When thinking about mountain airp, states like Wyoming and Colorado come to mind. But there are plenty of mountainous destinations outside the Rockies. Head 1400 miles southeast, where the Blue Ridge Mountains offer breathtaking landscapes and lots to do in the great outdoors. While on a much smaller scale than out West, these landforms do have enough topography to require some extra planning. Oh, and bring a good GPS.

Cool, an LP IAP

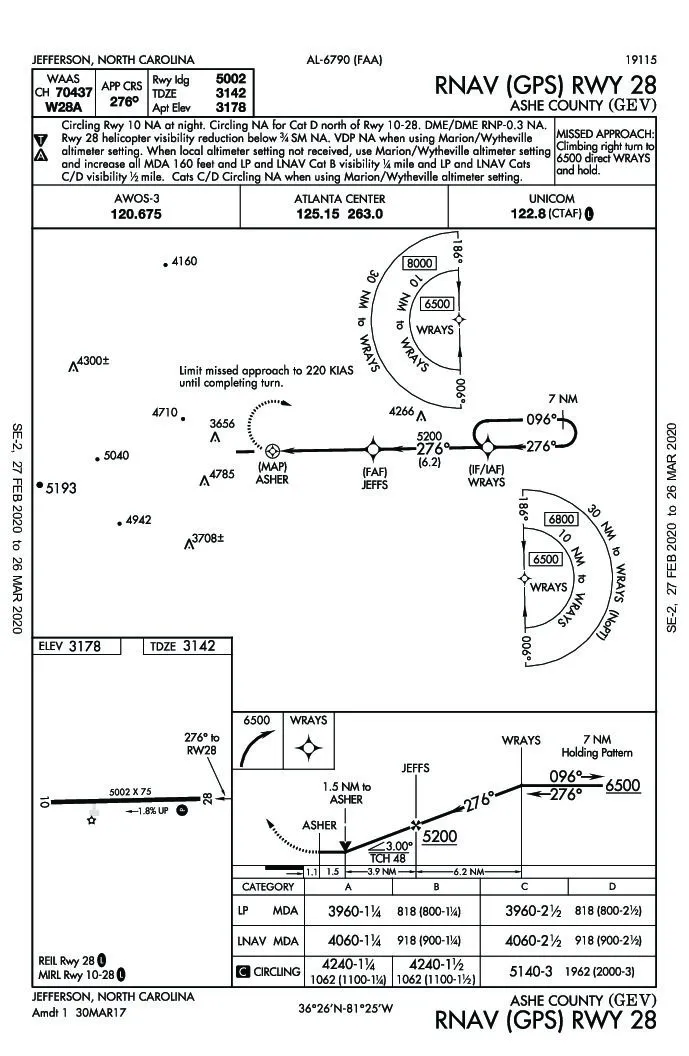

Ashe County Airport (KGEV) near Jefferson is a great destination nestled in western North Carolina. Runway 10/28 sits at an elevation of 3178 feet. That’s the first cue we’re dealing with significant terrain. The second is that there are no approaches to Runway 10. Runway 28 has both an RNAV and LOC approach and they both offer circling, but with southwest winds and the hills it’s probably best to take the straight in.

We’ll choose the RNAV 28 with both LP mins of 3960-1. and LNAV at 4060- 1.. Before we automatically pick the lower minimums, it’d be good to know the differences.

The LP is the little brother of the LPV; it also stands for Localizer Performance but without the vertical guidance. Now popping up in greater numbers, the LP is a non-precision approach with angular deviation (increasing course sensitivity) on final, just like a LOC.

That’s the main difference compared to LNAV (Lateral Navigation), which has linear deviation (constant needle sensitivity) on the final segment. So the LPs can offer lower MDAs than LNAV, 100 feet lower here, made possible by your nifty WAAS-enabled GPS. (For more on LP, see January 2014 IFR, “Approach Secrets.”)

The third cue you’re heading for higher ground is the missed approach point, ASHER, 1.1 NM from the runway threshold. (The LOC uses ESUGY at 1.3 NM.) Why’s so far? Going missed requires the extra space. Considering the airport remarks in the Chart Supplement (not shown), “Rising terrain all quadrants,” the missed instructions on the RNAV are “Climbing right turn to 6500 direct WRAYS and hold.” It’s a 2540-foot climb from MDA to avoid area obstacles as high as 4785 feet, plus a nice big one 10 miles west at 5193 feet.

Officially Mountainous?

With the approach properly vetted, let’s back up to the feeder. We’re arriving from 90 minutes north, Mid-Ohio Valley Regional in Parkersburg, WV, (KPKB with a comfy elevation of 859 feet) and its nearby VORTAC to grab V115 to HVQ at Charleston, WV, then V133 to STOVE, 20 miles north of KGEV.

That fix is right about at the peak of the terrain surrounding Ashe County; note that the stepdowns start way out—30 NM from the initial fix (WRAYS) via the Terminal Arrival Area (TAA).

