Maybe You Shouldnt Do that

I once undertook a ferry flight that was, well, dumb. Similarly, a type-specific magazine I get recently ran a true-confessions story by a pilot who, in the clarity of hindsight, probably should have missed, not landed.Most of us accomplished pilots (as the masthead says) can do far more in an airplane than we should. What does that mean? Well, I mean we probably could, for example, safely fly an airplane that isnt quite airworthy or perhaps we could complete an approach to a landing using abnormal maneuvers and live to tell (or brag) about it later.

A Tale of Two Pilots

Pilots retiring from professional flying and downsizing into personal aircraft often want to fly something thats capable, yet simple and efficient. Thats understandable, as they want to use their extensive experience. Theyre also flying for themselves (and paying for it), so an airplane that economically delivers practicality and enjoyment is the goal. The following examples reflect the common downsizing profiles Ive seen.

So, Your New Ride is Smaller

Shrinking size, horsepower and number of engines requires big adjustments as you ease into the life of a light-airplane pilot. But smaller and simpler still requires proper transition training.

Down-Transitions

Many of our ranks are professional pilots because they simply love to fly. They find a way to fly no matter what. For them, retiring from a career in aviation simply means they no longer get paid to fly, but theyll find a new ride. These are usually superb pilots-pilots pilots-but they can sometimes struggle when transitioning from a magic carpet with dual FMS, dual radar, dual engines, surplus power, autothrottles…and redundant redundancy. Of course, there are also many owner-operator pilots who fly sophisticated aircraft ranging from bizjets to piston twins who similarly find themselves looking for a new way to sustain that aviation fix as they retire.

Briefing: July 2015

More than 4400 comments were filed in response to the FAAs proposed rule for allowing small unmanned aircraft into the national airspace system, and the general aviation advocacy groups had their say. EAA, AOPA, and the General Aviation Manufacturers Association all said the FAA should lower the ceiling for small UAS operations to 400 feet, instead of the proposed 500 feet, to provide a bigger buffer between UAS and manned aircraft. Other suggestions included requiring UAS to automatically terminate flight if communications are lost, and ensuring that the operators of manned aircraft arent required to add new equipment as a result of UAS integration. The FAA will now review the comments before publishing a final rule, which is expected to take up to 18 months.

Readback: June 2015

I read your editorial The Drones Are Here with interest. You asked the question When was the last time you flew below 400 feet away from an airport? My answer is: yesterday.As a seaplane pilot, I do this all the time over bodies of water. So do thousands of other seaplane and helicopter pilots. There is no way on earth that we would ever be able to see and avoid these tiny toy aircraft-at least not in time for the avoid part-and for sure, their untrained operators would not be likely to anticipate and avoid us. It is not a matter of if, but when someone will be killed by these dangerous drone operations. I guess our lives are less important than the interests of hundreds of thousands of drone hobbyists.

Readback: May 2015

Rick Durdens December 2014 complex article about tailplane icing was well researched and well written. It also proved prophetic.At Cincinnati Municipal while my L-39 was being fueled, Bill Rieke, an icing researcher, came over to chat. He said that he thought the L-39 would be particularly susceptible to tailplane icing and stall because of the smallness of tailplane, the thinness of the airfoil and the need for ventral VGs.

Do You Know Ice?

Februarys Cowboy and Cowards sparked some passionate responses about known icing and my assertion that known icing is observed icing. To better understand known icing, we need to look at the concept from definitional, legal, and safety perspectives.

More Than a Currency Flight

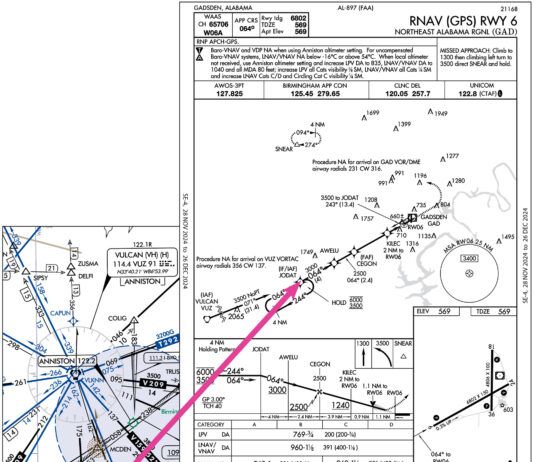

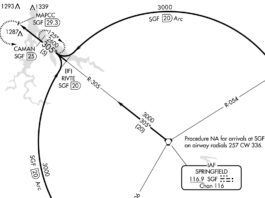

As a CFII, I do plenty of recurrency training for instrument flyers as a safety pilot and coach and as an instructor conducting an IPC. I like to use the IPC content as a starting point. Heres a typical example:

Embrace The IPC

Many of us feel that an IPC is as much fun as a visit to the dentist. We go through the checkup and if things are OK, we go on with our lives til the next appointment. Worse, for some the IPC is akin to a root canal-something to dread because theyve neglected the preventive care. Its the penalty for losing currency past the six-month window specified in 14 CFR 61.57.In any case, IPCs dont pique much excitement. They are an occasional formality for those who fly the system often, or a major chore for those who dont. It doesnt have to be that way. Rather than something to avoid, an IPC can improve your skills while you brush up on procedures you dont use often. You can even go further and have a bit of fun.Yeah, fun. In daily IFR flight, predictable and comfortable are good. The best response to How was your flight? is Uneventfully successful. We dont want unusual or difficult. Actual equipment breakdowns or emergencies are thankfully rare, but you want to be on your game when they happen. Unfortunately, all that routine doesnt keep you on your game for the abnormal situations.Use the IPC to stretch your skills. Figure out what youve neglected and refresh those basics. Then tackle new things. This keeps you proficient while you continue to expand your IFR repertoir. As a bonus, youll never worry about staying current.

To Log or Not to Log

Youre in the muck on your hometown localizer approach at 3000 feet. You intercept final, center the needle and catch a glimpse of the highway below. A mile from the FAF and seven miles from the runway, still at 3000 feet, you begin to make out the runway. With visibility only three miles, you wait until crossing the FAF before descending to land. Can you log that?

Briefing: June 2010

Efforts from companies like Swift Fuel and GAMI to find a replacement for 100LL may get some more serious attention now that the EPA has released its advance notice of proposed rulemaking regarding the need to eliminate lead from fuel. Converting in-use aircraft/engines to operate on unleaded aviation gasoline would be a significant logistical challenge, and in some cases a technical challenge as well, the EPA said. The EPA also acknowledged that a joint effort with the FAA will be critical and has not set a date for the rulemaking, but said it would like to see leaded fuel phased out as early as 2017.