Now that many of us have already met the U.S. January 1, 2020 deadline for ADS-B equipage, and most of the procrastinators are at least making plans, along comes a general awareness that what we do in the U.S. is unlikely to permit us to fly into Canada after their equipage deadline. Uh, now what?

Quick Review

Just to make sure you understand what’s up, let’s review. In the U.S., we’ve got excellent radar coverage, so all those radar sites have been modified to understand your aircraft’s ADS-B out transmissions. In those areas where radar sites don’t quite have adequate coverage, the FAA has added ground stations specifically to receive your ADS-B Out. The bottom line is that the FAA has sufficient ground-based coverage to know where you are almost all the time, using your ADS-B Out.

Meeting the U.S. ADS-B Out mandate can be done in one of two ways. First, you can install a Universal Access Transceiver, UAT, which operates on 978 MHz. Often, a UAT will also give you the ADS-B In benefits, but the popular inexpensive products are ADS-B Out only UATs.

UATs meet U.S. requirements in all required airspace except Class A. There, you need a 1090 MHz solution, essentially a transponder that adds ADS-B Out data to its transmission. A 1090 solution meets the U.S. requirement in all airspace.

Interrogate or Not

Our now-legacy Mode C transponders, like that mythical obedient child, only speak when spoken to. In other words, they’re silent unless interrogated. Interrogation comes primarily from those ground-based radar systems, but also from active traffic systems (TCAS) on larger aircraft.

With ADS-B, that same interrogation still produces the same response, but that response is now expanded in an ADS-B Out transponder to add the ADS-B Out data. But in addition to responding to an interrogation, an ADS-B Out transponder must broadcast its ADS-B Out data in the blind once a second (in two bursts, a half-second apart). The reason is to allow that aircraft to be seen by others (and ATC stations) in areas where there is no active interrogation.

Canada is Different

Canada has far more remote, even inaccessible, areas than the U.S. and still has large areas where there is at best limited radar coverage. Thus, in Canada, a ground-based ADS-B solution for ATC similar to that in the U.S. is impractical. Nav Canada recognized this early on and invested heavily in the satellite-based ADS-B systems provided by Aireon.

The first big difference between the ADS-B systems in Canada and in the U.S. is that 978 MHz UAT ADS-B systems are useless in Canada. In fact, they’re essentially useless outside the U.S. So, that new UAT-based system you installed to meet the U.S. mandate is only good in the U.S. ADS-B Out in Canada (and, indeed, anywhere it is mandated in the rest of the world) requires a 1090 MHz signal—an ADS-B Out transponder. Now we tell you…

The next big difference is since Nav Canada has insufficient ground-based resources to provide coverage in remote areas, their selection of satellite-based ADS-B monitoring means you’ve got to have an ADS-B Out transponder antenna on the top of your aircraft. But wait; there’s more. Since they do have some ground-based interrogations, you also still need an ADS-B Out transponder antenna on the bottom of the aircraft, just as you’ve had for years with your Mode C transponder.

Here’s where it gets interesting. These antennas must be on the same system. You can’t continue to use your single-antenna system on the bottom and add another single-antenna system on top, because of the strict timing requirements of the secondary surveillance radar (SSR) that’s at the heart of the 1090 signal. That also means that you can’t just add a splitter and a second antenna to a single-antenna ADS-B Out transponder.

Diversity

The way you can use a single transponder system connected to two antennas is through a technique called Diversity. Garmin has quietly been offering a Diversity option in its transponders for years. The way they do it is that each of the two antennas is tied to a dedicated receiver. When an interrogation is received, the two receivers vote to see who got the strongest signal. In some cases, it’ll be close; in other cases one antenna might only get an extremely weak interrogation signal while the other gets a clear, strong signal.

The receiver with the strongest received interrogation signal then tells the lone transmitter in the transponder to reply through that receiver’s antenna. In this way, the reply is sent out the antenna that received the strongest interrogation.

