You’ve seen and almost certainly used a WSI Pilotbrief weather station in your travels. It’s almost a required ritual of flight: Stop by the screen and make a last check of the radar or TFRs while you finish your lukewarm coffee.

As a pilot, do you care who’s behind the weather information you see at the FBO or in the cockpit? The answer is largely, “No.” But there are some differences between what you get from a briefer, on the web or from the competing XM weather provided by Baron Services. What we found more interesting was what a weather service must do in collecting, distilling and delivering the weather in a format on which pilots can depend.

Who Is WSI?

The company has been around for over 30 years and does a lot more than aviation weather. They’re now a Weather Channel company, so they’re a source of weather data to a host of media outlets, as well as commodities traders and the energy sector.

That said, 40 percent of their business is aviation related. The FBO weather represents a piece of that. If you went behind the scenes at several major airlines, you’d find WSI weather there. WSI has an in-flight service similar to XM weather, but only available on certain installed systems. You won’t find any WSI weather for portables; XM owns that market. WSI did get the contract to provide weather for the ADS-B system, so if you become fully ADS-B compliant with the ability to receive datalink weather from ADS-B ground stations, that’ll be WSI weather.

The airline forecasting was an interesting insight for us. Remember that Part 121 and 135 operators can be restricted from flying a route or be forced to take fuel instead of paying cargo just due to a forecast. WSI is an approved weather service, which means the airline can choose to use a WSI forecast instead of a National Weather Service (NWS) forecast in the right situation. For example, the NWS TAF for an airport might be several hours old, yet one to replace it—and maybe solve the airline’s planning problem—won’t come until after the flight is due to depart. WSI can make a custom TAF with the latest data. It might not be any better, but if it is, that could save the airline real money.

WSI also offers versions of turbulence or icing forecasts with finer resolution than NWS sources. Don’t expect that in the FBO or GA cockpit, however. Those are premium services for premium-paying customers.

Top Products, Custom Tweaks

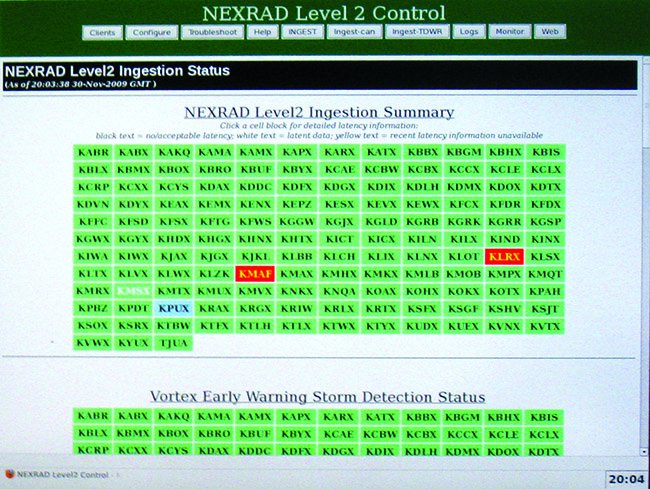

NEXRAD is what pilots want most from WSI Pilotbrief stations, with 46 percent of the page requests being some kind of radar. The next highest product request is textual weather, which clocks in at just 10 percent. NEXRAD from the TV or the web differs from what you see from WSI or XM weather (see sidebar). WSI and XM even handle NEXRAD differently, so it’s good to know what you’re seeing, or not seeing, with each.

