The word “Model” is in the title because it articulates ways to achieve flying excellence without a canned set of rules. Tailor the code to help you become the best, safest aviator possible.

Prerequisites

The first prerequisite is a clear understanding of the fundamentals of flight. The code is not specific, but those four fundamentals from your early flying days come to mind.

The code works only if an aviator wants to be the best possible. One aircraft owner told me, “I’m not a very good pilot,” as if to say, “I don’t care,” gauging his minimal adequacy as incapable of improvement. A better view: “I love flying because I can be as good as I want.”

We survey all seven code sections: General Responsibilities of Aviators; Passengers and People on the Surface; Training and Proficiency; Security; Environmental Issues; Use of Technology; and, last, Advancement and Promotion of Aviation. You can read the full document at sercureav.com

Aviators’ Responsibilities

Safety First Flying is serious stuff. Airplanes fly by virtue of delicate laws of physics. If you bend some lift vanishes, and it’s a bad day. Respect the medium.

Excellence in Airmanship The word “Airmanship” may seem oldfashioned, even misogynistic. Broadly, it encompasses the entire pilot skillset: stick-and-rudder skills, leadership responsibility that comes with authority to be PIC, applying what you know, and self-discipline.

You have self-discipline if you do the right thing, whether or not anyone is looking. The “How will it look on the FAA accident report?” attitude looks silly to a disciplined pilot. If you fly as you trained on your flight test, what difference does it make even if the FAA Administrator is riding shotgun?

Sound Judgment and ADM A sage airline pilot once advised me, “When in doubt, do the right thing.” I sighed in frustration, expecting more. In retrospect, I think he was saying, “Deep down, you know the right thing to do, so do it.”

We approach aviation with basic common sense. Add the vertical dimension to a shot of aeronautical decision- making, and stir. In the words of astronaut Frank Borman, “A superior pilot uses his superior judgment to avoid situations which require the use of his superior skill.”

Manage Risk As a pilot taxied, an adjacent helicopter lifted off and started to pass over her aircraft. She hit the brakes so the helo would cross ahead. That’s risk management in action.

The FAA says, “A key element of risk decision-making is determining if the risk is justified.” Never let anyone run your airplane. Gen. Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in 1947 and passed away recently at 97 after a career full of risks. He was reputed to “never let someone else get in his head.” It worked for him, and it can work for us.

Situational Awareness Good SA means we know what’s going on around us. Build an egg timer in your brain: avoid looking down in VMC for more than a few seconds. Traffic can appear in a heartbeat.

Aspire to Professionalism Evaluate your performance after every flight. What did you do well; what poorly? Don’t beat yourself up; just aim to do better next time. Professionalism will come by itself.

Be Responsible and Courteous Working with ATC and cooperating with other pilots is one of the joys of aviation. In flying, courtesy remains the order of the day. As a community, we are safest when we look out for each other.

Obey Laws and Regulations A bigshot pilot told me that regulations were just guidelines. He had always regarded the law that way, and it had always worked for him. Not so for the FAA. If they zero in on you, you’ll have to explain— and it had better be good.

Passengers and People

Passenger Safety Comes Before Comfort The passenger was airsick in bumpy, convective weather. The pilot gave him a plastic bag but concentrated on flying the airplane, even as the passenger tried to feed him homemade cookies. Safety first, comfort second.

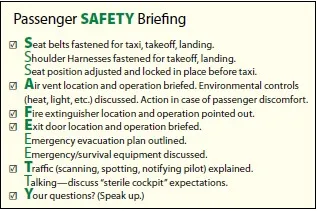

Brief Passengers Conduct a thorough safety briefing. Inform your guests about the planned flight and possible risks like turbulence. Take pressure off yourself by setting expectations, such as reasons to return or land short of the destination. Advise there will be no aerobatics or unusual maneuvers.

Prevent Unsafe Conduct Escort passengers to and from the airplane, warn them to leave the controls alone, keep their seatbelts on, and how to operate the door. Headsets are a great idea. Avoid fueling with passengers aboard.

Don’t Scare Them Fly as smoothly as you can. Address passengers’ concerns and anxieties. Inform them that they needn’t fly if they don’t want to. Could they present a safety or security issue, perhaps transporting illegal substances, HAZMAT, or weapons? Ask if they have flown in small aircraft. Willing passengers can hold maps, spot aircraft, and the like. You’re responsible for the safety of people on the ground, too.

Training and Proficiency

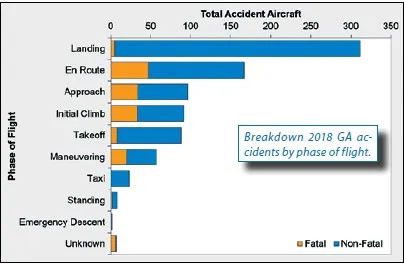

Get Recurrent Training The code says, “Recognize, accept, and plan for the costs of implementing proper safety practices,” of which recurrent training is a part. Recurrent air and ground training maintains proficiency. Since legal is not necessarily proficient, set your sights on being the best you can be.

Participate in Flight Safety Programs For now, this means web seminars as from AOPA or WINGS, or even watching training videos on YouTube. In-person safety meetings will return.

