Call me an optimist, but I like to think pilots and air traffic controllers get along pretty well. If both parties communicate and respect each other’s needs, planes flow smoothly through the national airspace system.

Of course, there isn’t always sunshine in paradise. Those are humans on either side of the radios. We hairless apes tend to be rather imperfect.

I hadn’t been working air traffic long before I already started noticing trends in the issues my coworkers and I were having with certain pilots. Call them recurring frustrations or pet peeves if you will. These little problems throw wrenches in our traffic flow and distract us from providing services to other aircraft.

Developing your skills as an instrument rated pilot naturally involves heavy interaction with ATC. Clearly expressing your intentions allows us to safely fit you in with the flow of other aircraft. Yours is just one of many flights we controllers are watching, so we need to communicate accurately and quickly.

Let’s cover some tips that can help us provide you with the service you desire.

Don’t Keep Secrets

Surprises are fun on birthdays. In the air or on an airport movement area—not so much. In fact, they’re about as pleasant as a surprise tax audit.

Imagine driving behind another car in the left of two lanes. Approaching an intersection, the other driver slows, kicks on their right turn signal, and changes to the right lane. You start accelerating since there’s now nothing but road ahead. Suddenly, the other guy hooks back into your lane and takes the left turn. You swerve to avoid smacking him.

Not a great feeling, right? That’s how it feels when a pilot hides his true intentions from us. Planning is a huge part of a controller’s job description. To plan, one needs information. Section 3-1-1 of FAA Order 7110.65—the ATC rule book—states, “Provide airport traffic control service based only upon observed or known traffic and airport conditions.” We make a plan on what we know. If the conditions change, we make a new plan.

In the driving scenario above, the driver’s turn signal and change to the right lane were “observed” traffic actions. Now, if you were talking to him on a cell phone and he told you, “I’m actually going to turn left,” then you would have “known” to adjust your actions accordingly.

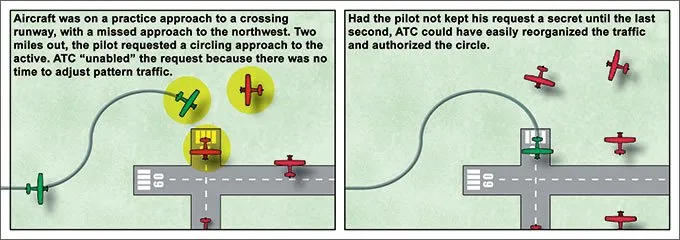

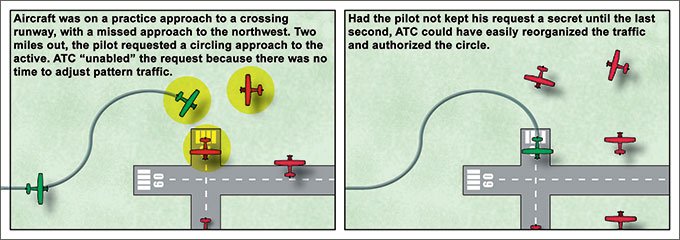

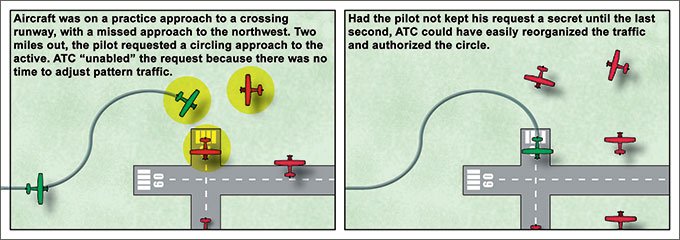

I recently had a Skyhawk leave a practice hold, eight miles west on a VOR approach to our east/west runway. Approach had assigned him a missed to the northwest for another approach. My north/south runway was full of pattern traffic, so I shifted them to left traffic on the east, away from the Skyhawk. I told the Skyhawk to execute his missed prior to the airport, preventing him from mixing it up with my pattern guys.

Two miles out, the Skyhawk asked for a circle to the active. “Unable,” I said. There were no gaps in the aircraft to my active runway. He begged on frequency that he needed a circle for his instrument check ride. “Unable circle,” I repeated. “Execute your northwest climb out.”

I’m a pilot too, but I had no pity for him. He had eight flying miles after his check-in, plus the twenty minutes he spent holding at the VOR before commencing the approach. He could have spoken up then and I would have made a gap. On his next pass, I did give him his circle, since by then I had time to arrange my pattern around him.

Don’t Go Rogue

As we’ve covered, last second requests aren’t fun. What about actually taking action without advising ATC? At a minimum it creates a serious distraction, and at the worst becomes life-threatening.

I’ve seen pilots do weird things. Last week, a Cherokee was taxiing to our active runway. Following him, I had a 737 whose IFR release window was in ten minutes, which—according to my experience—would give the Cherokee more than enough time to do a runup and depart. The Cherokee suddenly pulled a one-eighty towards a crossing taxiway and wound up beak-to-beak with the big guy. The Boeing visibly shuddered as its crew slammed on the brakes.

My first instinct was something was wrong. “Do you need assistance?” I asked the Cherokee. “No,” he replied, sounding a bit sheepish. “I was just trying to let the big guy pass and go first.” While his heart was in the right place, I wished he’d considered asking before giving a hundred passengers whiplash. I got him turned around and everyone continued as originally planned.

Taxiway incidents tend to be minor. On the runways and airways is where things get interesting. There was that one Cessna Caravan who was cruising in a cloud deck and climbed without my permission… right into a 50-passenger regional jet leveling off above him. Then there’s the Beech 1900 who stopped his assigned climb to 17,000 at 5000 to overfly its young copilot’s house so his proud family could take pictures. Nice gesture, but that put him in the face of crossing traffic, also at 5000.

