The old HBO series Deadwood told the tale of a lawless town where the rules were what you made them. Our aviation version is the Wild West town of FAR 91.3 (b): “In an in-flight emergency requiring immediate action, the pilot in command may deviate from any rule of this part to the extent required to meet that emergency.”

Welcome to Deadstick, the place where losing an engine in IMC grants you the authority to ignore those pesky course reversals, crossing altitudes, and ATC instructions. This plane is coming down and the only one who can make that happen on a runway is you. Welcome to what’ll probably be the only sim challenge that doesn’t contain a single missed approach.

The Rehearsal

Get ready to star in this adventure by positioning your aircraft on Runway 24 at Muskegon County (KMKG) in Michigan. Pick whatever aircraft best resembles an aircraft you fly. If you have the option for retractable gear, you might want to use it as that adds a variable to this exercise and makes it more, um, fun. But the choice of the airplane is really up to you. If you fly a twin, slum it for this sim challenge and go back to the high-performance single you probably traded in for your first twin.

You will want some kind of a GPS with a moving map. That could be as simple as an iPad linked to your sim, or it could be in the sim. Even the old portable GPS option you get with creaking copies of Microsoft’s FSX will do the trick, although it is a bit harder. Multiple GPS units are allowed so long as you don’t complain they disagree. You know the old saw about the man with two watches never knowing the time.

Set the wind to calm from the ground to the stratosphere, the ceiling to 200 overcast with tops at least 10,000 feet, and the visibility to one mile.

Depart Runway 24 straight out with instructions to climb on runway heading to 3000 feet then direct Muskegon VOR (MKG). Continue your climb to 9000 and hold as published over the VOR. If you reach the VOR before reaching 9000, climb in the hold. I said there’d be no missed approaches. I didn’t say anything about departures.

Once you’re in the hold at 9000 and cross MKG inbound—pause the sim. Now, if your sim allows, save this situation. You’ll be coming back here several times. It’ll be like another movie: Groundhog Day, where you fly, maybe die, and then reset to try again.

Once the situation is saved, resume the sim—and pull the mixture to idle cut off. You’re 8.4 NM from the airport dead ahead. If you don’t want “dead” to preface even more things today, you have to land there. (OK, it is pretty flat around Muskegon, so landing in a field would probably also work. But let’s try for pavement.) Head straight for the airport using your GPS and maneuver to land on any runway.

Maybe that worked out perfectly; maybe it was … educational. Either way, reload the situation where you’re at 9000 feet over the VOR and review a couple charts.

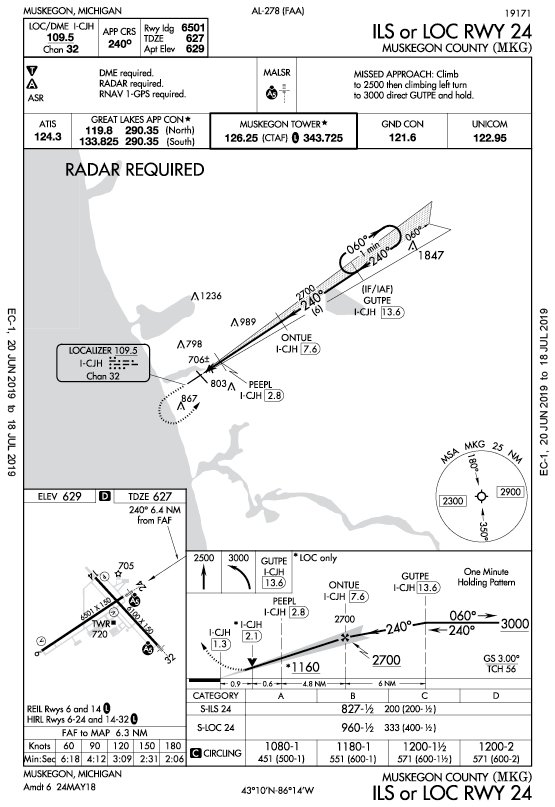

The VOR is almost perfectly between two ILS approaches, the one for Runway 24 and the one for Runway 32. Pick one and unpause the sim. Now dial up the localizer you’ve decided to use in your number one nav and fly it. No, not as charted, course reversal and all. You’re deadstick. Join the localizer any way you see fit in this emergency and use its guidance to reach the runway and land.

Your 15 Minutes of Fame

Put yourself back on Runway 24 with a working engine. Keep the ceilings and visibility the same, but dial up a surface wind of 190 at 15 knots. If your sim lets you specify a different wind aloft make it 200 at 30.

Now launch with the same plan and climb to the published hold at the VOR. Once you’re at 9000 and cross the VOR inbound … pull the mixture to idle cut off and decide: Which method will you use to get back to Muskegon, ILS or spiral down? How will you do it given these winds? Don’t look at me for answers. Not until you get to the next page, anyway.

Make your choice and make it work. If it doesn’t, relaunch and try again. If it does, pick a different option and see how that works out.

Questioning Yourself

Now that you’ve tried this—you have, haven’t you?—here are a few points to consider.

1. How did you hold at MKG? How would you use a GPS?

2. What speed did you use for gliding to KMSG on the first attempt? What speed did you use for landing?

3. Which runway did you aim for on that first attempt and why? What was your technique to align on final in a position to land?

4. For the practice ILS, where did you intercept the localizer and why?

5. If you’re successful flying this ILS, when will you see the glideslope center?

6. When gliding into a headwind, what speed do you fly?

7. If you went straight for the airport with the winds, which runway did you use?

8. If you followed an ILS in the windy scenario, which approach did you use?

9. On the ILS with the wind, what could you use as a how-goes-it to see if you’ll reach DA-ish about the time you’re on short final?

