First we got an e-mail from a reader concerned that Garmin was removing airports with runways under 4000 feet from their worldwide database. Next, a reader related a situation where he’d been cleared direct to a fix that wasn’t in his Garmin GNS 430, but it showed up when he loaded an RNAV arrival.

These produced some internal discussions and one of our staff related a story from a friend of his who’d busted a stepdown fix altitude because the stepdown fix wasn’t depicted on the approach in his Bendix-King KLN-94.

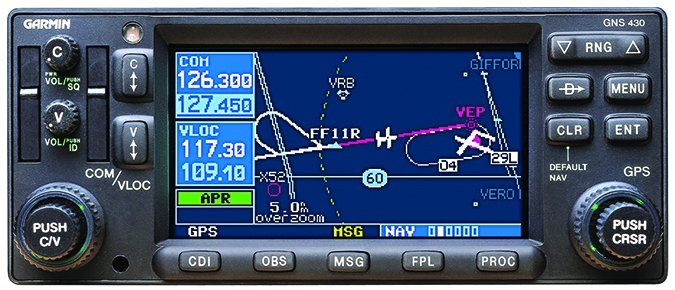

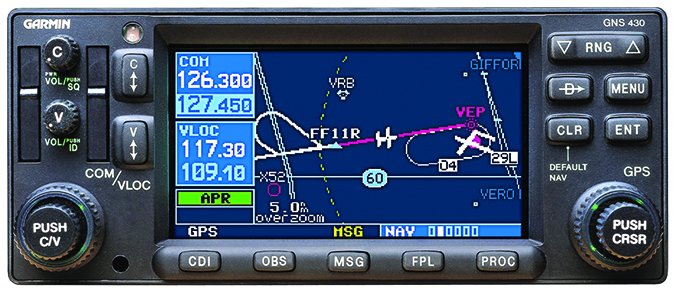

We tend to think of groundbreaking navigators like the KLN 94 and the GNS 430 as high-tech, modern devices. Sure, there are more modern devices out there now, but these helped define the market and the new ones really don’t do much (or anything?) that these originals couldn’t do. But, the reality is that the technological constraints of designs approaching two decades old are showing up more readily in various limitations.

High Tech?

Not convinced? Consider that the original GNS 4xx/5xx was designed using a high-end, fast processor—one from the Intel 386 family. Today you can buy a watch with more processing power, so it’s no wonder these navigators are facing limitations. In fact, one might consider that it’s amazing they’ve had and continue to have the life they do.

Think about the computer you used, say, in 2000. How much memory did it have? Perhaps as much as 64 megabytes? Was the disk bigger than a couple gigabytes?

Compare that with the computer you’re now using. Our tablets even have up to 64 GB of memory and the disks in our desktop computers might have a terabyte or two.

OK, so data storage capabilities have expanded. That’s a good thing, because the data we want to store in our navigators has also exploded. Just look at the sheer number of RNAV (GPS) approaches we have now. Each of those approaches has many fixes.

So, we’re now storing massive amounts of additional data in our navigators without an ability to increase the internal processing power and data storage mechanisms. How’s that working out?

No More Worldwide Data

Not so well, apparently. Earlier this year, Garmin announced that their worldwide database would now be forced to drop airports that only have short runways. The reason is simply that the sheer volume of data required to store every runway, every frequency, and every approach at every airport in the entire world exceeded the capabilities of some of the older navigators. One might be amazed that limitation wasn’t reached long ago.

It’s important to note that this doesn’t affect the regional databases, so those still include all the data. Garmin’s choice to limit the amount of data in the worldwide database makes sense, actually, because chances are that an aircraft that needs worldwide data, with the range to fly in multiple database regions in one trip, probably isn’t too likely to be landing at an airport that doesn’t have a runway over 4000 feet long.

But, even if you are flying your Cirrus around the world, you can still use multiple regional databases to get all the airports you want or need. So, in this case at least, a small problem with big data has an easy solution. That’s not always the case.

Missing Direct-To Waypoints

Recently a reader sent us a note explaining what seemed like a missing waypoint problem with his Garmin GNS 430. ATC had given him direct to a waypoint, but even with a current database and confirmed spelling, the waypoint was nowhere to be found. After a lot of back and forth with ATC, he finally just had to say he was unable to fly direct to that fix; ATC gave him vectors.

On further investigation, the pilot found the fix within an RNAV arrival. He again confirmed the spelling, but his navigator still refused to accept a direct-to that fix name entered into the flight plan. Finally, our pilot added the arrival containing the fix to the flight plan and deleted all the fixes except the one in question. That worked; he was able to go direct to the fix.

Confused by all this, we checked our sources at Garmin and learned some very interesting things. First, they correctly surmised the navigator was an original 430 that had not been updated for WAAS. Next, they pointed out that this is expected behavior and went on to give us the technological explanation of why.

