While no two approaches or departures are alike, most fit a template. Others need just a little more review and planning to be on top of things, and require an open mind (and open eyes) to avoid problems you didn’t expect.

Extra Steps

After deciding to step up from your Cessna 172, a nice-looking 182 came up for sale not too far north of you. It has been based for the last several years at Little River, California. Your mechanic friend agrees to assist and fly there with you from San Carlos to get a first look. He plans to take along a bag of tools while you pack a cooler of snacks and sodas for the trip (with promises of a full meal after). Since the whole thing will take the better part of a day, you plan to take off early in the morning. The flight from San Carlos will be less than 90 minutes.

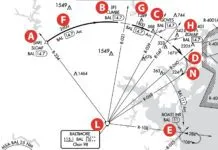

After an estimated two-hour session at KLLR to look things over, you’ll decide whether to arrange a ferry flight to your home base shop for a pre-buy on another day, or decline to make an offer. Excited about a possible purchase, you also look forward to a coastline trip to a new airport. During the flight planning, you find a commonly used route from KSQL to KLLR, where the Mendocino VORTAC serves as a launching point for coming and going:

STINS V199 ENI

It’s CAVU at San Carlos for the day, so no issues there. Meanwhile, the weather at Little River started out with low clouds and mist, but that should clear up sufficiently on arrival at 9 a.m. local. The catch is that Little River has minimal weather reporting. It has something called an AWOS-AV. According to the obscure Advisory Circular 150/5220-167E, the “A” is for altimeter and the “V” is—you guessed it—for visibility. What, no wind or clouds? Not with the AWOS-AV, so refer to the weather imagery.

And to make planning even trickier, there aren’t any airports with anything better for reporting or forecasting for at least 20 miles. There aren’t many airports, period. There is Ukiah, 27 NM southeast, but it’s further inland and you won’t want to rely on that for weather as it relates to airports on the shoreline. That means using the national graphical maps, which include LIFR, IFR, and MVFR forecasts. These take extra time, but at least they’re interactive for hourly projections.

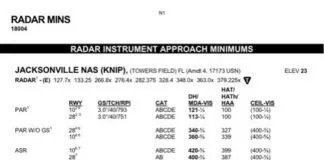

A few minutes of clicking around shows it’ll be a bit low due to the morning scud; at departure time clouds were up to the basic IFR threshold of 500-1000 feet for ceilings, one to three miles visibility. Winds will allow a straight-in on the only approach, RNAV 29, and it will be above the 1000-1 LNAV minimums. And while you almost always file an alternate unless it’s CAVU on both ends, you wonder about the dearth of nearby airports, and what would even qualify.

Maybe, technically, you don’t need one and can skip it. That’d require at least 2000/3 for one hour before and after the ETA at Little River to comply with §91.169 (b)(2)(i). The clouds might stay low but break up enough to be called scattered, which is not a ceiling for these purposes. But the visibility is on the edge of requiring an alternate that fits §91.169 (c)(1)(i)(A) and (B). One that will work is Sonoma County, 63 miles southeast, complete with ATIS, TAF and tower. You’ll have plenty of fuel even after flying there from Little River, satisfying §91.167(a), (b)(1), and (2)(ii)—all the bits that apply to airplanes.

