When comparing a high-speed, cruise-power descent against a cruise-speed, reduced-power descent, there are a surprisingly large number of variables in the equation, all pulling in different directions.

On the one hand, descending at cruise power will guarantee a higher airspeed, but on the other hand it comes at the cost of a higher fuel burn. However, a higher airspeed will reduce the amount of time in the air, and thus overall fuel cost, right? What about true airspeed? True airspeeds are highest at cruise altitudes, and decrease approximately two-percent per thousand feet during the descent, which throws in an another dimension. So which method is truly more efficient?

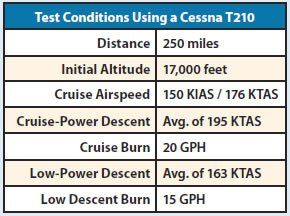

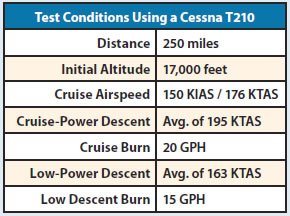

Not having an infinite amount of money to perform airborne testing, I developed a mathematical model to test out descent profiles over time, taking into consideration variables such as airspeed variation and fuel burn. While it’s not a completely perfect simulation, it should give a rough estimate of expected performance, at least enough for comparison.

Common sense wins when it comes to descent planning. Flying a cruise-power descent at a fairly shallow average rate of descent of around 300 FPM will give you the shortest flight time at the cost of a slightly higher fuel burn. A middling descent rate gives you some time savings at little fuel cost.

Running this with some other starting points, it turns out that if you start your descent below 8000 feet or fly an aircraft having a difference in airspeed between cruise-power descent and cruise-airspeed descents of 30 knots or less, any savings were basically negligible.

— L.S.