But, recall that with ADS-B Out, the transponder is also required to broadcast it’s ADS-B data once a second, whether it’s interrogated or not. With Diversity, the transponder still does exactly that, but alternates between the top and bottom antennas—out the bottom antenna, then a second later out the top, then another second later, out the bottom, and so on. Note that the Aireon satellite system doesn’t interrogate; it relies on this unsolicited ADS-B Out broadcast.

The base price of Garmin’s popular GTX 345 ADS-B In and Out transponder is $4995. Adding the Diversity option takes it to $7995 plus the cost of installing a second antenna, which often isn’t trivial because of the labor to access the cabin roof, and can reach as much as another couple thousand dollars in a pressurized aircraft. Note that at this time, the choice of Diversity from Garmin must be made at purchase; there currently is no upgrade path.

When?

Unlike the U.S. all-or-nothing ADS-B Out equipage deadline of January 1, 2020, Nav Canada has phased its implementation deadlines. If you fly in Canada in Class A airspace or in Class E above FL600, you must be equipped by February 25, 2021 (Phase 1). Phase 2 adds Class B airspace, which in Canada is essentially anything above 12,500 feet, with a deadline of January 27, 2022.

Plans for a Phase 3, likely to add nearly all controlled airspace, are still fluid, but the deadline will not be before January 1, 2023. Nav Canada has said that current ADS-B Out transponders with Diversity meet their Phase 1 and Phase 2 equipage requirements. Indeed, an ADS-B Out transponder with Diversity is currently the only way to meet the requirements in Canada.

Deciding Now?

Say you’re one of those U.S. aircraft owners who’s not yet added ADS-B. What should you do now? If you don’t plan to fly outside of the U.S., you can ignore this entire article and choose the option that otherwise suits you best. Note that when we say, “outside of the U.S.” it’s best to consider that to be the continental U.S.; the FAA is at least looking at Aireon satellite-based ADS-B reception in the Caribbean, but is a long way from a decision.

But, if there’s a likelihood that you’ll fly in Canada after 2021 (Phase 2 or Phase 3), or anywhere Diversity might be required, you should probably just bite the bullet now and install an ADS-B transponder with Diversity.

If you’re in that limbo where your flying is in the continental U.S. but you might someday go to Canada or even to another country using satellite ADS-B, you could skip the Diversity option now to save a few thousand dollars, and just equip as required when faced with the actual need, perhaps hoping that your current ADS-B transponder will by then be upgradable to Diversity or that there will be cheaper options. Next time the headliner is off though, consider running at least a cable, if not an antenna.

These are tough choices.

