Rime ice giving your Cessna 210 a quarter-inch coating was the inbound surprise to Mission Field in Livingston, Montana. As one accustomed to life without ice protection, you were careful in the planning and had an alternate, but you simply didn’t expect to pick up that much extra drag on approach. Still, cloud levels were as forecast, with just a 3000-foot layer to dive through on descent. This helped in the end, along with arriving 15 knots faster, clean, with extra power, then going gear-down later on final, just to be sure. Luckily, conditions at KLVM were expected to improve in a couple days for departure back east to Alexandria, Minnesota. Yeah, the forecast…

Fly the Numbers

Launch day dawns to a ceiling of 800 feet, freezing temperature, with a 4000- foot layer to climb through. It should work out ice-free as the nearest AIRMET Zulu begins 60 miles east and reaches 100 miles slightly north of your route, covering altitudes between 6000 and 10,000 feet. Naturally, icing conditions could be more or less widespread than that, but you’ll stick to the plan for now given tops around 7500 feet and gradually clearing skies. An easy escape plan from icy IMC would be to the south.

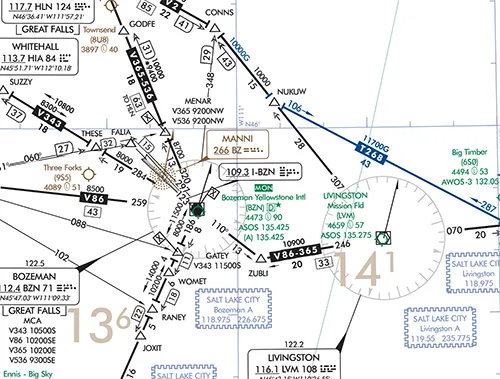

Departure from Runway 22 will be into a typical 20-knot wind that’ll hold steady on the initial climb. By the time you turn eastbound and break out of the clouds, a 50-knot tailwind will scoot you down V2 to the Jamestown VOR, then direct to KAXN. In fact, you plan on a 70-knot groundspeed gain at 11,000 feet to make it non-stop in 3. hours.

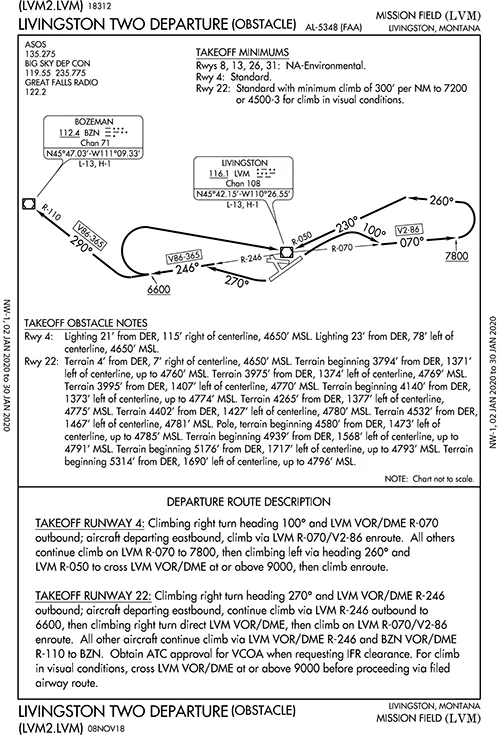

Before that, though, keep the focus on any fine print for the departure. For Runway 4/22: “Use Livingston Departure.” On to the procedure list. The LVM2.LVM on first glance looks like a propeller-shaped path around the airport that doesn’t go anywhere except back over the LVM VOR/DME at the field. (When there are multiple turns or some complexity to an ODP, there’ll be both textual and graphical instructions, as in this case). So after takeoff, go west at first to pick up R-246 from the navaid. For those eastbound, there are additional instructions to continue climb to 6600 feet before taking a right turn back to LVM for R-070/V2-86. Thereafter, the MEA is 9700 feet en route to the Billings VOR.

More fine print: Runway 22 takeoff minimums are “standard with minimum climb of 300’ per NM to 7200 or 4500-3 for visual conditions.” The 210, laden with full fuel and cargo, will be climbing from 5000 feet pressure altitude at zero C. The POH shows about 633 fpm at 94 KIAS, all things being equal on the climb power, etc. Now, the climb goes to about 8000 feet pressure altitude, and so the rate of climb per the table tapers off to 460 fpm. At 94 knots, you’d need a climb rate of 470 fpm to achieve 300 feet per NM—pretty close to what the ODP calls for.

Keep in mind this would be the case on that mythical no-wind day. In reality, the slower groundspeeds will be in your favor—initially. A groundspeed of 74 knots will require a 370 fpm; 64 knots, 320 fpm, giving you a comfortable performance margin. Meanwhile, the time-fuel-distance to climb table, interpolating for a climb from 5000 to 8000 feet PA, shows six minutes and nine miles. While reviewing the en route chart, you note that the ODP’s 6600-foot turning point happens to take place at ZUBLI, which isn’t included on the ODP sketch. But it’s a fix on the associated airway—an excellent observation that’ll come in handy.

A Big Workaround

That’s an awful lot of pencil time to come up with user-friendly VSI numbers, so how did the FAA come up with 300 feet/NM for this anyway? The Instrument Procedures Handbook gives some background: “All departure procedures are initially assessed for obstacle clearance based on a 40:1 Obstacle Clearance Surface (OCS). If no obstacles penetrate this 40:1 OCS, the standard 200 FPNM climb gradient provides a minimum of 48 FPNM of clearance above objects that do not penetrate the slope.” If not, there are workarounds. We’ve all seen increased weather minimums for departure or an ODP with a prescribed climb rate, flight path or, as with KLVM, both.

