Recognizing where operations and procedures fail to provide adequate safety is the first step in making positive changes in the National Airspace System. Pilots and controllers stand on the front lines, so it’s up to us to be vigilant about safety lapses and take steps to improve our system.

Our Role in Change

Let’s look at a unique example from the past that aviation professionals identified. But before we get into the process of change, it’s important to consider our limitations—more specifically, the limitations of our knowledge. In the vast and complex world of aviation, pilots and air traffic controllers alike go through rigorous training to give us the knowledge and understanding needed to function safely within the system.

As aviation professionals, we have an impressive amount of regulatory and technical knowledge rattling around in our (big?) heads. Yet, despite the quality and scope of our training, we still find gaps in our knowledge and understanding. Most of us are well aware of this. But some may not have considered that while pilots and controllers go through different training processes, we still operate in the same aviation system.

We work together in a system designed to ensure the safety of flight over the United States. Yet, we have two different perspectives of the operations and procedures. Of course, there is overlap and congruency in our knowledge, and our training covers those things. But since we go through separate training programs it’s nearly a given that there will be gaps between our understanding of things. Despite that, we share the same goal and should do our best to address all issues that might prevent us from achieving it.

Like the age-old adage, pilots and controllers are two sides of the same coin. Safety is our unity and our shared purpose. So if we are two sides of the same coin, look at the gap in knowledge and understanding as the edge of that coin. Inconsistency exists in those edges, where our professions come together, and where one side or the other may not see a critical component of safety.

Because air traffic controllers don’t go through the same training as pilots, we don’t always have comprehensive knowledge on specific requirements and restrictions that pilots face. This can lead to miscommunication or misunderstandings during critical phases of flight. In this example, air traffic controllers were clearing aircraft to cross the IAP at or above an altitude that turned out to be unsafe for executing the procedure turn.

Remember that despite the scope and quality of training in the aviation world, we can always learn more. We should be lifelong learners and always seek to expand our knowledge. It is crucial to remember we aren’t perfect, and neither is the National Airspace System. There will always be threats to safety. Recognizing the significance of these issues becomes paramount in establishing communication and collaboration between pilots and air traffic controllers so we can work together to fix them. Improved awareness of these threats to safety can facilitate the development of training programs and procedures aimed to address and mitigate such issues. We should always keep our eyes open and examine the edge of that coin.

The Example

In late October of 2015 the National Business Aviation Association held meetings with the Aeronautical Charting Forum (now the Aeronautical Charting Meeting, ACM). The meetings discussed a recommendation to change the charting of approach procedures for HILPTs. HILPTs provide a course reversal to align with final. They also provide protected airspace for pilots to descend as needed to reach the FAF altitude. The U.S. Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS) criteria, which allow aircraft deceleration and configuration for the final approach, are designed to ensure separation from terrain and obstacles.

In late October of 2015 the National Business Aviation Association held meetings with the Aeronautical Charting Forum (now the Aeronautical Charting Meeting, ACM). The meetings discussed a recommendation to change the charting of approach procedures for HILPTs. HILPTs provide a course reversal to align with final. They also provide protected airspace for pilots to descend as needed to reach the FAF altitude. The U.S. Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS) criteria, which allow aircraft deceleration and configuration for the final approach, are designed to ensure separation from terrain and obstacles.

In cases like this example, terrain and obstacles require TERPS criteria to be more restrictive on the safe altitude for HILPT descents. These safe altitudes for holding in the published HILPTs are lower than the altitudes that were sometimes used in clearances for the approach. Because controllers, and many pilots, didn’t know about the safety gap between these clearances and the safe altitudes for the HILPT (according to the TERPS), there was a very real threat to safety.

The problem with the chart (at the time) was that the TERPS maximum safe holding altitude for these HILPTs was not published on the approach charts. It was a gap hiding on the edge of the coin, creating a big problem.

