The FAA’s Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge is clear; “Of all the senses, vision is the most important for safe flight.” This statement is particularly true for instrument flying where sight must often overpower conflicting cues from our other senses. Over the years, we’ve likely forgotten the little bit we learned about vision in our initial pilot training. Let’s review the basics of vision and explore what happens as we age. Finally, we’ll look at what happens when vision goes awry at night in IMC.

Anatomy

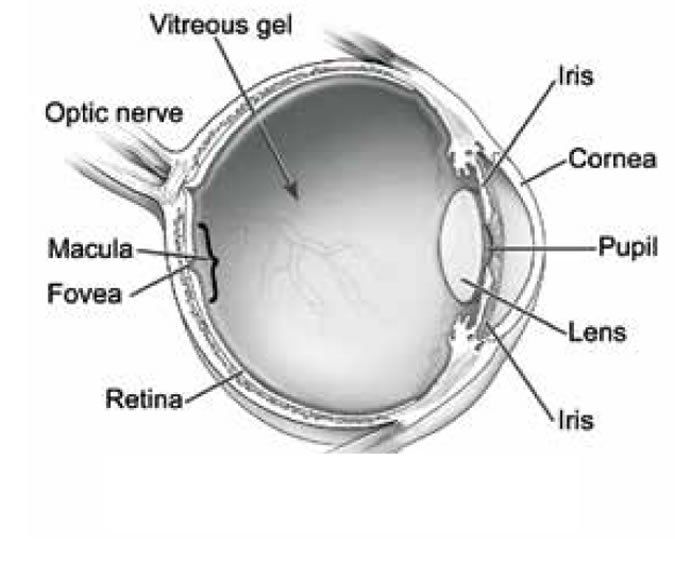

Think of the eye in two parts: the front filtering area and the back receiving area. Light enters through the cornea—a clear five-ply windscreen that protects the parts inside. The pupil then limits the amount of light entering the eye. The diameter of the pupil is controlled by muscles in the colored iris. The lens focuses the light to hit the right area in the back. The space between front and back is filled with a clear fluid called vitreous humor.

The back of the eye is the retina; it is a big baseball glove catching light. The central part, the palm of the glove, is the macula with a high concentration of cones. Within the macula, the fovea is an area with only cones. This is where the lens concentrates light when focusing on an object.

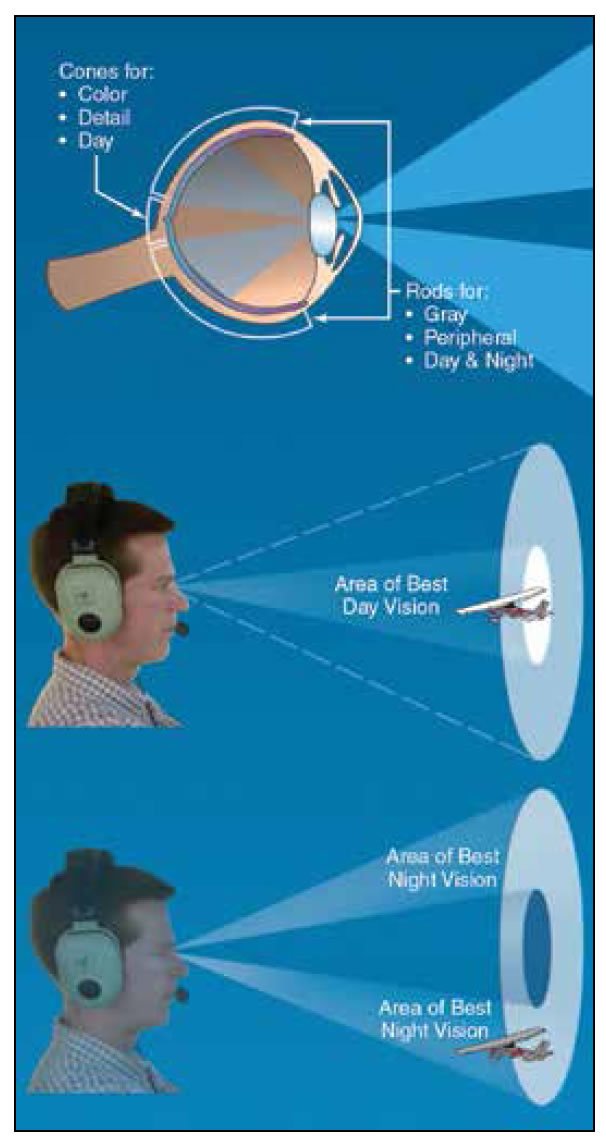

Light hitting the retina is converted into electric signals by cones and rods. Cones are responsible for color vision but require a lot of light. Three types of cones exist, reacting to red, green, and blue light. Rods, conversely, are much more sensitive but cannot discern color. The retina houses 90 million rods around the outer edges and 4.5 million cones amassed toward the center of the macula.

