport—just a few miles away with adequate weather.

Tough Call

Traffic at Columbia was thin, so within minutes of startup you had climbed on top of a 4000-foot overcast. The level-off at 6000 feet made for a smooth, blue ride. But just a few more miles down the road, another thin but solid overcast shelf slid overhead. Then, you get a 10-degree right turn (vector for traffic).

A minute later, an early re-route comes across—present position direct Vichy (VIH) V289 DGD V159 ARG V305 LIT destination. No surprise; this takes you the long way around all the military airspace, but does let you scoot between the Cannon and Lindbergh MOAs. At least you can pop in the new fix after VIH and add the rest as you go.

Reading back the instruction only gets to “present position” when the navcom goes dark. Could it be the screen? No such luck. Neither PTT button works, so you know it’s dead. For now, your first thought is: “I can’t communicate, but I can navigate via the portable.” Next thought: “There’s a procedure for this.” All the instructions under 14 CFR §91.185 aren’t exactly memorized, but you do remember the key items: If IFR, use the most suitable routing and altitude based on clearances or expectations. And, “If the failure occurs in VFR conditions, or if VFR conditions are encountered after the failure, each pilot shall continue the flight under VFR and land as soon as practicable.”

Presently, you are technically in VMC—more than 1000 feet on top of the clouds and well more than 500 below the overcast above. But you can’t descend VFR through clouds, so if you must complete the flight under IFR, go with the assumption that you received, but didn’t successfully read back, the amended clearance. This was during a vector, but this first part is easy. See (c)(ii): “If being radar vectored, by the direct route from the point of radio failure to the fix, route, or airway specified in the vector clearance;”… That’ll work for now—turn back to VIH. After that, you decide to follow ATC’s intention to have you fly the new route and bypass military airspace.

Next, how high: Your present cruise altitude of 6000 feet is above the MEA and it’s what you filed. Later you might have to fly an approach through busy airspace into North Little Rock. But for now, there’s time on the current route to mentally regroup and watch for a break in the clouds.

Good to Know

You’re prepared to take a pebble from both IFR and VFR buckets to continue: You fly the IFR route you received. If ATC is unsure of your plan, they’ll see you on radar. If you can swap that for VFR to land somewhere, great. That’s acknowledged in the AIM’s discussion of §91.185, which starts out with the disclaimer that the reg can’t cover every situation. Oh, and you can squawk either 7600 or, if invoking emergency authority, 7700. Since you can’t call up other frequencies like a FSS or 121.5, you cross those off the list.

The re-routing added about 45 minutes to the flight, and you departed late. But in reality, these changes never discuss ETAs; that’s all coordinated in the background. Still, if you knew you were early and had to continue IFR, the rules would have you holding over the clearance limit (here, it’s the destination) then proceeding to an approach fix to make the timing match your ETA. It’s likely it won’t come to that this time, but you realize that you rarely pay attention to flight times when filing; maybe it’s time to start.

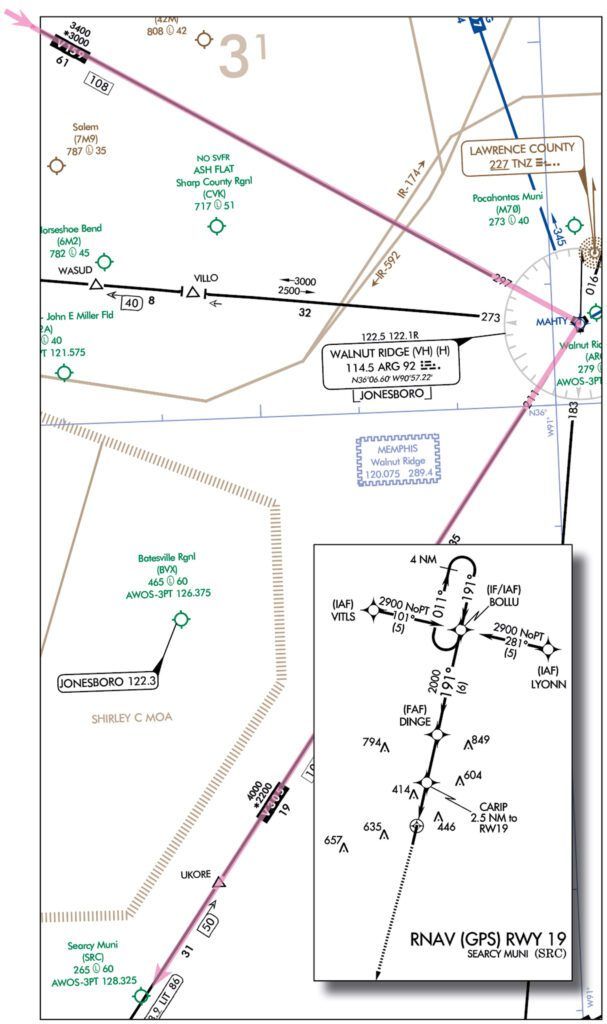

Finally, the clouds just ahead open an escape hatch and Searcy Muni is reachable in VMC. But as you’re unfamiliar with the airport and any local obstacles, you take another rock from the IFR bucket and, using your backup electronics, follow the RNAV 19 approach from BOLLU. This’ll require a quick descent through the biggest gap in the clouds ahead, but as long as you can level off at 2900 feet remaining under VFR, it’ll work.

Well, call it VMC—the cloud clearances weren’t quite enough as you overflew the initial fix before continuing the approach descent to 2000 feet, but you still felt that diverting here was safer than pushing into Little Rock. You can make a phone call from the ground to sort out the rest. So the last reroute, initially a groaner due to the added time and fuel, turned out to lead you to better weather. Your portable but reliable ADS-B In tool was also another lifesaver, as were the backup charts and moving map. But maybe filing more thoughtful flight plans will go a long way to avoiding headaches if anything goes wrong. That’s cheap insurance. A second radio is not, but you decide it’d be well worth it.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. She flies a vintage Piper 235, radios and all, and is looking forward to installing new instruments and navcoms.