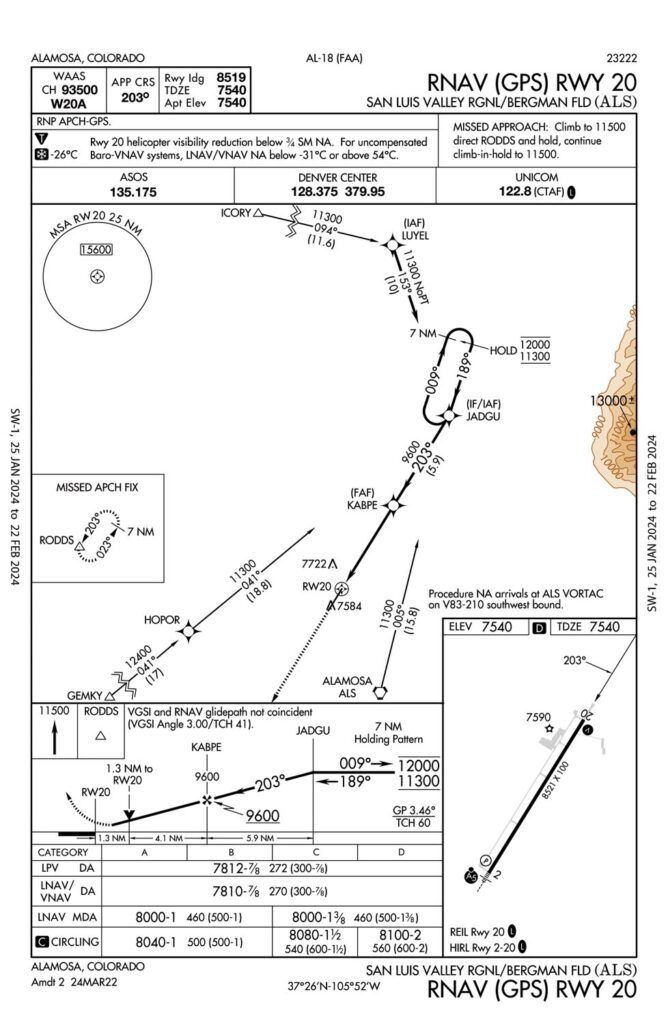

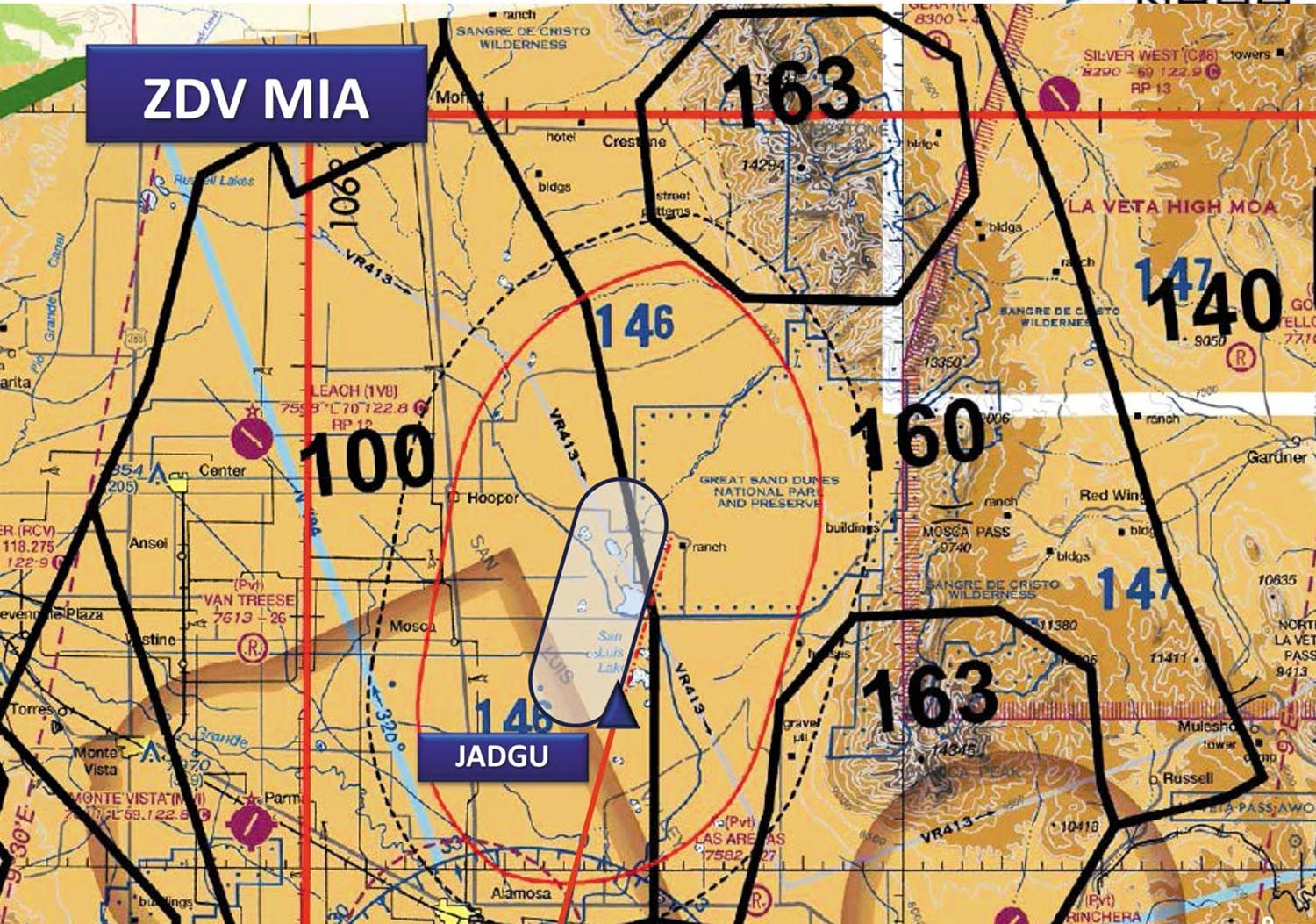

The RNAV (GPS) Rwy 20 approach at Alamosa, Colorado (KALS) had the HILPT altitude at JADGU at 10,800 feet MSL. However, the TERPS for the maximum holding altitude at JADGU was 12,000 feet. Since the approach chart didn’t show 12,000 feet as a maximum safe altitude for the HILPT, controllers would issue clearances “at or above” 10,800 feet or commonly 11,000. Thus, they didn’t assure safe separation in the HILPT. This is a big no-no for ATC. Our primary concern for IFR aircraft is ensured separation from other aircraft, obstacles, and terrain.

KALS sits in a valley to the west of the Sangre De Cristo mountain range. Minimum IFR Altitudes over those mountains is 16,000 as shown in the MIA chart, making approaches from the east even more difficult. JADGU is located so close to those MIAs of 16,000 that it is (even now) impossible for controllers to clear an aircraft direct to JADGU from the east for an approach. In order for those aircraft to cross JADGU at the maximum HILPT altitude of 12,000 feet, they would need to descend 4000 feet in a little over 2 miles.

At the time, controllers weren’t considering the TERPS information. It just wasn’t something we were trained on and it isn’t even readily available at our sectors. Because of this, clearances into KALS for an approach from the east would be “cross JADGU at or above 16,000…” This clearance was even more dangerous than a clearance “at or above 11,000” since the holding pattern is larger at the higher altitude, putting aircraft even closer to the terrain. There was no assurance of terrain separation.

I expect most controllers lost their minds when they learned this. Can you imagine learning that a clearance you regularly issued could have resulted in a collision with terrain? If something like that were to happen, there would absolutely be an investigation and you can bet your last tank of oxygen that the lawyers would be grilling the controller on why he didn’t know the clearance was unsafe. Let’s just say there was probably an adult beverage or two consumed when the controllers got home with that news weighing heavily on their minds.