The what? Oh yeah, these are the circles (often concentric circles) depicted on many RNAV planviews. They take the place of the MSA circle on ground-based approaches, but are used somewhat differently. TAAs aren’t there just for emergency use like MSAs; they are, to quote the FAA Instrument Procedures Handbook, “operationally usable altitudes.” Use the piece of the TAA you’ll fly into as your minimum altitude (unless ATC assigns you one). So, if you’re cleared for the approach without explicit altitude restrictions, once within the TAA, you can descend to the altitudes shown.

The IPH goes on to say: “These altitudes provide at least 1000 feet of obstacle clearance, and more in mountainous areas.” Even those of us from the flatlands know that charted altitudes in “mountainous areas” provide 2000 feet of clearance over the terrain, but our awareness of where those places are gets hazy. There are the obvious spots, like Jackson Hole, Wyoming and the infamous Leadville, Colorado airports. Back east, the Alleghenies and Appalachians certainly qualify (along with their subranges such as Blue Ridge). Ashe County? Sure, it’s right in the middle of the tan-colored topo grading on the VFR chart; the label “BLUE RIDGE MOUNTAINS” could be another hint. But otherwise, how do you know if a given airport’s in a “mountainous area?”

Research takes us to AIM 5-6-16 and Åò 95.13, “Eastern United States Mountainous Areas.” The AIM includes a U.S. map overlaid with, oddly, Designated Mountainous Areas and Air Defense Identification Zone Boundaries. The more obscure Part 95 includes blocks of numerous lat-longs defining those areas. This is far from user-friendly, so we can find better information on the VFR chart. It’ll have the terrain/contour depictions mentioned earlier, and Maximum Elevation Figures showing the highest obstacle in each quadrant. Compare the numbers around KGEV with the corresponding low-altitude IFR chart; there’s an OROCA of 8400 feet, an airway MEA of 8500 feet to the south— well more than 2000 feet over surrounding airports and obstacles.

HILPT or No?

For Ashe County, the 10-to-30-mile TAA rings show 8000 feet on the west side, 6800 on the east. Which one’s yours? The IPH says: “The pilot can determine which area of the TAA the aircraft will enter by determining the magnetic bearing of the aircraft TO the fix labeled IF/IAF. The bearing should then be compared to the published lateral boundary bearings that define the TAA areas.”

Um, okay. While your magnetic heading to fly will be 190 degrees due to wind correction, the magnetic bearing of 173 means the flight path will be in the TAA segment requiring 8000 feet. Higher’s safer anyway, and when within 10 miles of WRAYS it’s an easy enough descent to 6500 feet.

After all that, you still have a procedural question to address: Will you fly the hold-in-lieu-of-procedure-turn (HILPT) or get cleared from WRAYS for a straight-in? For reference, AIM 5-4-6, Approach Clearance, says the HILPT applies when not vectored, not cleared for a straight-in approach, or when there isn’t a “no PT” note on the chart. There’s no such wording on this approach and no other IAFs forming the “T Design” present on many other IAPs. However, the TAA depicts a 186-degree line intercepting WRAYS, 90 degrees from the final course. Your intercept angle will definitely be past 90 degrees, so it’s a parallel entry to the HILPT. Unless, of course, you get vectors in advance and shift your arrival more to the northeast. Barring that, do the hold.

The next consideration is whether you can intercept the inbound during the parallel turn inside the racetrack and continue the straight-in from there? Sure, as long as you do a decent job of the parallel entry (staying within the racetrack path on the holding side, intercepting the final course with normal standard-rate turns, etc.). The AIM backs you up on this: “The holding pattern maneuver is completed when the aircraft is established on the inbound course after executing the appropriate entry. If cleared for the approach prior to returning to the holding fix, and the aircraft is at the prescribed altitude, additional circuits of the holding pattern are not necessary nor expected by ATC. If pilots elect to make additional circuits to lose excessive altitude or to become better established on course, it is their responsibility to so advise ATC…”

After sorting out the TAA, the LP approach, the “rising terrain” at the destination, and the HILPT, you decide to tighten things up on the missed approach. That’ll be a climbing right turn to 6500 feet (about 2500 feet above the MDA) to WRAYS. To be extra safe, let’s plan to go missed, if need be, 1.5 miles before ASHER, at the visual descent point, with a rounded-off MDA of 4000 feet. This will make things plenty comfortable given the new territory. Good thing the weather’s not all that bad there, 1800 feet and 6 miles, but it does require an alternate—Hickory Regional, NC, less than 30 minutes to the south of Ashe County. It’s a Class D with a TAF, multiple ILS approaches, lower terrain, and it’s VFR. We’ll also check weather when over Charleston to decide whether to continue, then check again just before flying across the mountains.

It’s a lot to digest, but a good review of LP approaches, TAAs, HILPT, plus some answers to stuff you’ve always wondered about mountainous areas. Sure sounds like a cool destination … New River canoeing, anyone?

These plate articles are very sophomoric in nature. Can you not come up with something more complex?