Long Final

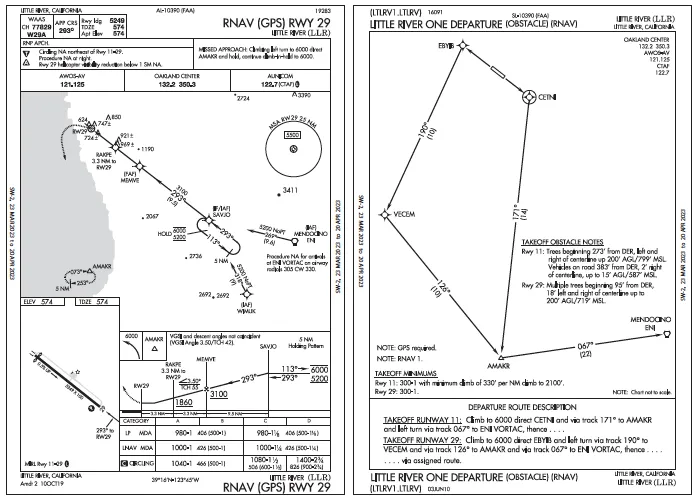

Takeoff is on time and you hope conditions improve at Little River. Even if it clears up, you’ll fly the RNAV 29. The approach will start at ENI and lead to what amounts to a 16-mile final. That’s unusually long and starts from between 5200 and 6000 feet, then steps down to 3100 feet, with 9.5 NM to achieve that. Sounds leisurely until the final segment, where the trees are apparently tall enough and close enough to the runway ends to warrant steeper approaches (which means steeper departures).

As an app geek, you carry two EFBs to have all the various features for airport data handy. One is WingX, which notes Runway 11’s approach slope: 31:1 over trees. Good to know for a missed or takeoff from 29. Anything else not revealed on the en-route chart? This looks like a job for ForeFlight.

While KLLR isn’t in the mountains, it has enough obstacles to have the little terrain icon covering the area 10 miles around the airport. Open that and see “max terrain” of 1745 feet MSL. It’s not clear exactly what that points to but there is an 1190-foot obstacle right off the approach centerline between MEMVE and RAKPE (1190 plus terrain elevation would be about that.)

Just stick to the approach to avoid doubts. And while the 3.5-degree glidepath is noticeably steeper than the standard, it’s a non-issue for big-flap aircraft like the 172. At SAVJO, you start depending on visual cues to determine the cloud conditions, and you do get below a scattered layer around 3100 feet. However, the forward vis is still marginal—not more than three miles, and of course there’s haze from the sun in your eyes. So despite being out of the clouds, you remain glued to the panel until minimums and then use the runway paint to stay centered for landing.

Departure Decisions

The 182 inspection took closer to three hours as the aircraft started to look like a good buy as you examined the engine and airframe. Meanwhile, the clouds cleared with an estimated 3000-foot scattered layer and visibility also improved as the sun moved over enough to make takeoff more comfortable. That is, if you again opt to follow what’s provided and fly the obstacle departure procedure. This too is a bit unusual, as you haven’t seen many ODPs of this size and shape. Other than flying a large box to get to the en-route fix, returning to San Carlos is just the same route in reverse from the Mendocino VOR, which happens to be the end point for the ODP.

The wind is unchanged, so use Runway 29 again. The ODP says to “climb to 6000 direct EBYIB” How far is that? The ODP doesn’t say, so get a flight plan going online, which still doesn’t give the mileage for that first line. Turn to either EFB and see it’s 2.4 NM from KLLR to EBYIB. No way you’ll be near 6000 by then, but it’s not a concern as EBYIB is on the shoreline and the two fixes after that are over water. And there’s no climb-in-hold instruction, so the only concern is the initial climb over the trees surrounding the airport.

And with temperatures reaching 20 degrees C, you wonder if you need to leave the mechanic behind, which he didn’t find at all appealing. So you pull up the 172’s climb performance in the POH, which shows about 1600 feet required to clear a 50-foot obstacle at maximum weight. You’ll be lighter than that and, by the way, with the temperature penalty figured, it’ll take about 14 miles to reach 6000 feet, maybe at VECEM or a little past. You also note with relief that the air’s dry with a 15-degree dewpoint spread, so humidity won’t add to the problem.

After all that work between the two of you, hopefully the next trip to Little River will be to test-fly the 182 and continue on home for a pre-buy. And now you’re familiar with the procedures there and the 182 is in many respects just a bigger version of your airplane. Still, the performance and weather will be different next week, so you’ll be sure to plan out another (non-standard) arrival and departure.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in southeast Wisconsin. Known as the local EFB geek, she likes to choose from her vast collection to fit a variety of missions—from low-and-slow in a two-seater to high and fast in a corporate jet.