Thanks to some typical spring weather in the air, it’s cloudy, hazy, and breezy at Chadron Muni, Nebraska. But you’re well briefed on what to expect while flying the RNAV (GPS) RWY 21 approach procedure. Given the conditions and this being a new destination for you, it turned out to be a smart move to analyze not just the approach, but the rarely used performance numbers for the Piper Arrow you fly. And on the two-hour leg from the southeast, there was extra time to brush up on the regs and even learn something new.

Check Your PT

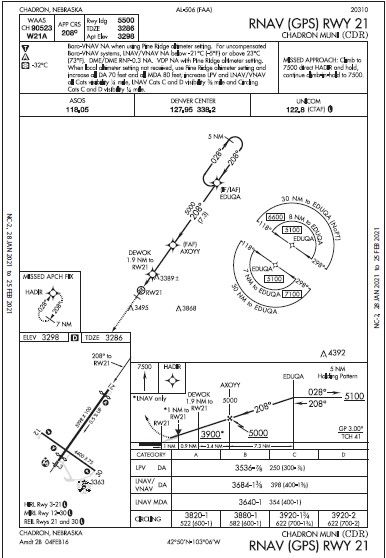

A WAAS GPS is on board, so plan for the LPV 21 approach, with a DA to 3536 feet (250 feet AGL). The two-mile visibility and 400-foot overcast is predicted to improve to 400 scattered and three miles around the ETA, so odds of a fullstop landing are good. But the approach lacks initial fixes for an easy “T” course with base turns to final.

There’s just one IAF, EDUQA, with a hold-in-lieu-of-procedure turn (HILPT). Might hafta fly it unless vectored or cleared otherwise, or if arriving within the northeastern half of the Terminal Arrival Area, which notes “NoPT” at the outer ring. But you’re coming from the southeast and—unless you arrange for vectors in advance—you’ll fly the HILPT. It appears that a teardrop entry would be best.

Then, can you continue the final approach inbound once making the teardrop turn to the 208-degree course? Or do you fly a full lap in the holding pattern, standard turns, 5-NM legs? Unless you’re assigned to hold at EDUQA (not just to reverse course) or you ask for and get a clearance to hold, just fly the teardrop and then head on in. See the HILPT section in the Instrument Flying Handbook, Chapter 1: “The holding pattern maneuver is completed when the aircraft is established on the inbound

course after executing the appropriate entry … additional circuits of the holding pattern are neither necessary nor expected by ATC.” (See “Hold Vs. HILPT,” IFR March 2017.)

Runway Review

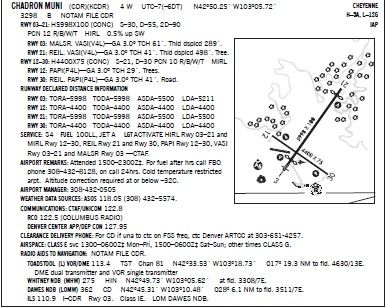

Next, get an airport orientation. Your first go-to for an overview is the airport sketch provided on government approach charts. It shows 3/21 is 5998 feet long—plenty for the Arrow. But the displaced threshold symbol on both ends means there’s less distance available. Jump up to the top of the approach chart and find the runway landing length is 5500 feet. Still enough, but it’s worth getting details on the displaced threshold. While you’re at it, might as well brief the runway markings and lighting. With low ceilings and visibility, it’s useful to know what’s there (and what’s not) when breaking out into visual conditions.

Jump back down to the airport sketch and see that there’s more information on that indicated by the runway Declared Distances symbol, “D”. To confirm the lengths of each part of the runway, look elsewhere and pull up Chadron’s Chart Supplement entry. There, it says the displaced threshold for Runway 3 is 289 feet; for 21, it’s 498 feet. This means if landing on 21, the displaced threshold of 289 feet is useable for landing rollout. Seems like overkill here; you’ve landed comfortably on runways half that length. But those were visual approaches or VFR flights. Things won’t work the same on an IFR approach in low weather, (Queue foreboding music.] as you’ll come to see. Challenging conditions like turbulence, gusty winds, or airframe ice on descent can require a lot more concrete.

Before adding in any weather factors, flying an approach glidepath (RNAV) or glideslope (ILS) to the runway already makes the landing distance longer than you might achieve on a visual. You’ve seen this; the wheels squeak on a good thousand feet or more past the threshold. For this approach, there’s a published standard glidepath of three degrees, with the TCH (Threshold Crossing Height) of 41 feet. How much runway will it take to complete the landing from 41 feet?