Remain Vigilant and Avoid Complacency Jerome Lederer, famously dubbed “Mr. Aviation Safety,” said in 1967 that “you always have to fight complacency—you need formal programs to ensure that safety is always kept in mind.” The code recommends a meticulous Safety Management System as outlined in our January 2021 article, “Safety Management.” The code recommends practicing partial panel at least every three months, an IPC every six months, and an annual Flight Review.

Cope Effectively With Emergencies We fly the way we train. In a memorable emergency, the Crew Alert System started screaming engine troubles with bells, aural warnings, and visual alarms. The engine coughed, sputtered, and died. My emergency ABC training kicked in: airspeed, best place to land, checklist if able. I yelled at the student, “Did you do anything?” He reached over, and (un) did something. The engine started; the alarms cleared. He had moved the fuel selector past the detent and shut off the fuel. The training had prepared us for the worst, but not for self-inflicted emergencies: What did you do last?

Security

Security of People and Property An individual entered our flight school, asking odd, disjointed questions about learning to fly. We couldn’t know he was scouting for loose airplane keys.

That night, he entered the airport by an unsecured route. Hotwiring one of the Skyhawks, he learned that taxiing with the wheel doesn’t work. He crashed and ran away.

The offender proved to be an auto thief out on bail, apparently looking to broaden his horizons. Our security processes forced him to find another way. Persistence pays, even for crooks.

Vigilance Active CFIs get initial and recurrent security training. TSA recommends pilots query anyone who seems out of place on the airport. We must not interfere but advise our management or call the police. Free online TSA training is available from Gleim, King Schools, and others. CFI ticket not required.

Reckless behavior invites an informal word before calling the FAA. If illegal, it’s a matter for the FAA or the cops. As always, “If you see something, say something.”

Security Regulations Check NOTAMs and TFRs before flight. Review intercept procedures in AIM 5−6−13 periodically as part of your SMS package and monitor 121.5 when able. Add the General Aviation Secure Hotline (866-427-3287) to the contact list on your mobile telephone.

Avoid SUA Only ATC knows for sure (well, mostly) which airspace is hot. Your IFR clearance can incorrectly route you through SUA, so check it first on a map. Before you deviate from an active flight plan, inform ATC.

Preserve the Environment

Mitigate Avgas is a significant contributor to lead emissions in the U.S. To minimize your aircraft’s environmental impact, use the most favorable altitudes and shortest routes.

Minimize Chemical Discharge Today we pour avgas back into the tank through a fuel strainer. Look around for red cans to deposit tested fuel. Other chemicals include oil spillage, degreasing reagents, and de-icing fluids.

Environmentally Sensitive Areas Aircraft are requested to maintain a minimum altitude of 2000 feet above the land’s surface and waters administered by the National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Forest Service. Note that this is not a regulation. See AIM 7-5-6 for details.

Noise Abatement Many airports have preferred runways that route departures around congested areas. DPs account for noise abatement. Given a heading to fly after departure, it could be a noise abatement turn. Plan during preflight to fly above or avoid noisesensitive areas. Follow noise abatement procedures, which might include reducing power and RPM as soon as possible after takeoff.

HAZMAT A hazardous material is any substance or material capable of posing an unreasonable risk to health, safety, and property when transported in commerce. HAZMAT can be toxic, poisonous, flammable, explosive, irritating, or radioactive. Lithium batteries, dry ice, even aerosol whipped cream can be dangerous. See faa.gov/hazmat

Technology

Get Familiar There are three categories of avionics: Communications, Navigation, and Surveillance (transponders, radar or ADS-B-Out.) Today’s avionics are feature-rich, but you need only know the essentials to get along. If you can get what you need when you need it without fumbling or guessing, you’re good to go.

Use the Radio Obtain the AWOS/ ASOS/ATIS to find out what to expect in the terminal area. Routine ATIS updates occur 50 minutes after the hour— be sure you have the current one. Make accurate position reports approaching nontower airports and other high-risk areas.

Turn on Surveillance Activate your transponder after engine start. ADS-B Out activates automatically. A common ADS-B operational error is when the flight ID transmitted by ADS-B Out does not match the call sign specified in an IFR flight plan.

Double Up An IFR Bonanza pilot in central Florida’s dark territory lost his electrical system. He saved his life because he had his handheld charged, ready, and cabled to its own antenna.

Log Sim Time You can do so much in an FTD, BATD, or AATD, like partial panel and multiple failures, inexpensively, making lots of practice economical.

Advance and Promote Aviation

Keep the Code The Code of Conduct guide is a multifaceted guide to help us be the best pilots and aviation citizens we can be. It’s an attitude, a process that we can work on every day whether we fly or not.

Volunteer As with joining AOPA, NAFI, SAFE, or serving as an FAA FAASTeam member, to support aviation. Become a volunteer pilot with Angel Flight or a similar organization. Consider joining the Civil Air Patrol, the Coast Guard Auxiliary, or Explorer Scouts.

Appreciate We can’t thank controllers and service personnel like AMTs often enough for the phenomenal job they do.

Advance Aviation Culture Be an aviation ambassador to the public. Refute misinformation and encourage potential student pilots. Remember that your actions reflect on the entire aviation community.

Promote Ethical Behavior Promote safety among other pilots. In all your aviation dealings, apply the highest ethical principles. Try to resolve disputes quickly and informally.

Mentor Let’s make joining aviation easier through Discovery flights and AOPA’s You Can Fly program. Young people will propel aviation into the new world of NEXTGEN and beyond. An earlier generation left us an incredible legacy. Now we must pass it on.