Antenna Primer

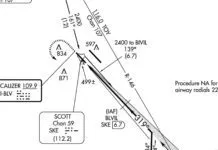

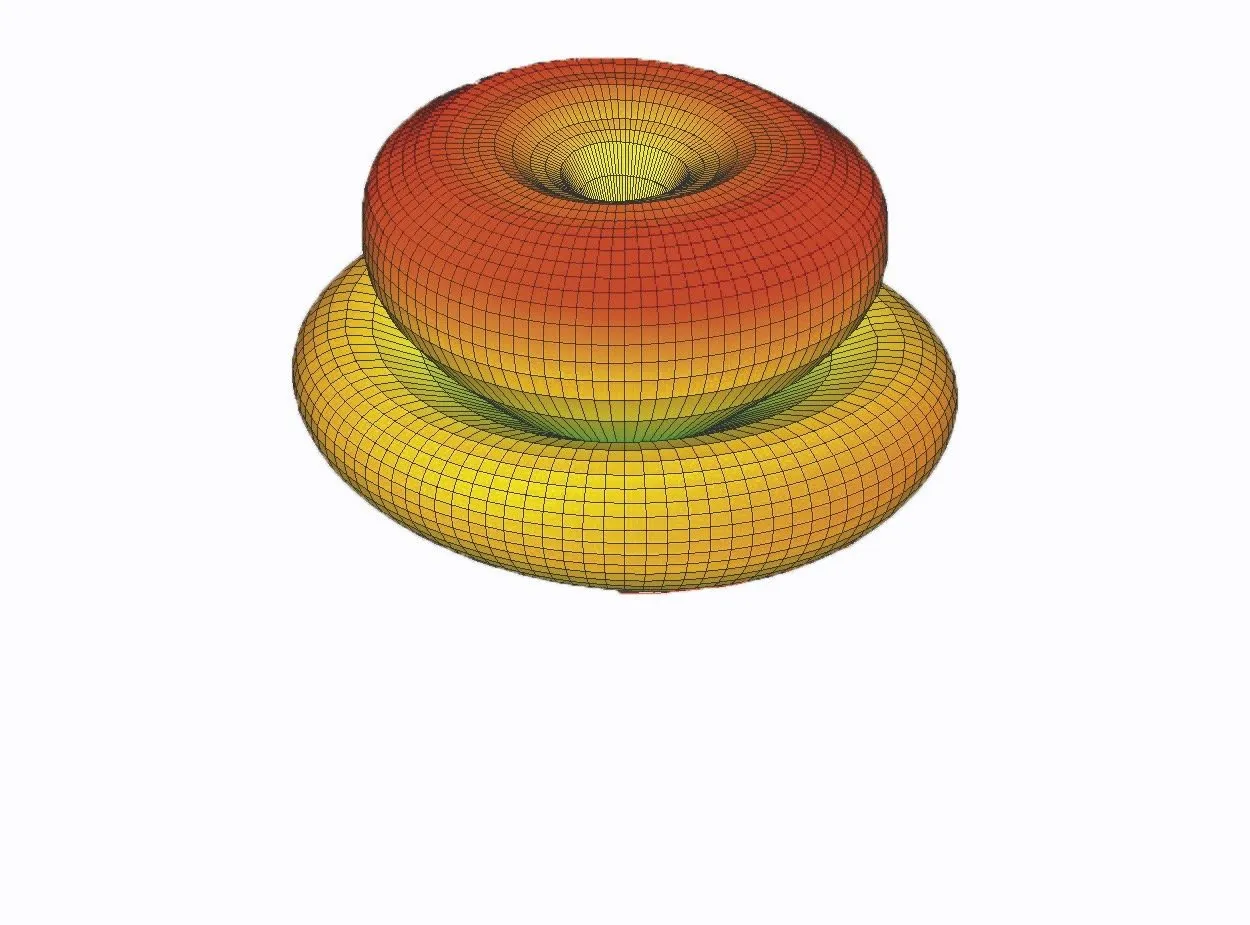

There are two common transponder antennas in use today: whip and blade. Although they’re physically different, they’re electrically about the same. They’re both -wave monopole antennas designed to be mounted on a ground plane (typically, the aircraft skin). Think of the blade as simply a whip encased in an aerodynamic shroud. When mounted on the top or bottom of our aircraft, they yield a radiation pattern with vertical polarization, shaped much like a donut radiating out horizontally from the sides of the whip antenna (with the whip in the middle of the donut hole). See the diagram at the bottom.

Note that the strongest radiation (the red) isn’t directly to the sides, parallel to the ground plane, but angled up and away from the ground plane. The size, shape, and curvature of the ground plane affect the angle of maximum radiation, but the drawing is a general guide for the radiation of our transponder antennas.

Note that there is almost no radiation directly off the end of the antenna. Thus, for best performance, the receiver must be a bit to the side of the aircraft, not directly overhead or below. With ground stations, the shorter distances quickly yield sufficient angular offset for good performance, but a satellite will effectively remain essentially overhead for a longer time.

Also note that the specs for our transponders require operation out to only 185 miles. The Aireon satellites orbit about 485 miles from the earth, so you’re already operating at excessive distances. Add the radiation pattern of our antennas, and you’d expect satellite reception to be severely disadvantaged.

Tests, though, have shown that the system works adequately. But one has to wonder that with increasing congestion how long that will last. If I had to guess, I might speculate that today’s ADS-B-by-satellite system won’t be the last word. For me, that means delaying my satellite-based solution purchase as long as possible. —Nirmala Ganapathy, PhD

Frank Bowlin, uncharacteristically ahead of the power curve, equipped years ago with an ADS-B Out transponder. He’s now considering whether to rip that out and replace it with an ADS-B Out transponder with Diversity to fly in Canada.