Numbers in hand, you depart, confident the 210 will reach 6600 feet at the proper place before turning eastbound per the ODP. There, the groundspeed shoots up to 124 knots, making the required climb rate 620 fpm. That’s still a decent margin for the Cessna. In fact, the takeoff goes as calculated and the VSI reads 700 fpm. Looks like it’ll work out OK—just. You’ve done the due diligence and figured the route, speeds, climb performance and converted the numbers to feet-per-minute for monitoring. Now it pays off.

That is, until entering IMC. The carefully planned climb has turned into a seat-of-the-pants conundrum. Rime ice builds on the wings and windshield at a startlingly fast rate. The VSI drops to 500 fpm, 400 … to prevent a stall, you flatten out the climb and by the time the altimeter reads 5200 feet, it’s down to 200 fpm. Having lost sight of the airport and surrounding terrain, the only choice is to, well, fly the airplane. Oh, and hang on to that ODP. You’re darn glad to have noticed ZUBLI on the en route chart and even thought to plug it into the GPS on the ground for extra situational awareness. While only up to 6300 feet when you reach the fix, you’re going to have to make that right turn and stay over the airport, the best place to be in any urgent situation.

Refigure on the Fly

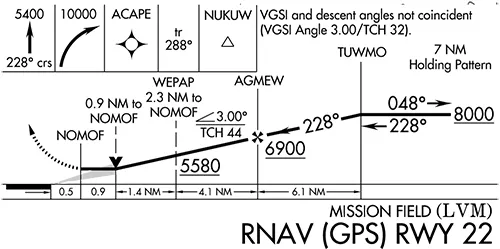

At this point you must consider the worst. If the ice gets heavy enough to force a descent, an emergency approach back to the airport below is the only option. Under Åò91.3, you’ll use whatever’s at hand to make it back to the runway. With a working GPS and RNAV 22 approach activated, the goal would be to see if the descent rate allows you to aim for WEPAP (2.8-mile final) and reach it at about 6500 feet—a thick margin above the prescribed 5580 feet. You should break out of the icing and clouds around 5500 feet at NOMOF, the last stepdown fix 0.5 NM from the runway. Then, still clean, aim to stay a couple hundred feet above the LNAV MDA of 5360 to ensure you’ll make the 5700-foot runway.

The easy part would be adding all that available drag to finish with a steep but visual descent to land. If you’re halfway down the runway, fine. There’s no time to calculate a desired sink rate, but you know that using that into-the-wind groundspeed of 74 knots on the standard three-degree glidepath will be at about 400 feet/minute. Now, you’ll want at least 700 feet/minute. That could be as much as a five-degree descent, but who cares about that now?

The instant the needle swings at LVM, you turn right to 270 degrees. The GPS, zoomed in, confirms you’re where you think you are. How many minutes of this will it take to reach 7200 feet? You are now at 6400 feet; it’ll be four more minutes—if you can maintain 200 fpm.

You’d sure like to report all this to ATC, but there’s no answer. The ice could be interfering with the antenna and you’re not sure if there’s a transmission. You know that if you lose VHF navigation, you have RNAV as backup (barring any GPS signal issues). But what is the plan for a comm failure on this ODP? In reality, you just carry on—ATC will keep the airspace clear until establishing communications and confirming your position and flight path. If a NORDO situation is suspected, it’s a matter of flying the clearance (the ODP to 7200, then V2 eastbound), even if you fly an extra lap over the airport. At any rate, you’ve decided you are indeed under Åò91.3’s emergency authority and your job is to keep flying the airplane. Now at 7000, NW-1, 02 JAN 2020 to 30 JAN 2020 NW-1, 02 JAN 2020 to 30 JAN 2020 the clouds start to break up, and there’ll soon be tops, clean wings, and ATC contact. Blue never looked so good.

Nice article and good food for thought. Freezing temps and visible moisture, expect ice. However, your numbers are somewhat inconsistent. In the section FLY THE NUMBERS, you say the ceiling in 800 ft. with a 4000 ft layer to climb through. From the sectional, airport elevation is 4659 MSL. The 800 ft ceiling puts the bases at 5459 MSL. The 4000 ft layer puts the tops at 9459. You then say “…but you’ll stick to the plan for now given tops around 7500 feet.” That doesn’t jive with the numbers you presented a few lines earlier.

Regardless, it’s still good food for thought, and your methodology for thinking through the problem is excellent. I would only add a check on the winds aloft forecast. With freezing at the surface, a temperature inversion would be a nice thing to have, and the winds aloft would tell you if you should expect that.

Unless the FAA moved ZUBLI intersection 13 nm west since this article was originally published, I believe any reference to using it for situational awareness on flying this ODP is dangerous and misleading. The current enroute chart shows ZUBLI intersection is 20 nm to the southwest of LVM along V86-365—just over the Bozeman Pass—which has a tower up to 6930’ MSL located just beyond. The ODP’s “6600-foot turning point” should be WELL PRIOR to ZUBLI or a CFIT accident is highly probable—which I believe is why ZUBLI is not included as part of the ODP text or graphic. The minimum climb gradient required by the ODP for the departure off of RWY 22 is 300 ft/nm, which would ensure a climb through 6600’ MSL by 6.5 nm west of the field, well short of the 20 NM distance to ZUBLI.