For starters, know that if flying the final segment at a groundspeed of 80 knots, the time would be 4 minutes to

fly the 5.3 NM between AXOYY and the threshold. Looks normal so far. Approaching the threshold, there’s naturally a gradual decrease in airspeed/ groundspeed to round out, flare and land, so for simplicity assume the groundspeed decreases to 60 knots at the threshold and remains constant from there.

Hold that thought and figure landing distance. Note that the 41 feet for the TCH is close to the hypothetical 50- foot obstacle used in performance data found in aircraft manuals/handbooks, so have at it. Using the tables for your 60s-era Cherokee Arrow, first get into Fahrenheit and miles-per-hour mode to use the density altitude and landing distance charts. The altimeter is 29.82; pressure altitude at KCDR is 3398 feet. Temperature of 70 degrees F results in a density altitude of 4600 feet. At full flaps, no wind and gross weight, landing distance over a 50-foot obstacle is about 1450 feet. In reality, you’ll be lighter with some headwind component. But that’s offset with an expected faster approach speed (at least 5 MPH) plus partial flaps due to the turbulence, so use 1500 feet as a conservative estimate.

Think TDZ

Still plenty of runway. So must you worry at all for 5000-feet-plus? Technically, you’re just following the regs. Under §91.103, Preflight Action, “Each pilot in command shall, before beginning a flight, become familiar with all available information concerning that flight.” This includes “runway lengths at airports of intended use” and “takeoff

and landing distance data.”

The reg continues with “aircraft performance under expected values of airport elevation and runway slope, aircraft gross weight, and wind and temperature.” You’ve got that covered, mostly. Runway 21 shows a 0.5-percent uphill slope, favorable for landing, but no performance numbers in the manual to account for that, hence a rounded-up estimate is what you have.

Now, with another 30 minutes to KCDR, check weather and consider the landing. It’s 400-2, winds from the west picking up to 10 knots, gusting to 18. You’re supposed to land in the touchdown zone, right? Does the landing

calculation ensure that? The answer to both: Depends.

The TDZ is defined in the Pilot/ Controller Glossary as: “The first 3,000 feet of the runway beginning at the threshold.” Advisory Circular 91-79A’s definition, which refers to airman test standards, defines it more broadly: “a point 500-3,000 ft beyond the runway threshold not to exceed the first onethird of the runway.” By default we’re

should land on the first third of any runway. However, it’s not a hard and fast reg when flying under 14 CFR Part 91. It’s for Part 121/135 flights, which must land in the TDZ (see §91.175 (c)(1).) And it’s a good idea for all of us.

There’s more “available information” here, too. Runway 21 has a 4-light VASI defining the three-degree glidepath and a TDZE of 3286 feet. Using the AIM’s runway categories, it’s a ‘non-precision’ runway so it will have the centerline and for distance information the aiming point is indicated by two white blocks 1000 feet past the threshold. So apply the first-third rule, 5500/3=1833 feet. That’s not much more than 1500 feet. Still no concerns, but to avoid the discomfort (and higher risk) of landing looking at this as a 5500-foot cakewalk.

Everything goes as planned thanks to a thorough briefing of the markings for Runways 21 and 3 that comes in handy in that 1500 feet. Just before AXOYY, it’s gear and one notch of flaps down. Runway lights in sight, but in a lot of haze a mile out, so you continue on the glidepath. At DA, you clearly see the numbers and VASI, but with the rough air and varying crosswinds, you’ve still got 100 knots/115 MPH on the airspeed, with power, and 25 degrees of flaps. You elect to keep that rather than full 40 degrees of flaps. Now the touchdown zone seems tighter than it did a hundred miles back.

How would you know if the first 1800 feet of runway have passed? The aiming point already went by and you’re still trying to flare. Aha: Runway 3 is a precision runway, which means it’ll have TDZ markings. After the 1000- foot aiming point, there are 2-stripe TDZ markings at the 1500 and 2000- foot points. So when you finally get the wheels down and see that you’ve stopped a few hundred feet from TDZ stripes, you know there’s probably less than 3000 feet of runway behind you. Not super-precise, but something to go on. If the TDZ stripes had gone by before landing, you’d know for sure to go around.

It often takes just one challenging condition to make a flight leave the normal envelope. In those cases, it might take just one little-used piece of information to make things work out. This time, you’ve used it to ensure a safe arrival, if not all that comfortable—but that’s another story.