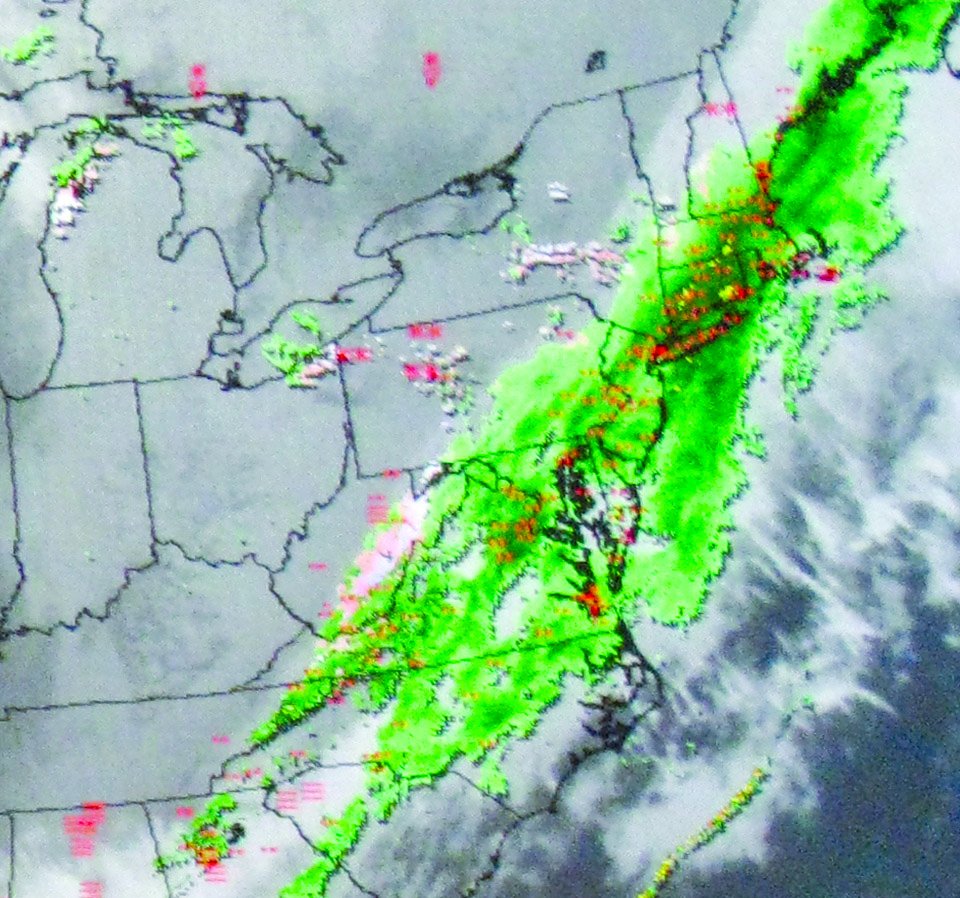

WSI NOWrad (their branded NEXRAD product) uses base reflectivity from the 0.5-degree tilt of the radar sites. This is the closest to the ground the radar looks. (Other scans are available all the way to looking straight up, which is used to gather data on wind velocities). How high the 0.5-degree scan works out to in feet AGL depends on how far away a given point is from the radar antenna. As a general rule, you should assume that NOWrad shows precipitation that’s in the sky at 10,000 feet and below.

This view of the precip has benefits and drawbacks. It might miss a rapidly-developing storm, where there just aren’t enough big droplets down low to show, even though there is stuff brewing in a column of air reaching into the flight levels. That’s why some lightning detection paired with NOWrad is a good idea.

On the plus side, using only the low-angle scan preserves much of the valuable gradient information. For example, if there is an anvil that’s overhanging in front of a developed storm, the NOWrad will show a clear area (under the anvil) with an area that rapidly moves from green to yellow to red right next to it. Tight color contours on NEXRAD of any kind are areas to avoid. If the data was composited with higher-elevation scans, the area under the anvil might be a uniform, unthreatening green due to water and ice in the overhanging cloud. A pilot thinking that looked like a good place to go could be in for a nasty, turbulent surprise.

Other key things to know about WSI products are that the winds and temps aloft are updated hourly, that their storm-center data is just the storm center from the NWS storm table (XM computes custom storm centers based on threat-detection), and their lightning detection includes cloud-to-cloud lightning (XM is cloud-to-ground only).

The Power of Detailed Data

The NWS Rapid Update Cycle weather model (RUC) is a key data source for the TAFs and Area Forecasts GA pilots see. WSI runs its own version of the RUC, which models the atmosphere in a 3D grid of points six km apart. Amazingly, it only takes 30 minutes to run a three-hour forecast RUC. WSI runs that RUC every hour and longer RUC every three hours to predict the next 12 hours.

Direct products of these RUCs include those custom TAFs for the airlines but the data figures into products like Wintertyping. This is how the system decides if the mix shown on the radar image is rain, mixed or snow. By having a 3D model of the atmosphere and laying that over a 3D model of terrain, the system can pretty precisely guess what’s happening where the atmosphere and terrain meet. That’s why the rain/mix/snow you see at the FBO may be much more variegated than the wide bands of precip type you see on TV news.

WSI also runs something called the Weather Research and Forecasting model (WRF, pronounced “Worf”). This takes four times as long to run as the three-hour RUC (even on 80 high-end computers working in parallel), but it models the atmosphere with a four-km grid and looks 52 hours into the future.

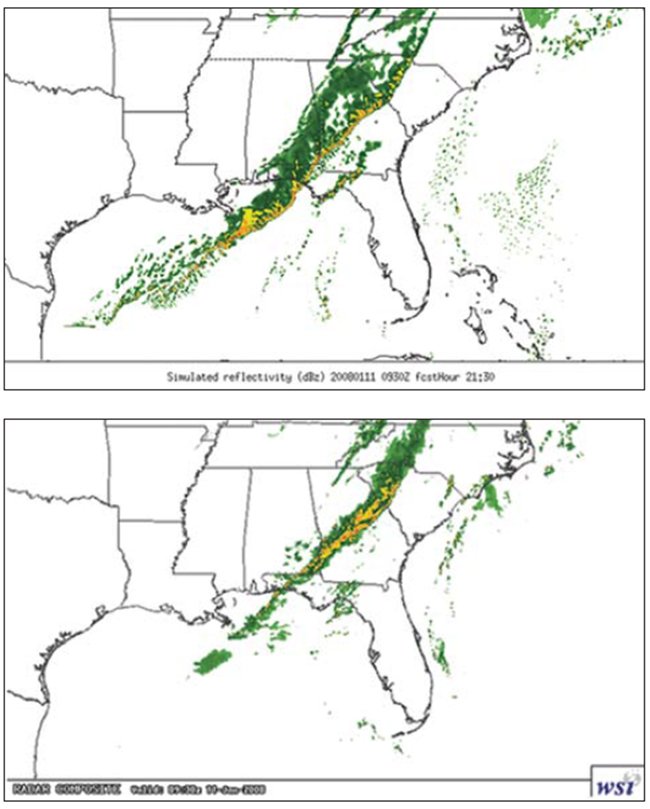

The WRF figures into a product that WSI doesn’t offer to pilots yet, but we hope they do in the future: forecast NEXRAD. WRF can predict where thunderstorm activity may be up to three days in advance and with the resolution the size of a small town. The government has been experimenting with this for years but has yet to offer it as a product (http://www.emc.ncep.noaa.gov/mmb/mpyle/spcprod/00/).

How good is it? Well, it’s not perfect but it’s more often right than wrong, at least at locating the areas where there will be storms. How would you like to have the ability to see that a line of storms are forecast to hit the airport the same time you do—the day after tomorrow? That might allow you to craft a plan B in the leisure of your living room rather than in a bouncing cockpit looking at a wall of black cloud.

Forecast NEXRAD won’t appear in the FBO any time soon, but we can always hope for the future while appreciating all the weather data we’ve got. Now we just need to find the FBO where they keep making fresh coffee.