10. If you were in this situation for real, Muskegon would be a great place because you’d get a bonus option for the approach. What is that option?

Bonus: The ILS or Loc Rwy 24 and 32 have similar requirements. Both require radar for transition from the en-route structure. Both require some combination of radar, DME, and GPS for the approach and missed. But the Runway 32 approach requires “Radar or DME, and GPS,” while the Runway 24 approach requires “Radar and DME and GPS.” Why?

Break a Leg

Hopefully this practice yielded at least one landing that happened on the intended runway. Or something close enough to walk away from. At the time of this writing Muskegon had a NOTAM that Runway 24-6 was closed. Imagine completing this challenge for real only to break out at 200 feet staring at an X-shaped barricade. Would you pull the heroic attempt to sidestep and land on the taxiway, or just crash right through it to find the runway beyond?

Maybe a bit of crashing would actually be a benefit. I was recently regaled with the story of a Bonanza pilot who suffered a crankshaft failure at altitude and glided down to a perfect, on-airport landing. He even had enough energy in the bank on rollout to clear the runway and stop politely on a taxiway. Nothing but the oil slowly pooling into a hazmat event beneath his cowling looked the least bit out of place.

And that was too bad, because that means it wasn’t an accident and there was no claim to make on his insurance. He was on the hook for the entire $50,000 engine replacement. Had he done any damage at all—dinged the prop, tore off a gear door, broken a nav light on a runway sign—he could have made a claim that would have covered the entire event, including the engine that failed.

Lesson learned: Sometimes you want to be a bit less than perfect. Or at least you want to kick the rudder to clip a runway light as you roll to a stop.

Jeff Van West usually makes a clever, self-deprecating remark here, but this time he’ll relate a true tale. When first launching to fly this challenge, he started on the ramp and taxied out, but skipped the run-up as he often does. He did, however, check power and engine instruments on the takeoff roll—and rejected the takeoff. For some reason the Cardinal was producing partial power. Nothing was wrong in the configuration and reloading the aircraft fixed it. But it was a real example of checking items on the takeoff roll before launching into (even virtual) IMC with a sick bird.

Possible Answers

1. This hold is depicted on the en-route chart as part of V450—R-095 inbound, right turns. If you were direct MKG with the GPS, you’d better switch it to OBS mode or inbound on a course of 275. Or just program the hold if your navigator permits.

2. Published best glide is at gross weight. If you’re lighter, the best glide speed is a bit slower for most GA aircraft. The landing probably depends on how high you are on final approach. If you’re high and have energy to spare, you can fly faster than best glide, enter the landing flare, and bleed off energy in the flare for a soft touchdown. If you need maximum distance, you should probably transition from best glide at 200 feet AGL or so, to minimum sink. That’s the lowest rate of descent and the softest impact (vertically). That’s usually about halfway between Vbg and Vs .

3. Runways 24 and 32 offer approach lights that’ll be a big help in alignment as you turn onto whatever final you can muster. A useful technique for that turn is aiming for a “high key,” which is like a downwind position abeam the numbers, but about 1500 feet above the touchdown zone. If you can maneuver to cross through high key, that sets you up to make a descending, 180-turn to “low key.” That’s usually short, short final and about 200 feet AGL. Pass through low key basically configured for landing and you might walk away unscathed. As an aside, did you try to follow a vacuum heading indicator to get there? Not much vacuum from the dead engine…

4. It’s helpful to know your glide ratio as an angle using the 60:1 rule. A 60:1 ratio is about one degree. If you have an 8:1 glide ratio, that’s about a 7.5-degree (60/8) glide angle. The ILS for Runway 24 has a 3-degree glideslope from 2700 at ONTUE to a threshold crossing height of 56 feet. Descending at 7.5 degrees would require starting 2.5 times as high, which means crossing ONTUE inbound at 6750 or higher. Otherwise you’d better join that localizer inside of ONTUE to even have a chance.

5. Per the answer just above: Right about the time you land. If the three-degree glideslope centers before you see runway, you’re too low. Make other plans.

6. Glider pilots often face this conundrum. One hack is to add at least half or even all of the headwind component to the glide speed. Best glide is the greatest distance over the ground for altitude lost. But descent rate increases slowly above best glide. In a headwind, the best ratio for distance is faster than best glide. Sometimes much faster. Since there’s no time for fancy math, use the hack of half the headwind.

7. Heading for the center of the field is a good start. From there, it depends on your altitude, but Runway 24 is probably the best choice, using a position upwind of the threshold to spiral. That gives you a tailwind from high key to low key. Also plan a high key and low key such that you’ll reach low key already over the runway rather than on short final. You have a headwind and there’s plenty of pavement to overshoot and still land. There’s no pavement if the winds make you come up short.

8. If following the ILS was the plan, we’d head into the wind toward Runway 32. More altitude would be lost maneuvering to join the localizer, but once on it the tailwind would help make reaching the runway easier. Keep target altitudes on the way down as progress checks. It’s easy to increase rate of descent or even slip on the localizer, but there’s little way to stretch it if you realize you’re not going to make it.

9. Once you’re established, compare ETE to the runway with your vertical speed. If you have 2000 feet above the airport elevation, are two minutes from the runway, and are descending 1000 feet per minute, you’ll make it with just a bit to spare.

10. Muskegon Approach offers Airport Surveillance Radar approaches (ASR) as noted on the approach charts below the non-standard takeoff and alternate minimums.

Bonus: [I’m actually not sure. I think it’s a charting error on the 24 approach and I’m waiting for the answer. The Runway 32 is correct in that DME or Radar is required for the localizer approach to identify the stepdowns and the MAP. GPS is required for the missed approach. I don’t see why Radar is required at all for the Runway 24 once you’re established on the approach.]