I had to act quickly to correct these two distracting, dangerous situations. Both were completely avoidable had the pilots just asked first. The Cessna Caravan? “Expect a climb in five miles. Traffic overtaking you.” The Beech 1900? “Amend altitude. Maintain six thousand. Advise when ready to continue climb.” Make a reasonable request and ATC should hopefully grant it in accordance with airspace and traffic restrictions.

In emergency situations, it’s your right—indeed responsibility—as pilot in command to do whatever you deem necessary to preserve your safety. Outside of a crisis, taking unauthorized action on an IFR flight plan may win you anything from an on-frequency butt chewing to a shiny new pilot deviation, depending on the severity of the situation.

Don’t Be a Jerk

In the previous situations, the pilots just goofed and didn’t think through the full consequences of their actions. There didn’t appear to be any ill intent.

Occasionally, though, one has to share the frequency with a bona fide jackass. Pilots and controllers lean towards take-charge, type-A personalities, but there are some special individuals whose outright belligerence makes life miserable for everyone.

A week ago, one of my colleagues had a busy pattern filled with Skyhawks, a Seminole, an L-39 Albatross jet, and a couple fast military Texan trainers. Then came the proverbial back-breaking straw: a little, yellow Piper Super Cub sauntering in for some touch and goes. The six other pilots in the mix were professional, responsive, and courteous. The Cub driver? Apparently he’d taken out a lease on the sky and thought he’d kick out the interlopers.

Mr. Cub followed other planes so closely he appeared to be mating with them. Three times in a row, my friend had to send him around. “Aw man… c’mon!” he’d wail on the frequency. On the go-arounds, he’d hook crosswind as soon as possible, right into her downwind traffic. She’d try to stop him by extending his upwind, but he’d only reply to every third transmission, sprinkling those replies with snide commentary. His hearing was clearly selective.

My friend’s orderly pattern descended into chaos as she turned, spun, and extended airplanes to keep them out of this fool’s way. Who knows how much gas money other pilots burned just because this one guy didn’t know how to play nice with others? Finally, my friend had enough. “Either you full stop or you depart my airspace,” she told the Cub. He got the message and departed. He’s come back a few times since, and he’s been a lot more considerate.

ATC is in the customer service business. We try to accommodate pilots—even difficult ones—to a point, but like airlines and restaurants, if someone starts disrupting our other customers, we can curtail or deny services to them.

The ATC system and its users and managers aren’t perfect. However, clear communication and respect for the others sharing the sky can go a long way to making it better. I’m sincerely grateful the vast majority of pilots and controllers do know their stuff and make life easier for me, my coworkers and fellow aviators.

Tarrance Kramer handles secrets, surprises, and surly pilots while working traffic somewhere in the southern U.S.

I may spend some of my work day in a tall glass house, but I’m not afraid to throw stones. Any controller who says he never makes mistakes is full of it. A measure of a good controller is how rapidly he recognizes and corrects his own mistakes. Just like a good pilot, eh?

Unfortunately, some controller mistakes go unaddressed. Major events—such as any safety event involving an airliner—usually make the headlines, but small incidents or bad service occasionally slip through the cracks. No matter the type of incident, each shares two things: a chain of events leading to it, and an organization that oversees how that chain is investigated.

Here’s an example of the screwy things that can happen: I was working in that tall glass office when a voice came out of the blue. “Tower, Columbia Two Papa Echo inbound, ten north. We haven’t been able to reach anybody for sixty miles.”

Sixty miles? Yep, there was an unidentified radar target to the north. Tower airspace only goes out a few miles, so he was in our approach controller’s jurisdiction. I gave him the frequency. “Alrighty,” he said. “We’ll try your guys. Apparently the last guys didn’t want to talk to us. See ya in a bit.”

Unfortunately, those last ten miles weren’t easy. Our radar guys issued him a squawk. While waiting for Approach to say “radar contact,” the Columbia nearly collided with a Cessna in the practice area. A few minutes later, when he reached a five mile final, Approach brought in an airliner to our crossing runway. Approach gave the Columbia panic vectors to avoid a fabled “dead-ass tie” scenario.

Not to anyone’s surprise, our tower phone rang shortly after the Columbia landed. It goes without saying that he was ticked with the ATC service he’d received. As he spoke, however, it became clear the true magnitude of his situation was far worse than what we had perceived.

Apparently, he’d been on a three hundred mile IFR flight plan. That’s right. I-Freaking-R. Somehow, over the final sixty miles, he’d lost contact with the previous approach control facility and wound up in ours as an unidentified target ten miles from our airport.

IFR aircraft go “NORDO” (no radio contact) fairly often. Usually someone—ATC or pilot—botches a digit and poof, the plane’s lost in Frequency Land. ATC procedure in those cases is to call the next controller and advise them, “Hey, so-and-so’s NORDO.”

Talkie or no talkie, we still keep other traffic away from the IFR plane’s target. We can’t just terminate radar services in the blind like we can for VFR flight following planes. An IFR pilot needs to specifically cancel his IFR clearance. Since he was always IFR, any time he flew within 3 horizontal miles or 1000 vertical feet of another IFR airplane, that was potentially an ATC operational error. Not good!

How did this guy’s target get dropped off the radar? That’s the question. We controllers aren’t involved in the investigative process ourselves; I passed the Columbia pilot onto our supervisor. Management pulls the radar, audio data, and personnel statements. Once the facts are in place, they thoroughly assess the situation. If the cause was human error, the personnel involved will receive anything from additional training to a full reprimand.

ATC provides a service. If you really have a bad experience, let us know. FBO’s usually have the numbers to their local ATC facility handy. The staff will put the situation under the microscope and hopefully fix it. —TK