That explanation, we were told, centers on a “consequence of having an older unit in a world of exploding amounts of data.” As we discussed above, there has been a massive increase in the number of intersections since the 430 was designed in the mid-1990s. The internal data structure for fixes eligible for direct-to use in the original 430 is limited to a total of 64K. (That’s computer-speak for 216, or an actual 65,536 give or take a few for overhead.) Those fixes are classified as “enroute.” Back when it was designed, that number provided significant room for future growth.

Raw Jeppesen data categorizes fixes into two groups. They use the same “enroute” designation and all those go into the “enroute” type in the navigator to be eligible for direct-to routing. The other fixes are called “terminal” and are assumed to only be used within approaches, arrivals and departures. Thus, “terminal” intersections wouldn’t normally be thought of as targets of direct-to navigation outside of the terminal procedure.

Further muddying the water is that oftentimes terminal fixes don’t have unique names. The example Garmin provided is that there are 153 different terminal fixes all named “40VOR.” On the other hand, there are many fixes identified by Jeppesen as terminal fixes that might need to be the target of direct-to navigation. Garmin wants to reclassify these terminal fixes as enroute fixes and will do so if the fix meets certain criteria like having an actual name that’s unique within the country.

And that’s where the problem occurs. If Garmin promoted all such terminal fixes to enroute fixes, it would exceed the 64K limitation inside the navigator, thus making all fixes unusable—a very bad thing. Thus, stricter promotion rules have to be used in the database for the original (non-WAAS) GNS 4xx/5xx and older navigators.

Our reader was assigned direct to one of those terminal fixes that is eligible for promotion to an enroute fix using broad rules, but didn’t make the cut for database-size reasons.

We should hasten to point out here that this describes behavior in the pre-WAAS GNS 4xx/5xx navigators and the older GPS 150/155s, but is not an issue with the WAAS GNS 4xx/5xx units, the G1000 or the GTNs, all of which have expanded internal data structures.

Apparently there’s also a bureaucratic option to fix a specific problem. If, indeed, ATC regularly uses one of these terminal fixes as the target of a direct clearance, the airport manager can submit paperwork to get the fix recategorized as an enroute fix so it doesn’t have to compete for promotion.

Missing Stepdowns?

Each of the Bendix/King KLN-series navigators was a ground-breaking unit in its ability to allow general aviation pilots to utilize PBN procedures. Although cutting edge at the time of their release in the late 90s and early 2000s, these navigators remain a bit of a time-capsule of the early days of PBN navigation. They remain effective navigators, but pilots these days may be caught off-guard by limitations on the units due to the inevitable march of technology since their release.

Recently a pilot was flying an RNAV (GPS) practice approach using a KLN 94. Upon passing the final approach fix, the GPS sequenced to the missed approach point rather than the step-down fix shown on the approach chart. The pilot incorrectly assumed that since the fix wasn’t shown on the procedure loaded in the GPS, it wasn’t relevant to what he was flying. So he descended to the final MDA outside of the step-down fix. That earned him a low-altitude alert from ATC.

We spoke with our contact at Bendix/King to get to the bottom of the missing step-down fix and to learn about other limitations the KLN-series of navigators might have. It turns out these navigators were developed to support the early GPS overlay approaches—before RNAV (GPS)-only approaches—which did not feature step-down fixes in the intermediate or final segments.

So the system software does not have the ability to accept the coding for those fixes. It’s critical that when flying behind these navigators, pilots should reference the distance from the MAP (or distance from the FAF when identifying an intermediate step-down fix) to determine when they have crossed the step-down fix.

Another limitation on the KLN-series of navigators that is due to database coding is a lack of support for multiple approaches of the same type to the same runway end. These are the procedures that are published with, for instance, an X, Y, or Z suffix. In cases where there are multiple approaches of the same type, Jeppesen filters the approaches so that the KLN-series database will include the one approach that is “most appropriate to the navigator.” Generally this means the non-RNP approach that can be flown to the lowest minimums without requiring WAAS.

A pilot new to any device should undertake transition training or a thorough review of the manual. Then you should get some buttonology practice on a few VMC flights.

The tricky part on the KLN 94 is that these limitations are not apparent from the manual, and the reason isn’t surprising: The navigator hasn’t changed, the environment has. The manual for the KLN-94 doesn’t discuss these limitations because when it was developed, they weren’t really limitations at the time. It’s only progress that has made them limitations.

Bottom Line

We’ve just become aware of these limitations, but there will almost certainly be more that we’ll trip over in actual use.

These limitations will likely get worse as the total amount of data and procedures continue increasing beyond technology that is a couple decades old. As even modest growth of the airspace system continues, older navigators will require increasingly aggressive limitations in the handling of that data to keep them usable at all. While these limitations initially affect only a few of us, we’re betting that limitations will become more evident and have greater impact. If you have an older navigator, watch out for technological limitations and let us know what you find.