As a result of this identified issue, the NBAA proposed that the same sort of charting requirements that are applicable to “at or above” restrictions at the IAF should be used to chart “at or below” restrictions when a maximum holding altitude is specified in the TERPS for the approach. This change would make it so air traffic controllers and pilots would be aware of the maximum holding altitude at HILPTs. The NBAA invited those attending the ACM to assist in determining the preferred method. After several meetings and some deliberation, the format and location of this information was determined and implemented. The maximum holding altitudes at HILPTs that you see today are a direct result of this process.

What You Can Do

At this point you might be thinking, “Okay Mac, that’s interesting and I appreciate the information…but how do I make this sort of change? What can I do?”

I’m glad you asked. There are two ways that you can take steps to make changes in the National Airspace System. If you want to make changes to policy, design, criteria, and charting of instrument flight procedures (IFP) relating to informational content and design of aeronautical charts and flight information products, all you need to do is take a short trip into Google-land and search for the Aeronautical Charting Meeting webpage. The ACM was created by the FAA to provide aviation professionals a platform to offer comments on these things. The objective of the ACM is to:

- Identify issues concerning safety and usefulness of aeronautical charts and flight information products/services.

- Discuss and evaluate proposals concerning aeronautical charts and flight information publications, digital aeronautical products, database coding, instrument flight procedures, and instrument flight procedure development, policy, and design.

- Provide an opportunity for government and interested participants to brief and/or discuss new navigation concepts, terminal instrument procedures (TERPS) policy/criteria changes, and charting specifications and methodologies.

Meetings are open to the public and a minimum of two joint meetings are held per year. Some specific group meetings may be called, but that is at the discretion of the individual group chair. I expect issues brought to his/her attention that require immediate attention—like the example above—will warrant an unscheduled meeting.

The second way you can make change in the NAS is by petitioning the FAA Administrator that the FAA adopt, amend, or repeal a regulation. I’ve never personally had any experience in a process like this, but it seems pretty straight forward … until you remember you’re dealing with the government. Take a look at this laundry list of requirements for making this sort of change according to (deep breath) Title 14, Ch. 1, Subchapter B, Part 11, Subpart A, §11.71.

You must include the following information in your petition:

- Your name and mailing address and, if you wish, other contact information such as a fax number, telephone number, or e-mail address.

- An explanation of your proposed action and its purpose.

- The language you propose for a new or amended rule, or the language you would remove from a current rule.

- An explanation of why your proposed action would be in the public interest.

- Information and arguments that support your proposed action, including relevant technical and scientific data available to you.

- Any specific facts or circumstances that support or demonstrate the need for the action you propose.

In the process of considering your petition, you might be asked to provide information or data available to you about the following:

- The costs and benefits of your proposed action to society in general, and identifiable groups within society in particular.

- The regulatory burden of your proposed action on small businesses, small organizations, small governmental jurisdictions, and Indian tribes.

- The recordkeeping and reporting burdens of your proposed action and whom the burdens would affect.

- The effect of your proposed action on the quality of the natural and social environments.

It does seem reasonable that you need to justify your proposal and provide good data to back it up. But that’s a process. However, if you have a worthy cause, nothing should stand in your way. Make every effort possible to change things for the better. As you saw in our example, the system isn’t perfect and we should take it upon ourselves to make it better.

Considering the future—the NAS is full of perplexing procedures and information, leaving us with more questions than answers. There will be times when you even understand the procedure, but still feel unsafe about the operation. Why not just write it up? Take that time to contribute to aviation and improve the NAS. In all likelihood, you’ll make the system safer for everyone and perhaps even save a life.

Mac Lawler has been an air traffic controller for almost 13 years. He contributes to training and simulation development for operational controllers. He also works part-time at ATC for Pilots, an online aviation school, developing eLearning modules to teach pilots how to work more effectively with ATC.