Thinking through this basic anatomy, you can deduce certain techniques to improve your night-vision effectiveness. For example, the Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge recommends off-center viewing at night. This uses rods, which are 10,000 times more sensitive to light than cones. But, doing so also reduces “resolution” because the lens is designed to focus light on the fovea.

It takes 20-30 minutes for rods to fully adapt to low light. They literally need to re-charge. (A similar process also applies to cones.) Rods maintain a positive charge that dissipates when activated by light. Avoiding light allows rods to rebuild that charge.

The anatomy of the eye addresses sight, but sight and vision are not the same. Sight refers to the function of the organ. Eye sight is specifically concerned with acuity—how accurately can eyes see an image? Vision, on the other hand, is the brain’s processing of sight into understandable concepts. For example, sight accurately transmits an image of an orange ball to the brain, and vision recognizes it as a basketball. Some seeing problems are sight based, like empty field myopia, while others are vision based, such as false horizon. I think of it as eye games versus mind games. Age effects both sight and vision.

The Aging Eye

An old English maxim declares that time and tide wait for no man. As we age, our sight—and the accuracy of our vision—changes. Some changes, such as loss of near vision, need for more light, problems with glare, changes in color perception and drier eyes are a normal part of aging. Other changes signal serious problems.

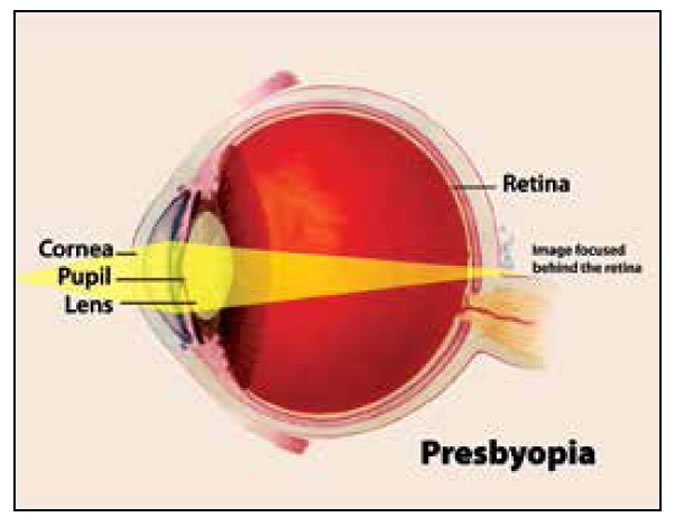

Around 40-years old, the lens becomes less flexible, making it difficult to focus on objects up close. This is presbyopia, and we need reading glasses. Also around 40, the muscles in the iris weaken. This contracts the pupil, requiring more light to see. Additionally, the pupil responds more slowly to changes in light, making those of us over 40 more sensitive to glare and rapid changes in light.

Aging brings risk for some serious eye conditions. The Mayo Clinic determined that half of 65-year olds have some cataract formation (a clouding of the lens). Fortunately, today’s medicine can correct the effects of cataracts. Risk of glaucoma—damage to the optic nerve due to eye pressure—also increases with age. Glaucoma starts with loss of peripheral vision, and leads to blindness if not treated. The leading cause of blindness among seniors, though, is age-related macular degeneration, which causes central vision to appear blurry, distorted, or dark.

Standards for a medical require “No acute or chronic pathological condition of either eye or adnexa that interferes with the proper function of an eye, that may reasonably be expected to progress to that degree, or that may reasonably be expected to be aggravated by flying.” (67.303) A serious eye condition could sideline a pilot. Otherwise, proper corrective lenses should keep you within the standards of 20/40 corrected vision.

Peeka-Vision

The baby game of peek-a-boo provides an understanding on how vision works. An interesting phenomenon occurs when playing with the baby; when your face is covered, the baby believes you have actually disappeared, thus the surprise when you re-emerge. The baby hasn’t learned that things can have other things behind them. As adults we take this for granted.

When we “see,” we draw on a colossal database of experience to turn sight into vision. This is how a two-dimensional painting can convey three dimensions. Changes in shading indicate depth and known objects, such as a tree, set scale. Our brain uses the same tricks when flying. These perception pathways create common visual tricks: runway width, runway slope, atmospheric and ground lighting illusions, for example.

Around 20-years old, a person reaches a sweet spot between organ ability, neuroplasticity and experience where vision is at a peak. As the years pass, we rely increasingly on experience to provide clues to the surrounding environment, increasing our susceptibility to illusions.

What We Can Do

The FAA provides some useful advice for night flying. View objects off center by 5-10 degrees to expose more rods to the image (better low-light sensitivity). Avoid bright lights for half an hour before flight. Keep cockpit and interior lights as dim as possible to maintain light sensitivity.

But what can a pilot do to mitigate or delay the normal effects of aging on sight? Maintaining overall health keeps the eye properly nourished and powered with oxygen and sugars. A regular eye exam can catch changes early, or at least make sure the cheaters (reading glasses) are up to snuff. Ultimately, we must recognize the change in acuity that comes with age and take steps to mitigate that risk.

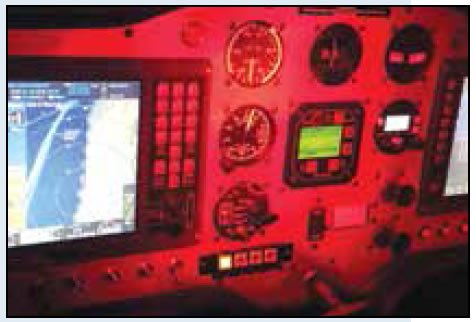

An instrument rating is a good start. Flying on instruments and following an instrument procedure to a runway will keep one from flying into dimly lit terra firma. Also, investments improving instrumentation and upgrading technology pay dividends. Change out the old small gauges for bigger ones, or a PFD. (It’s like getting the big print book at the library.) Adding an MFD or tablet with weather and terrain is also a good idea because it reduces the leading causes of night and IMC accidents.

Tales of Trouble

At night, with low visibility, the margin for error is miniscule. Conditions are perfect for disorientation and a single bad decision can easily go uncaught. IFR troubles at night frequently involve unseen weather or illusions during the visual segment of an approach.

Searching NTSB files for night and IMC, uncovered accidents caused by pilots entering convective activity and icing conditions. In one report, a pilot of a Seneca lost control while being vectored for an approach at night, over water, in heavy rain with thunderstorms in the area. He was a newly minted multi-engine pilot to boot and his instructor had prophetically admonished him not to fly “heavy IFR” until he gained more experience.

A 50-year old Mooney pilot augured in short of Burlington, Vermont under similar conditions. Forecasts called for thunderstorms and the airport was reporting two-miles visibility with precipitation and lightning in the area. The three horsemen of windshear, visual illusions, and spatial disorientation conspired on that dark and stormy night.

ASRS reports capture the effects of vision illusions. A Learjet crew mistakenly took the lights of a nearby driving range for the approach lighting system. The pilot reported, “Of course, my initial reaction to looking for a nice straight row of lights in front of me when I’m looking for a runway, is to line up with those lights.” Fortunately, the pilots were familiar with the airport and recognized the error.

Bright lights can quickly ruin night vision, leading to disorientation and botched landings. One pilot recounts being so blinded by the approach lights that he could barely find the runway. Bright approach lights—a common setting during low-visibility conditions—create the illusion of being closer to the runway. The result is flaring high and getting that sinking, stall-horn-blaring, bottom-clenching feeling while dropping towards the runway.

A Final Vision

Vision is a pilot’s most important sense. Humans rely heavily on it and instrument training re-enforces its preeminence over other inputs.

As we age, our eyes change. The lens becomes less supple, resulting in near-vision problems requiring reading glasses. Additionally, the muscles of the iris weaken, narrowing the pupil, which requires a brighter environment and slows the pupil’s response to changes in light.

While some changes in vision are inevitable, getting regular eye exams can diagnose serious problems and ensure a proper prescription. Recognizing the changes to sight and using appropriate safeguards will ensure night instrument flying can be safety accomplished. Most night IFR problems involve weather or visual illusions on approach. Mitigate these risks through currency, personal minimums, technology, or, better yet, all three. With age comes wisdom, and wisdom is the best antidote for tricks of the eye and mind.

Jordan Miller’s been a CFII for over 12 years and has been blaming poor landings on visual illusions for even longer.

Red Light district

Although the FAA is shying away from its use, red lighting used to be a night-flying essential. So, what’s the deal with red light? And why isn’t it that big of deal anymore?

Use of red lights may have originated in photography darkrooms, where the materials weren’t as sensitive to red. Interestingly, the translation to red light for night use makes sense for two reasons. First, rods are not as sensitive to red lights as other colors. Secondly, the fovea is packed with a majority of red-sensitive cones. The theory is that red preserves the rods’ night vision while activating cones in the fovea to see detail.

The best way to maintain night vision is using the lowest intensity light possible. Unfortunately, rods are much more sensitive to light—even red light—than cones. Therefore, using a red light to activate cones washes out night vision. A better solution for maintaining night vision is to use blue-green light, which the rods are more sensitive to than red light. This allows use of the lowest-intensity light possible.

A properly dimmed white light is better than a higher intensity red light. Red lights skew colors making chart reading difficult. What really matters for night vision is keeping the lights as dim as possible. If detailed vision is required, which it often is when flying, night acuity will be compromised in brighter light. —JM